Mentioned in:

Most Anticipated: The Great Spring 2024 Preview

April

April 2

Women! In! Peril! by Jessie Ren Marshall [F]

For starters, excellent title. This debut short story collection from playwright Marshall spans sex bots and space colonists, wives and divorcées, prodding at the many meanings of womanhood. Short story master Deesha Philyaw, also taken by the book's title, calls this one "incisive! Provocative! And utterly satisfying!" —Sophia M. Stewart

The Audacity by Ryan Chapman [F]

This sophomore effort, after the darkly sublime absurdity of Riots I have Known, trades in the prison industrial complex for the Silicon Valley scam. Chapman has a sharp eye and a sharper wit, and a book billed as a "bracing satire about the implosion of a Theranos-like company, a collapsing marriage, and a billionaires’ 'philanthropy summit'" promises some good, hard laughs—however bitter they may be—at the expense of the über-rich. —John H. Maher

The Obscene Bird of Night by José Donoso, tr. Leonard Mades [F]

I first learned about this book from an essay in this publication by Zachary Issenberg, who alternatively calls it Donoso's "masterpiece," "a perfect novel," and "the crowning achievement of the gothic horror genre." He recommends going into the book without knowing too much, but describes it as "a story assembled from the gossip of society’s highs and lows, which revolves and blurs into a series of interlinked nightmares in which people lose their memory, their sex, or even their literal organs." —SMS

Globetrotting ed. Duncan Minshull [NF]

I'm a big walker, so I won't be able to resist this assemblage of 50 writers—including Edith Wharton, Katharine Mansfield, Helen Garner, and D.H. Lawrence—recounting their various journeys by foot, edited by Minshull, the noted walker-writer-anthologist behind The Vintage Book of Walking (2000) and Where My Feet Fall (2022). —SMS

All Things Are Too Small by Becca Rothfeld [NF]

Hieronymus Bosch, eat your heart out! The debut book from Rothfeld, nonfiction book critic at the Washington Post, celebrates our appetite for excess in all its material, erotic, and gluttonous glory. Covering such disparate subjects from decluttering to David Cronenberg, Rothfeld looks at the dire cultural—and personal—consequences that come with adopting a minimalist sensibility and denying ourselves pleasure. —Daniella Fishman

A Good Happy Girl by Marissa Higgins [F]

Higgins, a regular contributor here at The Millions, debuts with a novel of a young woman who is drawn into an intense and all-consuming emotional and sexual relationship with a married lesbian couple. Halle Butler heaps on the praise for this one: “Sometimes I could not believe how easily this book moved from gross-out sadism into genuine sympathy. Totally surprising, totally compelling. I loved it.” —SMS

City Limits by Megan Kimble [NF]

As a Los Angeleno who is steadily working my way through The Power Broker, this in-depth investigation into the nation's freeways really calls to me. (Did you know Robert Moses couldn't drive?) Kimble channels Caro by locating the human drama behind freeways and failures of urban planning. —SMS

We Loved It All by Lydia Millet [NF]

Planet Earth is a pretty awesome place to be a human, with its beaches and mountains, sunsets and birdsong, creatures great and small. Millet, a creative director at the Center for Biological Diversity in Tucson, infuses her novels with climate grief and cautions against extinction, and in this nonfiction meditation, she makes a case for a more harmonious coexistence between our species and everybody else in the natural world. If a nostalgic note of “Auld Lang Syne” trembles in Millet’s title, her personal anecdotes and public examples call for meaningful environmental action from local to global levels. —Nathalie op de Beeck

Like Love by Maggie Nelson [NF]

The new book from Nelson, one of the most towering public intellectuals alive today, collects 20 years of her work—including essays, profiles, and reviews—that cover disparate subjects, from Prince and Kara Walker to motherhood and queerness. For my fellow Bluets heads, this will be essential reading. —SMS

Traces of Enayat by Iman Mersal, tr. Robin Moger [NF]

Mersal, one of the preeminent poets of the Arabic-speaking world, recovers the life, work, and legacy of the late Egyptian writer Enayat al-Zayyat in this biographical detective story. Mapping the psyche of al-Zayyat, who died by suicide in 1963, alongside her own, Mersal blends literary mystery and memoir to produce a wholly original portrait of two women writers. —SMS

The Letters of Emily Dickinson ed. Cristanne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell [NF]

The letters of Emily Dickinson, one of the greatest and most beguiling of American poets, are collected here for the first time in nearly 60 years. Her correspondence not only gives access to her inner life and social world, but reveal her to be quite the prose stylist. "In these letters," says Jericho Brown, "we see the life of a genius unfold." Essential reading for any Dickinson fan. —SMS

April 9

Short War by Lily Meyer [F]

The debut novel from Meyer, a critic and translator, reckons with the United States' political intervention in South America through the stories of two generations: a young couple who meet in 1970s Santiago, and their American-born child spending a semester Buenos Aires. Meyer is a sharp writer and thinker, and a great translator from the Spanish; I'm looking forward to her fiction debut. —SMS

There's Going to Be Trouble by Jen Silverman [F]

Silverman's third novel spins a tale of an American woman named Minnow who is drawn into a love affair with a radical French activist—a romance that, unbeknown to her, mirrors a relationship her own draft-dodging father had against the backdrop of the student movements of the 1960s. Teasing out the intersections of passion and politics, There's Going to Be Trouble is "juicy and spirited" and "crackling with excitement," per Jami Attenberg. —SMS

Table for One by Yun Ko-eun, tr. Lizzie Buehler [F]

I thoroughly enjoyed Yun Ko-eun's 2020 eco-thriller The Disaster Tourist, also translated by Buehler, so I'm excited for her new story collection, which promises her characteristic blend of mundanity and surrealism, all in the name of probing—and poking fun—at the isolation and inanity of modern urban life. —SMS

Playboy by Constance Debré, tr. Holly James [NF]

The prequel to the much-lauded Love Me Tender, and the first volume in Debré's autobiographical trilogy, Playboy's incisive vignettes explore the author's decision to abandon her marriage and career and pursue the precarious life of a writer, which she once told Chris Kraus was "a bit like Saint Augustine and his conversion." Virginie Despentes is a fan, so I'll be checking this out. —SMS

Native Nations by Kathleen DuVal [NF]

DuVal's sweeping history of Indigenous North America spans a millennium, beginning with the ancient cities that once covered the continent and ending with Native Americans' continued fight for sovereignty. A study of power, violence, and self-governance, Native Nations is an exciting contribution to a new canon of North American history from an Indigenous perspective, perfect for fans of Ned Blackhawk's The Rediscovery of America. —SMS

Personal Score by Ellen van Neerven [NF]

I’ve always been interested in books that drill down on a specific topic in such a way that we also learn something unexpected about the world around us. Australian writer Van Neerven's sports memoir is so much more than that, as they explore the relationship between sports and race, gender, and sexuality—as well as the paradox of playing a colonialist sport on Indigenous lands. Two Dollar Radio, which is renowned for its edgy list, is publishing this book, so I know it’s going to blow my mind. —Claire Kirch

April 16

The Notebooks of Sonny Rollins by Sonny Rollins [NF]

The musings, recollections, and drawings of jazz legend Sonny Rollins are collected in this compilation of his precious notebooks, which he began keeping in 1959, the start of what would become known as his “Bridge Years,” during which he would practice at all hours on the Williamsburg Bridge. Rollins chronicles everything from his daily routine to reflections on music theory and the philosophical underpinnings of his artistry. An indispensable look into the mind and interior life of one of the most celebrated jazz musicians of all time. —DF

Henry Henry by Allen Bratton [F]

Bratton’s ambitious debut reboots Shakespeare’s Henriad, landing Hal Lancaster, who’s in line to be the 17th Duke of Lancaster, in the alcohol-fueled queer party scene of 2014 London. Hal’s identity as a gay man complicates his aristocratic lineage, and his dalliances with over-the-hill actor Jack Falstaff and promising romance with one Harry Percy, who shares a name with history’s Hotspur, will have English majors keeping score. Don’t expect a rom-com, though. Hal’s fraught relationship with his sexually abusive father, and the fates of two previous gay men from the House of Lancaster, lend gravity to this Bard-inspired take. —NodB

Bitter Water Opera by Nicolette Polek [F]

Graywolf always publishes books that make me gasp in awe and this debut novel, by the author of the entrancing 2020 story collection Imaginary Museums, sounds like it’s going to keep me awake at night as well. It’s a tale about a young woman who’s lost her way and writes a letter to a long-dead ballet dancer—who then visits her, and sets off a string of strange occurrences. —CK

Norma by Sarah Mintz [F]

Mintz's debut novel follows the titular widow as she enjoys her newfound freedom by diving headfirst into her surrounds, both IRL and online. Justin Taylor says, "Three days ago I didn’t know Sarah Mintz existed; now I want to know where the hell she’s been all my reading life. (Canada, apparently.)" —SMS

What Kingdom by Fine Gråbøl, tr. Martin Aitken [F]

A woman in a psychiatric ward dreams of "furniture flickering to life," a "chair that greets you," a "bookshelf that can be thrown on like an apron." This sounds like the moving answer to the otherwise puzzling question, "What if the Kantian concept of ding an sich were a novel?" —JHM

Weird Black Girls by Elwin Cotman [F]

Cotman, the author of three prior collections of speculative short stories, mines the anxieties of Black life across these seven tales, each of them packed with pop culture references and supernatural conceits. Kelly Link calls Cotman's writing "a tonic to ward off drabness and despair." —SMS

Presence by Tracy Cochran [NF]

Last year marked my first earnest attempt at learning to live more mindfully in my day-to-day, so I was thrilled when this book serendipitously found its way into my hands. Cochran, a New York-based meditation teacher and Tibetan Buddhist practitioner of 50 years, delivers 20 psycho-biographical chapters on recognizing the importance of the present, no matter how mundane, frustrating, or fortuitous—because ultimately, she says, the present is all we have. —DF

Committed by Suzanne Scanlon [NF]

Scanlon's memoir uses her own experience of mental illness to explore the enduring trope of the "madwoman," mining the work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Audre Lorde, and others for insights into the long literary tradition of women in psychological distress. The blurbers for this one immediately caught my eye, among them Natasha Trethewey, Amina Cain, and Clancy Martin, who compares Scanlon's work here to that of Marguerite Duras. —SMS

Unrooted by Erin Zimmerman [NF]

This science memoir explores Zimmerman's journey to botany, a now endangered field. Interwoven with Zimmerman's experiences as a student and a mother is an impassioned argument for botany's continued relevance and importance against the backdrop of climate change—a perfect read for gardeners, plant lovers, or anyone with an affinity for the natural world. —SMS

April 23

Reboot by Justin Taylor [F]

Extremely online novels, as a rule, have become tiresome. But Taylor has long had a keen eye for subcultural quirks, so it's no surprise that PW's Alan Scherstuhl says that "reading it actually feels like tapping into the internet’s best celeb gossip, fiercest fandom outrages, and wildest conspiratorial rabbit holes." If that's not a recommendation for the Book Twitter–brained reader in you, what is? —JHM

Divided Island by Daniela Tarazona, tr. Lizzie Davis and Kevin Gerry Dunn [F]

A story of multiple personalities and grief in fragments would be an easy sell even without this nod from Álvaro Enrigue: "I don't think that there is now, in Mexico, a literary mind more original than Daniela Tarazona's." More original than Mario Bellatin, or Cristina Rivera Garza? This we've gotta see. —JHM

Prairie, Dresses, Art, Other by Danielle Dutton [NF]

Coffee House Press has for years relished its reputation for publishing “experimental” literature, and this collection of short stories and essays about literature and art and the strangeness of our world is right up there with the rest of Coffee House’s edgiest releases. Don’t be fooled by the simple cover art—Dutton’s work is always formally inventive, refreshingly ambitious, and totally brilliant. —CK

I Just Keep Talking by Nell Irvin Painter [NF]

I first encountered Nell Irvin Painter in graduate school, as I hung out with some Americanists who were her students. Painter was always a dazzling, larger-than-life figure, who just exuded power and brilliance. I am so excited to read this collection of her essays on history, literature, and politics, and how they all intersect. The fact that this collection contains Painter’s artwork is a big bonus. —CK

April 30

Real Americans by Rachel Khong [F]

The latest novel from Khong, the author of Goodbye, Vitamin, explores class dynamics and the illusory American Dream across generations. It starts out with a love affair between an impoverished Chinese American woman from an immigrant family and an East Coast elite from a wealthy family, before moving us along 21 years: 15-year-old Nick knows that his single mother is hiding something that has to do with his biological father and thus, his identity. C Pam Zhang deems this "a book of rare charm," and Andrew Sean Greer calls it "gorgeous, heartfelt, soaring, philosophical and deft." —CK

The Swans of Harlem by Karen Valby [NF]

Huge thanks to Bebe Neuwirth for putting this book on my radar (she calls it "fantastic") with additional gratitude to Margo Jefferson for sealing the deal (she calls it "riveting"). Valby's group biography of five Black ballerinas who forever transformed the art form at the height of the Civil Rights movement uncovers the rich and hidden history of Black ballet, spotlighting the trailblazers who paved the way for the Misty Copelands of the world. —SMS

Appreciation Post by Tara Ward [NF]

Art historian Ward writes toward an art history of Instagram in Appreciation Post, which posits that the app has profoundly shifted our long-established ways of interacting with images. Packed with cultural critique and close reading, the book synthesizes art history, gender studies, and media studies to illuminate the outsize role that images play in all of our lives. —SMS

May

May 7

Bad Seed by Gabriel Carle, tr. Heather Houde [F]

Carle’s English-language debut contains echoes of Denis Johnson’s Jesus’s Son and Mariana Enriquez’s gritty short fiction. This story collection haunting but cheeky, grim but hopeful: a student with HIV tries to avoid temptation while working at a bathhouse; an inebriated friend group witnesses San Juan go up in literal flames; a sexually unfulfilled teen drowns out their impulses by binging TV shows. Puerto Rican writer Luis Negrón calls this “an extraordinary literary debut.” —Liv Albright

The Lady Waiting by Magdalena Zyzak [F]

Zyzak’s sophomore novel is a nail-biting delight. When Viva, a young Polish émigré, has a chance encounter with an enigmatic gallerist named Bobby, Viva’s life takes a cinematic turn. Turns out, Bobby and her husband have a hidden agenda—they plan to steal a Vermeer, with Viva as their accomplice. Further complicating things is the inevitable love triangle that develops among them. Victor LaValle calls this “a superb accomplishment," and Percival Everett says, "This novel pops—cosmopolitan, sexy, and funny." —LA

América del Norte by Nicolás Medina Mora [F]

Pitched as a novel that "blends the Latin American traditions of Roberto Bolaño and Fernanda Melchor with the autofiction of U.S. writers like Ben Lerner and Teju Cole," Mora's debut follows a young member of the Mexican elite as he wrestles with questions of race, politics, geography, and immigration. n+1 co-editor Marco Roth calls Mora "the voice of the NAFTA generation, and much more." —SMS

How It Works Out by Myriam Lacroix [F]

LaCroix's debut novel is the latest in a strong early slate of novels for the Overlook Press in 2024, and follows a lesbian couple as their relationship falls to pieces across a number of possible realities. The increasingly fascinating and troubling potentialities—B-list feminist celebrity, toxic employer-employee tryst, adopting a street urchin, cannibalism as relationship cure—form a compelling image of a complex relationship in multiversal hypotheticals. —JHM

Cinema Love by Jiaming Tang [F]

Ting's debut novel, which spans two continents and three timelines, follows two gay men in rural China—and, later, New York City's Chinatown—who frequent the Workers' Cinema, a movie theater where queer men cruise for love. Robert Jones, Jr. praises this one as "the unforgettable work of a patient master," and Jessamine Chan calls it "not just an extraordinary debut, but a future classic." —SMS

First Love by Lilly Dancyger [NF]

Dancyger's essay collection explores the platonic romances that bloom between female friends, giving those bonds the love-story treatment they deserve. Centering each essay around a formative female friendship, and drawing on everything from Anaïs Nin and Sylvia Plath to the "sad girls" of Tumblr, Dancyger probes the myriad meanings and iterations of friendship, love, and womanhood. —SMS

See Loss See Also Love by Yukiko Tominaga [F]

In this impassioned debut, we follow Kyoko, freshly widowed and left to raise her son alone. Through four vignettes, Kyoko must decide how to raise her multiracial son, whether to remarry or stay husbandless, and how to deal with life in the face of loss. Weike Wang describes this one as “imbued with a wealth of wisdom, exploring the languages of love and family.” —DF

The Novices of Lerna by Ángel Bonomini, tr. Jordan Landsman [F]

The Novices of Lerna is Landsman's translation debut, and what a way to start out: with a work by an Argentine writer in the tradition of Jorge Luis Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares whose work has never been translated into English. Judging by the opening of this short story, also translated by Landsman, Bonomini's novel of a mysterious fellowship at a Swiss university populated by doppelgängers of the protagonist is unlikely to disappoint. —JHM

Black Meme by Legacy Russell [NF]

Russell, best known for her hit manifesto Glitch Feminism, maps Black visual culture in her latest. Black Meme traces the history of Black imagery from 1900 to the present, from the photograph of Emmett Till published in JET magazine to the footage of Rodney King's beating at the hands of the LAPD, which Russell calls the first viral video. Per Margo Jefferson, "You will be galvanized by Legacy Russell’s analytic brilliance and visceral eloquence." —SMS

The Eighth Moon by Jennifer Kabat [NF]

Kabat's debut memoir unearths the history of the small Catskills town to which she relocated in 2005. The site of a 19th-century rural populist uprising, and now home to a colorful cast of characters, the Appalachian community becomes a lens through which Kabat explores political, economic, and ecological issues, mining the archives and the work of such writers as Adrienne Rich and Elizabeth Hardwick along the way. —SMS

Stories from the Center of the World ed. Jordan Elgrably [F]

Many in America hold onto broad, centuries-old misunderstandings of Arab and Muslim life and politics that continue to harm, through both policy and rhetoric, a perpetually embattled and endangered region. With luck, these 25 tales by writers of Middle Eastern and North African origin might open hearts and minds alike. —JHM

An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children by Jamaica Kincaid and Kara Walker [NF]

Two of the most brilliant minds on the planet—writer Jamaica Kincaid and visual artist Kara Walker—have teamed up! On a book! About plants! A dream come true. Details on this slim volume are scant—see for yourself—but I'm counting down the minutes till I can read it all the same. —SMS

Physics of Sorrow by Georgi Gospodinov, tr. Angela Rodel [F]

I'll be honest: I would pick up this book—by the International Booker Prize–winning author of Time Shelter—for the title alone. But also, the book is billed as a deeply personal meditation on both Communist Bulgaria and Greek myth, so—yep, still picking this one up. —JHM

May 14

This Strange Eventful History by Claire Messud [F]

I read an ARC of this enthralling fictionalization of Messud’s family history—people wandering the world during much of the 20th century, moving from Algeria to France to North America— and it is quite the story, with a postscript that will smack you on the side of the head and make you re-think everything you just read. I can't recommend this enough. —CK

Woodworm by Layla Martinez, tr. Sophie Hughes and Annie McDermott [F]

Martinez’s debut novel takes cabin fever to the max in this story of a grandmother, granddaughter, and their haunted house, set against the backdrop of the Spanish Civil War. As the story unfolds, so do the house’s secrets, the two women must learn to collaborate with the malevolent spirits living among them. Mariana Enriquez says that this "tense, chilling novel tells a story of specters, class war, violence, and loneliness, as naturally as if the witches had dictated this lucid, terrible nightmare to Martínez themselves.” —LA

Self Esteem and the End of the World by Luke Healy [NF]

Ah, writers writing about writing. A tale as old as time, and often timeworn to boot. But graphic novelists graphically noveling about graphic novels? (Verbing weirds language.) It still feels fresh to me! Enter Healy's tale of "two decades of tragicomic self-discovery" following a protagonist "two years post publication of his latest book" and "grappling with his identity as the world crumbles." —JHM

All Fours by Miranda July [F]

In excruciating, hilarious detail, All Fours voices the ethically dubious thoughts and deeds of an unnamed 45-year-old artist who’s worried about aging and her capacity for desire. After setting off on a two-week round-trip drive from Los Angeles to New York City, the narrator impulsively checks into a motel 30 miles from her home and only pretends to be traveling. Her flagrant lies, unapologetic indolence, and semi-consummated seduction of a rent-a-car employee set the stage for a liberatory inquisition of heteronorms and queerness. July taps into the perimenopause zeitgeist that animates Jen Beagin’s Big Swiss and Melissa Broder’s Death Valley. —NodB

Love Junkie by Robert Plunket [F]

When a picture-perfect suburban housewife's life is turned upside down, a chance brush with New York City's gay scene launches her into gainful, albeit unconventional, employment. Set at the dawn of the AIDs epidemic, Mimi Smithers, described as a "modern-day Madame Bovary," goes from planning parties in Westchester to selling used underwear with a Manhattan porn star. As beloved as it is controversial, Plunket's 1992 cult novel will get a much-deserved second life thanks to this reissue by New Directions. (Maybe this will finally galvanize Madonna, who once optioned the film rights, to finally make that movie.) —DF

Tomorrowing by Terry Bisson [F]

The newest volume in Duke University’s Practices series collects for the first time the late Terry Bisson’s Locus column "This Month in History," which ran for two decades. In it, the iconic "They’re Made Out of Meat" author weaves an alt-history of a world almost parallel to ours, featuring AI presidents, moon mountain hikes, a 196-year-old Walt Disney’s resurrection, and a space pooch on Mars. This one promises to be a pure spectacle of speculative fiction. —DF

Chop Fry Watch Learn by Michelle T. King [NF]

A large portion of the American populace still confuses Chinese American food with Chinese food. What a delight, then, to discover this culinary history of the worldwide dissemination of that great cuisine—which moonlights as a biography of Chinese cookbook and TV cooking program pioneer Fu Pei-mei. —JHM

On the Couch ed. Andrew Blauner [NF]

André Aciman, Susie Boyt, Siri Hustvedt, Rivka Galchen, and Colm Tóibín are among the 25 literary luminaries to contribute essays on Freud and his complicated legacy to this lively volume, edited by writer, editor, and literary agent Blauner. Taking tacts both personal and psychoanalytical, these essays paint a fresh, full picture of Freud's life, work, and indelible cultural impact. —SMS

Another Word for Love by Carvell Wallace [NF]

Wallace is one of the best journalists (and tweeters) working today, so I'm really looking forward to his debut memoir, which chronicles growing up Black and queer in America, and navigating the world through adulthood. One of the best writers working today, Kiese Laymon, calls Another Word for Love as “One of the most soulfully crafted memoirs I’ve ever read. I couldn’t figure out how Carvell Wallace blurred time, region, care, and sexuality into something so different from anything I’ve read before." —SMS

The Devil's Best Trick by Randall Sullivan [NF]

A cultural history interspersed with memoir and reportage, Sullivan's latest explores our ever-changing understandings of evil and the devil, from Egyptian gods and the Book of Job to the Salem witch trials and Black Mass ceremonies. Mining the work of everyone from Zoraster, Plato, and John Milton to Edgar Allen Poe, Aleister Crowley, and Charles Baudelaire, this sweeping book chronicles evil and the devil in their many forms. --SMS

The Book Against Death by Elias Canetti, tr. Peter Filkins [NF]

In this newly-translated collection, Nobel laureate Canetti, who once called himself death's "mortal enemy," muses on all that death inevitably touches—from the smallest ant to the Greek gods—and condemns death as a byproduct of war and despots' willingness to use death as a pathway to power. By means of this book's very publication, Canetti somewhat succeeds in staving off death himself, ensuring that his words live on forever. —DF

Rise of a Killah by Ghostface Killah [NF]

"Why is the sky blue? Why is water wet? Why did Judas rat to the Romans while Jesus slept?" Ghostface Killah has always asked the big questions. Here's another one: Who needs to read a blurb on a literary site to convince them to read Ghost's memoir? —JHM

May 21

Exhibit by R.O. Kwon [F]

It's been six years since Kwon's debut, The Incendiaries, hit shelves, and based on that book's flinty prose alone, her latest would be worth a read. But it's also a tale of awakening—of its protagonist's latent queerness, and of the "unquiet spirit of an ancestor," that the author herself calls so "shot through with physical longing, queer lust, and kink" that she hopes her parents will never read it. Tantalizing enough for you? —JHM

Cecilia by K-Ming Chang [F]

Chang, the author of Bestiary, Gods of Want, and Organ Meats, returns with this provocative and oft-surreal novella. While the story is about two childhood friends who became estranged after a bizarre sexual encounter but re-connect a decade later, it’s also an exploration of how the human body and its excretions can be both pleasurable and disgusting. —CK

The Great State of West Florida by Kent Wascom [F]

The Great State of West Florida is Wascom's latest gothicomic novel set on Florida's apocalyptic coast. A gritty, ominous book filled with doomed Floridians, the passages fly by with sentences that delight in propulsive excess. In the vein of Thomas McGuane's early novels or Brian De Palma's heyday, this stylized, savory, and witty novel wields pulp with care until it blooms into a new strain of American gothic. —Zachary Issenberg

Cartoons by Kit Schluter [F]

Bursting with Kafkaesque absurdism and a hearty dab of abstraction, Schluter’s Cartoons is an animated vignette of life's minutae. From the ravings of an existential microwave to a pencil that is afraid of paper, Schluter’s episodic outré oozes with animism and uncanniness. A grand addition to City Light’s repertoire, it will serve as a zany reminder of the lengths to which great fiction can stretch. —DF

May 28

Lost Writings by Mina Loy, ed. Karla Kelsey [F]

In the early 20th century, avant-garde author, visual artist, and gallerist Mina Loy (1882–1966) led an astonishing creative life amid European and American modernist circles; she satirized Futurists, participated in Surrealist performance art, and created paintings and assemblages in addition to writing about her experiences in male-dominated fields of artistic practice. Diligent feminist scholars and art historians have long insisted on her cultural significance, yet the first Loy retrospective wasn’t until 2023. Now Karla Kelsey, a poet and essayist, unveils two never-before-published, autobiographical midcentury manuscripts by Loy, The Child and the Parent and Islands in the Air, written from the 1930s to the 1950s. It's never a bad time to be re-rediscovered. —NodB

I'm a Fool to Want You by Camila Sosa Villada, tr. Kit Maude [F]

Villada, whose debut novel Bad Girls, also translated by Maude, captured the travesti experience in Argentina, returns with a short story collection that runs the genre gamut from gritty realism and social satire to science fiction and fantasy. The throughline is Villada's boundless imagination, whether she's conjuring the chaos of the Mexican Inquisition or a trans sex worker befriending a down-and-out Billie Holiday. Angie Cruz calls this "one of my favorite short-story collections of all time." —SMS

The Editor by Sara B. Franklin [NF]

Franklin's tenderly written and meticulously researched biography of Judith Jones—the legendary Knopf editor who worked with such authors as John Updike, Sylvia Plath, Elizabeth Bowen, Anne Tyler, and, perhaps most consequentially, Julia Child—was largely inspired by Franklin's own friendship with Jones in the final years of her life, and draws on a rich trove of interviews and archives. The Editor retrieves Jones from the margins of publishing history and affirms her essential role in shaping the postwar cultural landscape, from fiction to cooking and beyond. —SMS

The Book-Makers by Adam Smyth [NF]

A history of the book told through 18 microbiographies of particularly noteworthy historical personages who made them? If that's not enough to convince you, consider this: the small press is represented here by Nancy Cunard, the punchy and enormously influential founder of Hours Press who romanced both Aldous Huxley and Ezra Pound, knew Hemingway and Joyce and Langston Hughes and William Carlos Williams, and has her own MI5 file. Also, the subject of the binding chapter is named "William Wildgoose." —JHM

June

June 4

The Future Was Color by Patrick Nathan [F]

A gay Hungarian immigrant writing crappy monster movies in the McCarthy-era Hollywood studio system gets swept up by a famous actress and brought to her estate in Malibu to write what he really cares about—and realizes he can never escape his traumatic past. Sunset Boulevard is shaking. —JHM

A Cage Went in Search of a Bird [F]

This collection brings together a who's who of literary writers—10 of them, to be precise— to write Kafka fanfiction, from Joshua Cohen to Yiyun Li. Then it throws in weirdo screenwriting dynamo Charlie Kaufman, for good measure. A boon for Kafkaheads everywhere. —JHM

We Refuse by Kellie Carter Jackson [NF]

Jackson, a historian and professor at Wellesley College, explores the past and present of Black resistance to white supremacy, from work stoppages to armed revolt. Paying special attention to acts of resistance by Black women, Jackson attempts to correct the historical record while plotting a path forward. Jelani Cobb describes this "insurgent history" as "unsparing, erudite, and incisive." —SMS

Holding It Together by Jessica Calarco [NF]

Sociologist Calarco's latest considers how, in lieu of social safety nets, the U.S. has long relied on women's labor, particularly as caregivers, to hold society together. Calarco argues that while other affluent nations cover the costs of care work and direct significant resources toward welfare programs, American women continue to bear the brunt of the unpaid domestic labor that keeps the nation afloat. Anne Helen Petersen calls this "a punch in the gut and a call to action." —SMS

Miss May Does Not Exist by Carrie Courogen [NF]

A biography of Elaine May—what more is there to say? I cannot wait to read this chronicle of May's life, work, and genius by one of my favorite writers and tweeters. Claire Dederer calls this "the biography Elaine May deserves"—which is to say, as brilliant as she was. —SMS

Fire Exit by Morgan Talty [F]

Talty, whose gritty story collection Night of the Living Rez was garlanded with awards, weighs the concept of blood quantum—a measure that federally recognized tribes often use to determine Indigenous membership—in his debut novel. Although Talty is a citizen of the Penobscot Indian Nation, his narrator is on the outside looking in, a working-class white man named Charles who grew up on Maine’s Penobscot Reservation with a Native stepfather and friends. Now Charles, across the river from the reservation and separated from his biological daughter, who lives there, ponders his exclusion in a novel that stokes controversy around the terms of belonging. —NodB

June 11

The Material by Camille Bordas [F]

My high school English teacher, a somewhat dowdy but slyly comical religious brother, had a saying about teaching high school students: "They don't remember the material, but they remember the shtick." Leave it to a well-named novel about stand-up comedy (by the French author of How to Behave in a Crowd) to make you remember both. --SMS

Ask Me Again by Clare Sestanovich [F]

Sestanovich follows up her debut story collection, Objects of Desire, with a novel exploring a complicated friendship over the years. While Eva and Jamie are seemingly opposites—she's a reserved South Brooklynite, while he's a brash Upper Manhattanite—they bond over their innate curiosity. Their paths ultimately diverge when Eva settles into a conventional career as Jamie channels his rebelliousness into politics. Ask Me Again speaks to anyone who has ever wondered whether going against the grain is in itself a matter of privilege. Jenny Offill calls this "a beautifully observed and deeply philosophical novel, which surprises and delights at every turn." —LA

Disordered Attention by Claire Bishop [NF]

Across four essays, art historian and critic Bishop diagnoses how digital technology and the attention economy have changed the way we look at art and performance today, identifying trends across the last three decades. A perfect read for fans of Anna Kornbluh's Immediacy, or the Style of Too Late Capitalism (also from Verso).

War by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, tr. Charlotte Mandell [F]

For years, literary scholars mourned the lost manuscripts of Céline, the acclaimed and reviled French author whose work was stolen from his Paris apartment after he fled to Germany in 1944, fearing punishment for his collaboration with the Nazis. But, with the recent discovery of those fabled manuscripts, War is now seeing the light of day thanks to New Directions (for anglophone readers, at least—the French have enjoyed this one since 2022 courtesy of Gallimard). Adam Gopnik writes of War, "A more intense realization of the horrors of the Great War has never been written." —DF

The Uptown Local by Cory Leadbeater [NF]

In his debut memoir, Leadbeater revisits the decade he spent working as Joan Didion's personal assistant. While he enjoyed the benefits of working with Didion—her friendship and mentorship, the more glamorous appointments on her social calendar—he was also struggling with depression, addiction, and profound loss. Leadbeater chronicles it all in what Chloé Cooper Jones calls "a beautiful catalog of twin yearnings: to be seen and to disappear; to belong everywhere and nowhere; to go forth and to return home, and—above all else—to love and to be loved." —SMS

Out of the Sierra by Victoria Blanco [NF]

Blanco weaves storytelling with old-fashioned investigative journalism to spotlight the endurance of Mexico's Rarámuri people, one of the largest Indigenous tribes in North America, in the face of environmental disasters, poverty, and the attempts to erase their language and culture. This is an important book for our times, dealing with pressing issues such as colonialism, migration, climate change, and the broken justice system. —CK

Any Person Is the Only Self by Elisa Gabbert [NF]

Gabbert is one of my favorite living writers, whether she's deconstructing a poem or tweeting about Seinfeld. Her essays are what I love most, and her newest collection—following 2020's The Unreality of Memory—sees Gabbert in rare form: witty and insightful, clear-eyed and candid. I adored these essays, and I hope (the inevitable success of) this book might augur something an essay-collection renaissance. (Seriously! Publishers! Where are the essay collections!) —SMS

Tehrangeles by Porochista Khakpour [F]

Khakpour's wit has always been keen, and it's hard to imagine a writer better positioned to take the concept of Shahs of Sunset and make it literary. "Like Little Women on an ayahuasca trip," says Kevin Kwan, "Tehrangeles is delightfully twisted and heartfelt." —JHM

Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell by Ann Powers [NF]

The moment I saw this book's title—which comes from the opening (and, as it happens, my favorite) track on Mitchell's 1971 masterpiece Blue—I knew it would be one of my favorite reads of the year. Powers, one of the very best music critics we've got, masterfully guides readers through Mitchell's life and work at a fascinating slant, her approach both sweeping and intimate as she occupies the dual roles of biographer and fan. —SMS

All Desire Is a Desire for Being by René Girard, ed. Cynthia L. Haven [NF]

I'll be honest—the title alone stirs something primal in me. In honor of Girard's centennial, Penguin Classics is releasing a smartly curated collection of his most poignant—and timely—essays, touching on everything from violence to religion to the nature of desire. Comprising essays selected by the scholar and literary critic Cynthia L. Haven, who is also the author of the first-ever biographical study of Girard, Evolution of Desire, this book is "essential reading for Girard devotees and a perfect entrée for newcomers," per Maria Stepanova. —DF

June 18

Craft by Ananda Lima [F]

Can you imagine a situation in which interconnected stories about a writer who sleeps with the devil at a Halloween party and can't shake him over the following decades wouldn't compel? Also, in one of the stories, New York City’s Penn Station is an analogue for hell, which is both funny and accurate. —JHM

Parade by Rachel Cusk [F]

Rachel Cusk has a new novel, her first in three years—the anticipation is self-explanatory. —SMS

Little Rot by Akwaeke Emezi [F]

Multimedia polymath and gender-norm disrupter Emezi, who just dropped an Afropop EP under the name Akwaeke, examines taboo and trauma in their creative work. This literary thriller opens with an upscale sex party and escalating violence, and although pre-pub descriptions leave much to the imagination (promising “the elite underbelly of a Nigerian city” and “a tangled web of sex and lies and corruption”), Emezi can be counted upon for an ambience of dread and a feverish momentum. —NodB

When the Clock Broke by John Ganz [NF]

I was having a conversation with multiple brilliant, thoughtful friends the other day, and none of them remembered the year during which the Battle of Waterloo took place. Which is to say that, as a rule, we should all learn our history better. So it behooves us now to listen to John Ganz when he tells us that all the wackadoodle fascist right-wing nonsense we can't seem to shake from our political system has been kicking around since at least the early 1990s. —JHM

Night Flyer by Tiya Miles [NF]

Miles is one of our greatest living historians and a beautiful writer to boot, as evidenced by her National Book Award–winning book All That She Carried. Her latest is a reckoning with the life and legend of Harriet Tubman, which Miles herself describes as an "impressionistic biography." As in all her work, Miles fleshes out the complexity, humanity, and social and emotional world of her subject. Tubman biographer Catherine Clinton says Miles "continues to captivate readers with her luminous prose, her riveting attention to detail, and her continuing genius to bring the past to life." —SMS

God Bless You, Otis Spunkmeyer by Joseph Earl Thomas [F]

Thomas's debut novel comes just two years after a powerful memoir of growing up Black, gay, nerdy, and in poverty in 1990s Philadelphia. Here, he returns to themes and settings that in that book, Sink, proved devastating, and throws post-service military trauma into the mix. —JHM

June 25

The Garden Against Time by Olivia Laing [NF]

I've been a fan of Laing's since The Lonely City, a formative read for a much-younger me (and I'd suspect for many Millions readers), so I'm looking forward to her latest, an inquiry into paradise refracted through the experience of restoring an 18th-century garden at her home the English countryside. As always, her life becomes a springboard for exploring big, thorny ideas (no pun intended)—in this case, the possibilities of gardens and what it means to make paradise on earth. —SMS

Cue the Sun! by Emily Nussbaum [NF]

Emily Nussbaum is pretty much the reason I started writing. Her 2019 collection of television criticism, I Like to Watch, was something of a Bible for college-aged me (and, in fact, was the first book I ever reviewed), and I've been anxiously awaiting her next book ever since. It's finally arrived, in the form of an utterly devourable cultural history of reality TV. Samantha Irby says, "Only Emily Nussbaum could get me to read, and love, a book about reality TV rather than just watching it," and David Grann remarks, "It’s rare for a book to feel alive, but this one does." —SMS

Woman of Interest by Tracy O'Neill [NF]

O’Neill's first work of nonfiction—an intimate memoir written with the narrative propulsion of a detective novel—finds her on the hunt for her biological mother, who she worries might be dying somewhere in South Korea. As she uncovers the truth about her enigmatic mother with the help of a private investigator, her journey increasingly becomes one of self-discovery. Chloé Cooper Jones writes that Woman of Interest “solidifies her status as one of our greatest living prose stylists.” —LA

Dancing on My Own by Simon Wu [NF]

New Yorkers reading this list may have witnessed Wu's artful curation at the Brooklyn Museum, or the Whitney, or the Museum of Modern Art. It makes one wonder how much he curated the order of these excellent, wide-ranging essays, which meld art criticism, personal narrative, and travel writing—and count Cathy Park Hong and Claudia Rankine as fans. —JHM

[millions_email]

Most Anticipated: The Great 2016 Book Preview

We think it's safe to say last year was a big year for the book world. In addition to new titles by Harper Lee, Jonathan Franzen, and Lauren Groff, we got novels by Ottessa Moshfegh, Claire Vaye Watkins, and our own Garth Risk Hallberg. At this early stage, it already seems evident this year will keep up the pace. There's a new Elizabeth Strout book, for one, and a new Annie Proulx; new novels by Don DeLillo, Curtis Sittenfeld, Richard Russo and Yann Martel; and much-hyped debut novels by Cynthia D'Aprix Sweeney and Callan Wink. There's also a new book by Alexander Chee, and a new translation of Nobel Prize-winner Herta Müller. The books previewed here are all fiction. Our nonfiction preview is available here.

While there's no such thing as a list that has everything, we feel certain this preview -- at 8,600 words and 93 titles -- is the only 2016 book preview you'll need. Scroll down to get started.

January:

My Name Is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout: The latest novel from the Pulitzer Prize-winning author of Olive Kitteridge centers on a mother and daughter’s tumultuous relationship. In a starred review, Kirkus reports: “The eponymous narrator looks back to the mid-1980s, when she goes into the hospital for an appendix removal and succumbs to a mysterious fever that keeps her there for nine weeks. The possible threat to her life brings Lucy’s mother, from whom she has been estranged for years, to her bedside -- but not the father whose World War II–related trauma is largely responsible for clever Lucy’s fleeing her impoverished family for college and life as a writer.” Publishers Weekly says this “masterly” novel’s central message “is that sometimes in order to express love, one has to forgive.” Let's hope HBO makes this one into a mini-series as well. (Edan)

The Past by Tessa Hadley: Hadley was described by one critic as “literary fiction’s best kept secret,” and Hilary Mantel has said she is “one of those writers a reader trusts,” which, considering the source, is as resounding an endorsement as one can possibly imagine. The English novelist is the author of five novels and two short story collections; in The Past, her sixth novel, siblings reunite to sell their grandparents’ old house. Most likely unsurprising to anyone who’s reunited with family for this sort of thing, “under the idyllic surface, there are tensions.” (Elizabeth)

Good on Paper by Rachel Cantor: Following her time-traveling debut, A Highly Unlikely Scenario, or a Neetsa Pizza Employee’s Guide to Saving the World (which is a member of The Millions Hall of Fame), Cantor’s second novel, Good on Paper, chronicles the story of academic and mother Shira Greene. After Shira abandons her PhD thesis on Dante Alighieri’s Vita Nuova, she takes an unfulfilling temp job. When Nobel Prize-winner Romei contacts her to translate his latest work based on Dante’s text, she couldn’t be more excited. But upon receiving his text, she fears “the work is not only untranslatable but designed to break her.” (Cara)

The Happy Marriage by Tahar Ben Jelloun: The latest novel by Morocco's most acclaimed living writer focuses on the dissolution of a marriage between a renowned painter and his wife. Using two distinct points of view, Ben Jelloun lets each of his characters -- man and wife -- tell their side of the story. Set against the backdrop of Casablanca in the midst of an awakening women's rights movement, The Happy Marriage explores not only the question of who's right and who's wrong, but also the very nature of modern matrimony. (Nick M.)

Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine by Diane Williams: Williams’s short stories operate according to the principles of Viktor Shklovsky’s ostranenie: making strange in order to reveal the ordinary anew. They are dense and dazzling oddities with an ear for patois and steeped deeply in the uncanny. Darkness and desire and despair and longing and schadenfreude and judgment roil just below the surface of seemingly pleasant exchanges, and, in their telling, subvert the reader’s expectations of just how a story unfolds. Williams’s previous collection Vicky Swanky Is a Beauty was a beauty. Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, Fine, her forthcoming, warns of linguistic breakdown, insistence, and restlessness. (Anne)

Mr. Splitfoot by Samantha Hunt: It’s been seven years since Samantha Hunt’s novel about Nicola Tesla, The Invention of Everything Else, was listed as an Orange Prize finalist. Now Hunt’s back with a modern gothic starring a scam-artist orphan who claims to talk to the dead; his sister who ages into a strange, silent woman; and, later, her pregnant niece, who follows her aunt on a trek across New York without exactly knowing why. Also featured: meteorites, a runaway nun, a noseless man, and a healthy dash of humor. Although it’s still too early to speculate on the prize-winning potential of Mr. Splitfoot, Hunt’s fantastical writing is already drawing favorable comparisons to Kelly Link and Aimee Bender, and her elegantly structured novel promises to be the year’s most unusual ghost story. (Kaulie)

The Kindness of Enemies by Leila Aboulela: Aboulela’s new novel transports readers to Scotland, the Caucasus, St. Petersburg, and Sudan. The protagonist is a Scottish-Sudanese lecturer researching "the lion of Dagestan,” a 19th-century leader who resisted Russian incursions, when she finds out that one of her students is his descendant. As they study up on the rebel leader, and the Georgian princess he captured as a bargaining chip, the two academics become embroiled in a cultural battle of their own. Aboulela’s fifth book sounds like a fascinating combination of Leo Tolstoy’s Hadji Murat and A.S. Byatt’s Possession. (Matt)

Girl Through Glass by Sari Wilson: With its intense competition and rivalries, the ballet world provides a novelist with plenty of dramatic material. Girl Through Glass alternates between late-1970s New York, where its heroine works her way into George Balanchine’s School of American Ballet, and the present day, where she is a dance professor having an affair with a student. Exploring the exquisite precision of dancing alongside the unruliness of passion, Wilson’s novel looks to be on point. (Matt)

Unspeakable Things by Kathleen Spivack: In her debut novel, Spivack, an accomplished poet, tells the story of a refugee family fleeing Europe during the final year of WWII. In New York City, where they’ve been laying low, we meet a cast of characters including a Hungarian countess, an Austrian civil servant, a German pediatrician, and an eight-year-old obsessed with her family's past -- especially some long-forgotten matters involving late night, secretive meetings with Grigori Rasputin. Described by turns as “wild, erotic” as well as "daring, haunting, dark, creepy, and surreal," Unspeakable Things certainly seems to live up to its title. (Nick M.)

What Belongs to You by Garth Greenwell: Greenwell’s debut novel expands his exquisitely written 2011 novella, Mitko. A meticulous stylist, Greenwell enlarges the story without losing its poetic tension. An American teacher of English in Bulgaria longs for Mitko, a hustler. Think the feel of James Salter’s A Sport and a Pastime. Greenwell’s lines tease and tear at the soul: “That my first encounter with Mitko B. ended in a betrayal, even a minor one, should have given me greater warning at the time, which should in turn have made my desire for him less, if not done away with it completely. But warning, in places like the bathrooms at the National Place of Culture, where we met, is like some element coterminous with the air, ubiquitous and inescapable, so that it becomes part of those who inhabit it, and thus part and parcel of the desire that draws us there.” (Nick R.)

On the Edge by Rafael Chirbes: This novel about the ills of Europe generally and Spain specifically appears in English mere months after the death of its author, one of Spain's premier novelists. Readers unmoved by, say, the sour hypotheticals of Michel Houellebecq will find a more nuanced, if no less depressing, portrait of economic decline and societal breakdown in On the Edge, the first of Chirbes's novels to be translated into English (by Margaret Jull Costa). (Lydia)

The Unfinished World by Amber Sparks: The second collection of short fiction by Sparks, The Unfinished World comprises 19 short (often very short) stories, surreal and fantastic numbers with titles like "The Lizzie Borden Jazz Babies" and "Janitor in Space." Sparks's first collection, May We Shed These Human Bodies, was The Atlantic Wire's small press debut of 2012. (Lydia)

And Again by Jessica Chiarella: This debut by current UC Riverside MFA student Chiarella is a speculative literary novel about four terminally ill patients who are given new, cloned bodies that are genetically perfect and unmarred by the environmental dangers of modern life. According to the jacket copy, these four people -- among them a congressman and a painter -- are "restored, and unmade, by this medical miracle." And Again is a January Indie Next Pick, and Laila Lalami calls it "a moving and beautifully crafted novel about the frailty of identity, the illusion of control, and the enduring power of love." (Edan)

February:

The High Mountains of Portugal by Yann Martel: The fourth novel by Martel is touted as an allegory that asks questions about loss, faith, suffering, and love. Sweeping from the 1600s to the present through three intersecting stories, this novel will no doubt be combed for comparison to his blockbuster -- nine million copies and still selling strong -- Life of Pi. And Martel will, no doubt, carry the comparisons well: “Once I’m in my little studio...there’s nothing here but my current novel,” he told The Globe and Mail. “I’m neither aware of the success of Life of Pi nor the sometimes very negative reviews Beatrice and Virgil got. That’s all on the outside.” (Claire)

The Queen of the Night by Alexander Chee: We’ve been awaiting Chee’s sophomore novel, and here it finally is! A sweeping historical story -- “a night at the opera you’ll wish never-ending,” says Helen Oyeyemi -- and the kind I personally love best, with a fictional protagonist moving among real historical figures. Lilliet Berne is a diva of 19th-century Paris opera on the cusp of world fame, but at what cost? Queen of the Night traffics in secrets, betrayal, intrigue, glitz, and grit. And if you can judge a book by its cover, this one’s a real killer. (Sonya)

The Lost Time Accidents by John Wray: Whiting Award-winner Wray’s fourth novel, The Lost Time Accidents, moves backwards and forwards in time, and across the Atlantic, while following the fates of two Austrian brothers. Their lives are immersed in the rich history of early-20th-century salon culture (intermingling with the likes of Gustav Klimt and Ludwig Wittgenstein), but then they diverge as one aids Adolf Hitler and the other moves to the West Village and becomes a sci-fi writer. When the former wakes one morning to discover that he has been exiled from time, he scrambles to find a way back in. This mash-up of sci-fi, time-travel, and family epic is both madcap and ambitious: “literature as high wire act without the net,” as put by Marlon James. (Anne)

A Doubter's Almanac by Ethan Canin: Canin is the New York Times bestselling author of The Palace Thief and America America and a faculty member at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Mathematical genius Milo Andret, subject of A Doubter’s Almanac, shares a home with Canin in northern Michigan. Milo travels to Berkeley, Princeton, Ohio, and back to the Midwest while studying and teaching mathematics. Later in the story, Hans, Milo’s son, reveals that he has been narrating his father’s mathematical triumphs and fall into addiction. Hans may be “scarred” by his father’s actions, but Canin finds a way to redeem him through love. (Cara)

Why We Came to the City by Kristopher Jansma: Kirkus described this book as an ode to friendship, but it could just as easily be described as a meditation on mortality. Jansma’s second novel -- his first was The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards, published in 2014 -- follows the intertwined lives and increasingly dark trajectories of a group of four young friends in New York City. (Emily)

Tender by Belinda McKeon: McKeon took her place among the prominent Irish novelists with her 2011 debut, Solace, which was voted Irish Book of the Year. Her second novel, Tender, follows the lifelong friendship of Catherine and James, who meet when they are both young in Dublin. At first she is a quiet college student and he the charismatic artist who brings her out of her shell, but McKeon follows their friendship through the years and their roles change, reverse, and become as complicated as they are dear. (Janet)

Wreck and Order by Hannah Tennant-Moore: Tennant-Moore’s debut novel, Wreck and Order, brings the audience into the life of Elsie, an intelligent young woman making self-destructive decisions. Economically privileged, she travels instead of attending college. Upon her return from Paris, she finds herself stuck in an abusive relationship and a job she hates -- so she leaves the U.S. again, this time for Sri Lanka. A starred review from Publishers Weekly says, “Tennant-Moore is far too sophisticated and nuanced a writer to allow Elsie to be miraculously healed by the mysterious East.” Tennant-Moore leaves the audience with questions about how to find oneself and one’s purpose. (Cara)

Dog Run Moon by Callan Wink: A few short years ago, Wink was a fly-fishing guide in Montana. Today, he has nearly bagged the limit of early literary successes, reeling in an NEA grant, a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford, and publications in The New Yorker, Granta, and the Best American Short Stories. “[T]hrough the transparency of his writing, at once delicate and brutally precise, the author gifts us with the wonderful feeling of knowing someone you’ve only met in a book,” Publishers Weekly says of Wink’s debut collection, which is mostly set in and around Yellowstone National Park. (Michael)

The Fugitives by Christopher Sorrentino: Ten years after Sorrentino’s much-lauded and National Book Award-nominated Trance, he returns with The Fugitives, called “something of a thriller, though more Richard Russo than Robert Ludlum,” by Kirkus. Within, struggling writer Sandy Mulligan leaves New York for a small, seemingly quiet Michigan town to escape scandal and finish his novel, and, well, does anything but. His name evokes Sorrentino’s father’s acclaimed novel Mulligan Stew, another tale of a struggling writer whose narrative falls apart. Mulligan’s novel suffers neglect as he befriends a swindler and becomes involved with an investigative reporter who's there to uncover the crime; Sorrentino’s plot, in contrast, is fine-tuned. (Anne)

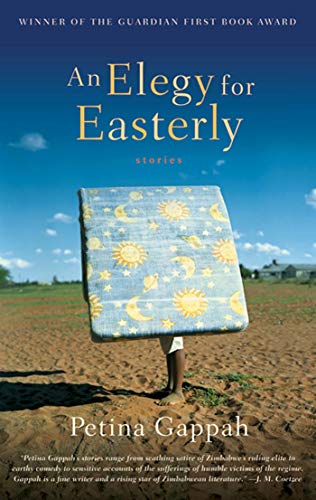

The Book of Memory by Petina Gappah: Gappah’s first book, a short story collection called An Elegy for Easterly, won the Guardian First Book Prize in 2009. The Book of Memory is her first novel, and if the first sentence of the description doesn’t hook you, I’m not sure what to tell you: “Memory is an albino woman languishing in Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison in Harare, Zimbabwe, where she has been convicted of murder.” The novel follows this “uniquely slippery narrator” as she pieces together her crime and the life that led her there. (Elizabeth)

Youngblood by Matthew Gallagher: In his debut work of fiction, Gallagher, a former U.S. Army captain, focuses his attentions on Jack Porter, a newly-minted lieutenant grappling with the drawdown of forces in Iraq. Struggling with the task of maintaining a delicate peace amongst warlords and militias, as well as the aggressive pressures being applied by a new commanding officer, Jack finds himself embroiled in a conflict between the nation he serves and the one he's supposedly been sent to help. Described as "truthful, urgent, grave and darkly funny" -- as well as "a slap in the face to a culture that's grown all too comfortable with the notion of endless war" -- this novel comes more than 12 years after George W. Bush declared, "Mission Accomplished," and nine months before we elect our next president. (Nick M.)

Black Deutschland by Darryl Pinckney: West Berlin in the years before the Wall came down -- “that petri dish of romantic radicalism” -- is the lush backdrop for Pinckney’s second novel, Black Deutschland. It’s the story of Jed Goodfinch, a young gay black man who flees his stifling hometown of Chicago for Berlin, hoping to recapture the magic decadence of W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood’s Weimar era and, in the process, remake and discover himself. In Berlin, Jed is free to become “that person I so admired, the black American expatriate.” Kirkus praises the novel for embodying the “inventive, idiosyncratic styles” now flourishing in African-American writing. (Bill)

Cities I've Never Lived In by Sara Majka: The linked stories in Majka’s debut collection beg the question how much of ourselves we leave behind with each departure we make, as we become “citizens of the places where we cannot stay.” Kelly Link offers high praise: “A collection that leaves you longing -- as one longs to return to much loved, much missed homes and communities and cities -- for places that you, the reader, have never been. Prodigal with insight into why and how people love and leave, and love again.” You can read excerpts at Catapult and Longreads. (Bruna)

The Heart by Maylis de Kerangal: De Kerangal, a short-lister for the Prix Goncourt, has not been widely translated in English, although this may change after this novel -- her first translation from an American publisher -- simultaneously ruins and elevates everyone's week/month/year. The Heart is a short and devastating account of a human heart (among other organs) as it makes its way from a dead person to a chronically ill person. It is part medical thriller, part reportage on the process of organ donation, part social study, part meditation on the unbearable pathos of life. (Lydia)

You Should Pity Us Instead by Amy Gustine: A debut collection of crisp short stories about people in various forms of extremis -- people with kidnapped sons, babies who won't stop crying, too many cats. The scenarios vary wildly in terms of their objective badness, but that's how life is, and the writer treats them all with gravity. (Lydia)

The Lives of Elves by Muriel Barbery: Following the hoopla around her surprise bestseller The Elegance of the Hedgehog, Barbery, trained as a philosopher, became anxious about expectations for the next book. She traveled, and went back to teaching philosophy. She told The Independent that for a time she had lost the desire to write. Eight years on, we have The Lives of Elves, the story of two 12-year-old girls in Italy and France who each discover the world of elves. Barbery says the book is neither a fairytale nor a parable, strictly speaking, but that she is interested in “enchantment” -- how the modern world is “cut off from” from its poetic illusions. (Sonya)

Square Wave by Mark de Silva: A dystopian debut set in America with a leitmotif of imperial power struggles in Sri Lanka in the 17th century. Part mystery, part sci-fi thriller, the novel reportedly deals with "the psychological effects of a militarized state upon its citizenry" -- highly topical for Americans today. Readers of The New York Times may recognize de Silva's name from the opinion section, where he was formerly a staffer. (Lydia)

The Arrangement by Ashley Warlick: Food writing fans may want to check out a novelization of the life of M.F.K. Fisher, focusing on, the title suggests, the more salacious personal details of the beloved food writer's life. (Lydia)

Sudden Death by Álvaro Enrigue: At once erudite and phantasmagoric, this novel begins with a 16th-century tennis match between the painter Caravaggio and the poet Francisco de Quevedo and swirls lysergically outward to take in the whole history of European conquest. It won awards in Spain and in Enrigue's native Mexico; now Natasha Wimmer gives us an English translation. (Garth)

The Daredevils by Gary Amdahl: Over the last decade, Amdahl has traced an eccentric orbit through the indie-press cosmos; his mixture of bleakness, comedy, and virtuosity recalls the Coen Brothers, or Stanley Elkin’s A Bad Man. The "Amdahl Library" project at Artistically Declined Press seems to be on hold for now, but perhaps this novel, about a young man riding the currents of radical politics and theater in the early-12th century, will bring him a wider audience. (Garth)

March:

What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours by Helen Oyeyemi: Oyeyemi wrote her first novel, The Icarus Girl, at 18 and was later included on Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists in 2013. Following her fifth release, the critically-praised novel Boy, Snow, Bird, in 2014, Oyeyemi is publishing her first collection of short stories. The stories draw on similar fairy tale themes as her past works. In What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours, Oyeyemi links her characters through literal and metaphorical keys -- to a house, a heart, a secret. If you can’t wait to get your hands on the collection, one of the stories, “‘Sorry’ Doesn’t Sweeten Her Tea,” was published in Ploughshares this summer. (Cara)

The Ancient Minstrel by Jim Harrison: With The Ancient Minstrel, our national treasure known as Jim Harrison returns to his greatest strength, the novella. Like Legends of the Fall, this new book is a trio of novellas that showcase Harrison’s seemingly limitless range. In the title piece, he has big fun at his own expense, spoofing an aging writer who wrestles with literary fame, his estranged wife, and an unplanned litter of piglets. In Eggs, a Montana woman attempting to have her first child reminisces about collecting eggs at her grandparents’ country home in England. And in The Case of the Howling Buddhas, retired detective Sunderson returns from earlier novels to investigate a bizarre cult. The book abounds with Harrison’s twin trademarks: wisdom and humor. (Bill)

The Throwback Special by Chris Bachelder: As a fan of sports talk radio and its obsessive analysis, I’m looking forward to Bachelder’s novel, which endlessly dissects the brutal 1985 play where Lawrence Taylor sacked Washington’s quarterback Joe Theismann, breaking his leg. In the novel, 22 friends meet to reenact the play, an occasion that allows Bacheler to philosophize about memory and the inherent chaos of sports. As he put it in a New York Times essay: “I’m moved...by the chasm...between heady design and disappointing outcome, between idealistic grandeur and violent calamity.” (Matt)

The Year of the Runaways by Sunjeev Sahota: Sahota’s second novel is the only title on the 2015 Man Booker Prize shortlist that has yet to be published in the United States. It tells the story of four Indians who emigrate to the north of England and find their lives twisted together in the process. Many critics cited its power as a political novel, particularly in a year when migration has dominated news cycles. But it works on multiple levels: The Guardian’s reviewer wrote, “This is a novel that takes on the largest questions and still shines in its smallest details.” (Elizabeth)

Burning Down the House by Jane Mendelsohn: The author of the 1990s bestseller I Was Amelia Earhart here focuses on a wealthy New York family beset by internal rivalries and an involvement, perhaps unwitting, in a dark underworld of international crime. Mendelsohn’s novel hopscotches the globe from Manhattan to London, Rome, Laos, and Turkey, trailing intrigue and ill-spent fortunes. (Michael)

Stork Mountain by Miroslav Penkov: In this first novel from Penkov (author of the story collection East of the West), a young Bulgarian immigrant returns to the borderlands of his home country in search of his grandfather. Molly Antopol calls it “a gorgeous and big-hearted novel that manages to be both a page-turning adventure story and a nuanced meditation on the meaning of home.” (Bruna)

Gone with the Mind by Mark Leyner: With novels like Et Tu, Babe and The Sugar Frosted Nutsack, Leyner was one of the postmodern darlings of the 1990s (or you may remember him sitting around the table with Jonathan Franzen and David Foster Wallace for the legendary Charlie Rose segment). After spending almost the last decade on non-fiction and movie projects, he’s back with a new novel in which the fictional Mark Leyner reads from his autobiography at a reading set up by his mother at a New Jersey mall’s food court. Mark, his mother, and a few Panda Express employees share an evening that is absurd and profound -- basically Leyneresque. (Janet)

Innocents and Others by Dana Spiotta: “Maybe I’m a writer so I have an excuse to do research,” Spiotta said of what she enjoys about the writing process. And yet, for all of her research, she avoids the pitfalls of imagination harnessed by fact. In fact, Spiotta’s fourth and latest novel, Innocents and Others, is nearly filmic, channeling Jean-Luc Godard, according to Rachel Kushner, and “like classic JLG is brilliant, and erotic, and pop.” Turn to The New Yorker excerpt to see for yourself: witness Jelly, a loner who uses the phone as a tool for calculated seduction, and in doing so seduces the reader, too. (Anne)

Prodigals by Greg Jackson: Jackson’s collection opens with a story originally published in The New Yorker, ”Wagner in the Desert,” a crackling tale of debauchery set in Palm Springs. In it, a group of highly-educated, creative, and successful friends seek to “baptize [their] minds in an enforced nullity.” They also repeatedly attempt to go on a hike. The wonderfully titled “Serve-and-Volley, Near Vichy,” in which a former tennis star enlists his houseguest in a bizarre project, and the eerily beautiful “Tanner’s Sisters” are two particularly memorable stories in this sharp and often haunting debut. (Matt)

Shelter by Jung Yun: Yun’s debut novel concerns Kyung Cho: a husband, father, and college professor in financial trouble who can no longer afford his home. When his own parents -- whom he barely tolerates because they’ve never shown him warmth and affection -- are faced with violence and must move in with him, Cho can no longer hide his anger and resentment toward them. The jacket copy compares the book to Affliction and House of Sand and Fog, and James Scott, author of The Kept, calls it “an urgent novel.” Yun’s work has previously been published in Tin House. (Edan)

99 Poems: New and Selected by Dana Gioia: A gifted poet of rhythm and reason, Gioia’s civic and critical pedigree is impressive. A previous chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, Gioia was recently named California’s Poet Laureate. In recent years Gioia’s critical writing has taken precedence -- his 2013 essay “The Catholic Writer Today” is already a classic in its genre - but this new and selected collection marks his return to verse. Graywolf is Gioia’s longtime publisher, so look for emblematic works like “Becoming a Redwood” next to new poems like “Hot Summer Night:” “Let’s live in the flesh and not on a screen. / Let’s dress like people who want to be seen.” (Nick R.)

Margaret the First by Danielle Dutton: “I had rather be a meteor, singly, alone,” writes Margaret Cavendish, the titular character in Dutton’s novel Margaret the First. Cavendish is “a shy but audacious” woman of letters, whose writing and ambitions were ahead of her time. The taut prose and supple backdrop of courtly life are irresistible. (Witness: quail in broth and oysters; bowls stuffed with winter roses, petals tissue-thin; strange instruments set beside snuffboxes.) Dutton is something of a meteor herself, as founder of the Dorothy Project and with two wondrous books already under her belt, including the Believer Book Award-nominated novel Sprawl. (Anne)

The North Water by Ian McGuire: A raw and compulsively readable swashbuckler about the whaling business, with violence and intrigue in dirty port towns and on the high seas. There are many disturbing interactions between people and people, and people and animals -- think The Revenant for the Arctic Circle. This is McGuire's second novel; he is also the author of the "refreshingly low-minded campus novel" Incredible Bodies. (Lydia)

Blackass by A. Igoni Barrett: A young middle-class Nigerian man wakes up in his bed one morning to find that he has become white in the night. As a consequence, he loses his family but gains all manner of undeserved and unsolicited privileges, from management positions at various enterprises to the favors of beautiful women from the upper crust of Lagos society. His dizzying tragicomic odyssey paints a vivid portrait of the social and economic complexities of a modern megacity. (Lydia)

The Nest by Cynthia D'Aprix Sweeney: D’Aprix Sweeney’s debut novel The Nest will hit shelves in March trailing seductive pre-hype: we learned last December that the book was sold to Ecco for seven figures, and that it’s the story of a wealthy, “spectacularly dysfunctional” family -- which for me brings to mind John Cheever, or maybe even the TV series Bloodlines, in which one of the siblings is a particular mess and the others have to deal with him. But The Nest has been described as “warm,” “funny,” and “tender,” so perhaps the novel is more an antidote to the darkness in family dysfunction we’ve known and loved -- fucked-up families with hearts of gold? (Sonya)

What Lies Between Us by Nayomi Munaweera: A novel about a mother and daughter who leave Sri Lanka after a domestic disturbance and struggle to find happiness in the United States. Munaweera won the Regional Commonwealth Book Prize for Asia for her first novel, Island of a Thousand Mirrors. (Lydia)

The Association of Small Bombs by Karan Mahajan: A novelist examines the enduring fallout of a "small" terrorist attack in a Delhi marketplace, and the way that families, politics, and pain weave together. Mahajan's first novel, Family Planning, was a finalist for the Dylan Thomas prize. (Lydia)

Hold Still by Lynn Steger Strong: An emotionally suspenseful debut about the relationship between a mother and her troubled young daughter, who commits an unfixable indiscretion that implicates them both. (Lydia)

Dodge Rose by Jack Cox: This young Australian has evidently made a close study of James Joyce and Samuel Beckett (and maybe of Henry Green) -- and sets out in his first novel to recover and extend their enchantments. A small plot of plot -- two cousins, newly introduced, attempt to settle the estate of an aunt -- becomes the launch pad for all manner of prose pyrotechnics. (Garth)

High Dive by Jonathan Lee: The Assassination of Margaret Thatcher could have been the title of Lee's first novel, had Hilary Mantel not taken it for her 2014 short story collection. The similarities end with the subject matter, though. Where Mantel opted for a tight focus, Lee's novel uses a real-life attempt to blow up Mrs. Thatcher as an opportunity to examine other, less public lives. (Garth)

April:

My Struggle: Book Five by Karl Ove Knausgaard: Translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett, the fifth installment of this six-volume autobiographical novel covers Knausgaard’s early adulthood. The book is about a love affair, alcoholism, death, and the author’s struggle to write. James Wood describes Knausgaard’s prose as “intense and vital […] Knausgaard is utterly honest, unafraid to voice universal anxieties.” (Bruna)

Eligible by Curtis Sittenfeld: In Sittenfeld's modern retelling of Pride and Prejudice, Liz is a New York City magazine writer and Darcy is a Cincinnati neurosurgeon. Although the update is certainly on trend with themes of CrossFit and reality TV, Sittenfeld is an obvious choice to recreate Jane Austen's comedy of manners. From her boarding school debut, Prep, to the much-lauded American Wife, a thinly veiled imagination of Laura Bush, Sittenfeld is a master at dissecting social norms to reveal the truths of human nature underneath. (Tess)

Alice & Oliver by Charles Bock: The author’s wife, Diana Colbert, died of leukemia in 2011 when their daughter was only three years old. Inspired in part by this personal tragedy, this second novel by the author of 2008’s Beautiful Children traces a day in the life of a young New York couple with a new baby after the wife is diagnosed with cancer. “I can’t remember the last time I stayed up all night to finish a book,” enthuses novelist Ayelet Waldman. “This novel laid me waste.” (Michael)

Our Young Man by Edmund White: White’s 13th novel sees a young Frenchman, Guy, leave home for New York City, where he begins a modeling career that catapults him to the heights of the fashion world. His looks, which lend him enduring popularity amongst his gay cohort on Fire Island, stay youthful for decades, allowing him to keep modeling until he’s 35. As the novel takes place in the '70s and '80s, it touches on the cataclysm of the AIDS crisis. (Thom)

Now and Again by Charlotte Rogan: After harboring a secret writing habit for years, Rogan burst onto the bestseller list with her debut novel, The Lifeboat, which was praised for its portrayal of a complex heroine who, according to The New York Times, is “astute, conniving, comic and affecting.” Rogan’s second novel, Now and Again, stars an equally intricate secretary who finds proof of a high-level cover-up at the munitions plant where she works. It is both a topical look at whistleblowers and a critique of the Iraq War military-industrial complex. Teddy Wayne calls it “the novel we deserve for the war we didn't.” (Claire)

Hystopia by David Means: After four published books, a rap sheet of prizes, and six short stories in The New Yorker, Means is coming out with his debut novel this spring. Hystopia is both the name of the book and a book-within-the-book, and it revolves around Eugene Allen, a Vietnam vet who comes up with an alternate history. In Allen’s bizarre, heady what-if, John F. Kennedy survives the '60s, at the end of which he creates an agency called the Psych Corps that uses drugs to wipe traumas from people’s brains. (Thom)