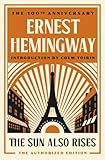

In June 1925, Ernest Hemingway turned to a blank page in his notebook and scrawled these five hopeful words:

Along With Youth

A Novel

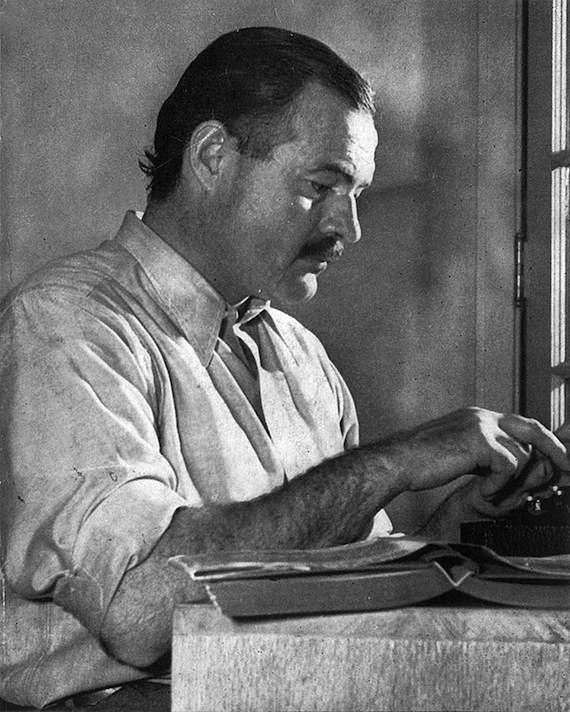

Hemingway was 25 years old, living in a cramped Paris apartment with his wife Hadley and their two-year-old son, Jack. He had published two chapbooks with tiny presses in Paris, and sold a collection of stories, In Our Time, to a New York publisher. In Our Time is now a classic, its stories taught in high school and college classrooms around the world, but his advance was just $200 and Hemingway understood that if he didn’t follow the collection up with a novel, it would probably sell a few hundred copies and disappear.

Along With Youth was a sea story, apparently, set on a troop ship in 1918 and featuring Nick Adams, the Hemingway stand-in who stars in many of the stories in In Our Time. In the opening scene, Nick Adams talks with some Polish officers on the deck of the ship while someone strums a mandolin in the background. The book continued in this vein for 27 largely plotless pages until Hemingway gave up and packed his bags for his annual summer pilgrimage to the bullfights in Pamplona, Spain. Just two months later, in September 1925, he had finished a draft of The Sun Also Rises, the novel that would launch his career.

Along With Youth was a sea story, apparently, set on a troop ship in 1918 and featuring Nick Adams, the Hemingway stand-in who stars in many of the stories in In Our Time. In the opening scene, Nick Adams talks with some Polish officers on the deck of the ship while someone strums a mandolin in the background. The book continued in this vein for 27 largely plotless pages until Hemingway gave up and packed his bags for his annual summer pilgrimage to the bullfights in Pamplona, Spain. Just two months later, in September 1925, he had finished a draft of The Sun Also Rises, the novel that would launch his career.

Hemingway’s epic week of partying at Pamplona’s fiesta de San Fermín in July 1925 is the centerpiece of Lesley M. M. Blume’s new book Everybody Behaves Badly, which traces Hemingway’s rise from a promising young proto-hipster sweating out sentences in a Paris garret to one of the 20th century’s most influential prose stylists.

Ninety years on, it can be hard for readers to comprehend the revelatory shock The Sun Also Rises delivered to its original audience. Yes, the sexuality and decadence of Hemingway’s characters raised eyebrows in a country where Prohibition was still in effect and adultery was against the law in most states. But it went deeper than that. The First World War upended a dynastic landed gentry that had patronized the arts for centuries, and new technologies, most notably movies and mass-circulation magazines, were bringing art and literature to a far wider audience than ever before.

Paris was Ground Zero for the artistic response to these social and technological revolutions, and Hemingway’s innovation was to make the formal experiments of the Parisian avant garde accessible to middlebrow readers. “My book will be praised by highbrows and can be read by lowbrows,” he wrote to Horace Liveright, publisher of In Our Time. “There is no writing in it that anybody with a high-school education cannot read.”

Hemingway was ideally suited to this role of middlebrow revolutionary. He was not only an American, but a Midwesterner, raised in the Chicago suburbs far removed from the urban cultural elite. Also, unlike many of his fellow Modernists, who attended the best universities in Europe and the U.S., Hemingway never went to college and served his apprenticeship not at Harvard or University College Dublin, but in the newsrooms of provincial newspapers and in the cafés and salons of Paris.

This, the story of how Hemingway became Hemingway, is the subject of Everybody Behaves Badly. It’s a tale that has been told many times, but it bears repeating, in part because the version that most people know, the one told by Hemingway in his posthumous memoir A Moveable Feast, is so deeply disingenuous, and in part because it demystifies the legend and makes Hemingway’s achievement comprehensible in human terms.

This, the story of how Hemingway became Hemingway, is the subject of Everybody Behaves Badly. It’s a tale that has been told many times, but it bears repeating, in part because the version that most people know, the one told by Hemingway in his posthumous memoir A Moveable Feast, is so deeply disingenuous, and in part because it demystifies the legend and makes Hemingway’s achievement comprehensible in human terms.

The Hemingway of Blume’s book is not especially likeable. In A Moveable Feast, he paints his Paris years as a time of almost sacred poverty (“Hunger is good discipline and you learn from it,” etc., etc.), neatly eliding the fact that for much of his Paris period, he lived off his wife’s trust fund. Like many men who pride themselves on their toughness and self-reliance, Hemingway was almost comically insecure and prone to betray anyone who had the effrontery to do him a favor. In a typically gratuitous move, he repaid Sherwood Anderson, who had given Hemingway crucial letters of introduction to Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound, by writing The Torrents of Spring, a poisonous and unfunny satire of Anderson’s novel Dark Laughter.

But if the young Hemingway was an asshole, and he was, he was a preternaturally talented and savvy one. In Everybody Behaves Badly, he seeks out the high priests of the Parisian avant garde one by one, soaking up what each has to teach him before abruptly casting them aside. Their influence permeates his work, from the stream-of-consciousness riffs in his stories to the famous epigraph to The Sun Also Rises — “You are all a lost generation” — supplied by Stein.

But nothing exerted a more profound influence on Hemingway’s fiction than his work as a reporter. Hemingway wrote for newspapers, principally the Toronto Star, off and on for about four years, filing from war zones and writing travel and feature pieces about expat life in Europe. He never loved the work, and after a disastrous stint at the home office of the Star in Toronto he quit altogether to live off Hadley’s trust fund, but news writing not only gave his prose its signature economy of expression and coolly objective tone, it taught him to see the news value in a story. It’s not for nothing that Hemingway knocked out a draft of The Sun Also Rises in a matter of weeks. He saw in his 1925 trip to Pamplona a perfect vehicle for telling the hot story of the dissipated post-war generation in Europe, and he wanted to get it into print before it went stale.

The first draft of The Sun Also Rises was so close to reportage that Hemingway didn’t even change the characters’ names. The most famous of these are Lady Duff Twysden and Harold Loeb, whom Hemingway immortalized in the published version as Lady Brett Ashley and her moony former lover Robert Cohn. Along for the ride in Pamplona was Twysden’s fiancé, Pat Guthrie, who like his fictional alter ego Mike Campbell was an alcoholic bankrupt who put up with Twysden’s compulsive promiscuity. In life as in fiction, shortly before the Pamplona trip, Twysden had run off with Loeb for a sex-soaked weekend at a seaside resort — and in life as in fiction, the affair was just as much over for Twysden as it was alive for poor, lovestruck Loeb.

Then there’s Hemingway himself, the model for the novel’s narrator, Jake Barnes. Blume says it’s unclear whether Hemingway had an affair with Twysden, but he was clearly fascinated by her and deeply envious of Loeb, whose first novel, Doodab, was set for publication in New York later that year. Then, too, in the summer of 1925, Hemingway was trapped between his unraveling marriage to Hadley and a nascent affair with his soon-to-be second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer.

In The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway airbrushes Hadley out of the tale and gives his alter ego, Jake Barnes, a war wound that renders him impotent while still allowing him the full range of romantic and sexual desire. As literary strategies go, this is a stroke of genius, transforming his autobiographical narrator from a husband with a wandering eye to poignant, wounded hero. But it’s more than that, too. In the architecture of the novel, Jake’s war injury turns him into that rarest of beasts: a knowing innocent, a man of appetites who is incapable of sin.

This works so well because, like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, published just the year before, The Sun Also Rises is a novel about the tyranny of unbounded appetite. Hemingway’s characters spend the book consuming things: drink, food, bloody spectacle, each other. “It kept up day and night for seven days,” he writes of the fiesta. “The dancing kept up, the drinking kept up, the noise went on. The things that happened could only have happened during a fiesta. Everything became quite unreal finally and it seemed as though nothing could have any consequence. It seemed out of place to think of consequences during the fiesta.”

This works so well because, like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, published just the year before, The Sun Also Rises is a novel about the tyranny of unbounded appetite. Hemingway’s characters spend the book consuming things: drink, food, bloody spectacle, each other. “It kept up day and night for seven days,” he writes of the fiesta. “The dancing kept up, the drinking kept up, the noise went on. The things that happened could only have happened during a fiesta. Everything became quite unreal finally and it seemed as though nothing could have any consequence. It seemed out of place to think of consequences during the fiesta.”

What is true in Pamplona is true in more subtle ways elsewhere in the novel. None of the characters are tied down by marriage or have children to care for. Except for Jake, they have no visible employment, and thus no jobs to lose. They either have enough money not have to worry about it, or are so perpetually broke that it has ceased to worry them. This, more than the war, which has little practical effect on anyone but Jake, is what makes them “lost.” They lead lives in which their actions have ceased to have meaningful consequences. This is why Robert Cohn is so furious at Lady Brett: He wants their affair to have meant something, if not to her, then at least to the other men who are in love with her, Jake and Mike Campbell.

In a traditional novel, the kind that the Parisian avant garde sought to outmode, this heedlessness would spell the characters’ doom. The temptress Lady Brett would have to be destroyed so bourgeois society could carry on, in the way Jay Gatsby must be destroyed at the end of The Great Gatsby. But nothing like that happens in The Sun Also Rises. In Pamplona, Brett seduces a 19-year-old bullfighter, Pedro Romero, the walking epitome of the Hemingway hero: handsome, self-assured, brave without artifice. “Romero’s bull-fighting gave real emotion,” Hemingway writes, “because he kept the absolute purity of line in his movements and always quietly and calmly let the horns pass him each time.”

Here at last, after hundreds of pages of drinking and eating and fucking, is the act that tears at the social fabric of the novel. Lady Brett seduces the pure young bullfighter, with Jake himself providing the introductions, yet no one in the novel suffers real consequence. After his first night with Brett, Romero performs so well in the ring that he is allowed to cut off a bull’s ear as a trophy, and after their affair has run its course, Brett sends him on his way, and slithers back to her long-suffering fiancé.

This, finally, is the true modernity of Hemingway’s novel. In the fictive world of F. Scott Fitzgerald, a brilliant 20th-century stylist with a 19th-century sensibility, Gatsby must die for the sin of daring to rise above his station and love whomever he wants. In the fictive world of The Sun Also Rises, Lady Brett Ashley, the witty, decadent castoff of Britain’s dying aristocracy, can live however the hell she pleases without it costing her a thing.

Except that it does cost her one thing: Jake Barnes. A central conceit of the novel is that Jake would marry Brett but doesn’t because he can’t physically consummate the relationship, but after her affair with Romero, Jake finally tires of his high-maintenance girlfriend. When Brett tells him, “You know it makes one feel rather good deciding not to be a bitch…It’s sort of what we have instead of God,” Jake replies wryly: “Some people have God.” And a little later when Brett tries to weasel back into his affections, saying, “Oh Jake, we could have had such a damned good time together,” he responds with perhaps the most famous last line in American literature: “Yes. Isn’t it pretty to think so?”

And there it is, the revolution of the middlebrow. With an act of literary sleight of hand only a master could pull off, Hemingway manages to have it both ways: Lady Brett and her ilk live in a modern amoral world without consequences, and yet we his readers, through the eyes of Jake Barnes, the hard-boiled innocent, have judged her and found her wanting.

Image Credit: Wikipedia.