I have an almost full collection of Hanuman Books, the thumb-size editions handmade by the press founded in 1986 by Raymond Foye and Francesco Clemente. They are kept in a glass box and were a gift to my husband. He hasn’t looked at one yet. I can’t stop thinking about them. It was the acid covers with gold leaf titles that initially attracted me to the set; they looked so charming piled together. I am neither art critic nor expert, but I am curious and was drawn to further inquiry. I guess saying they were a present was the best cover for smuggling them into my house. I fell in love with the tightly edited cast of avant-garde works and hard-to-find translations. Here were Henri Michaux and Dodie Bellamy and Bob Flanagan and Eileen Myles and other writers and artists that created works that can be difficult to categorize by genre or media. Foye and Clemente had successfully created objects that were cult and cool and brave and lasting.

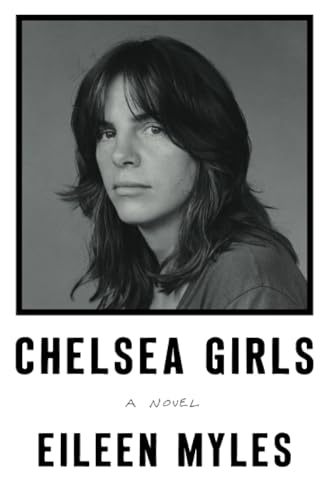

I wasn’t completely surprised to hear that this September, HarperCollins will be publishing Myles’s Chelsea Girls. It was Myles, herself, who told me that Chelsea Girls was, at first, “something stapled” and published by John Martin’s Black Sparrow Press, perhaps best known for introducing Charles Bukowski. I love the romance of this, and of an East Village poet and writer whom people say is about to have a moment; an overnight success after 40 years.

Chelsea Girls is an example of a hybrid work that’s taken on cult status. It’s considered an autobiographical novel, straddling the space between nonfiction and fiction. One of the times I meet up with Myles, she is just back from a panel at AWP, the big writers’ conference, with Maggie Nelson, Eula Bliss, and Leslie Jamison, among others, at which she turned to them and said, “Isn’t it a fugitive form you guys are creating?” Well said.

Myles notes that, like her, many of these writers of fugitive form are also poets. And it is social media that, unsurprisingly, has helped to push this once avant-garde approach into the mainstream. She talks about the fluidity of Twitter and Instagram (she’s active on both), the flow of images and captions, and what’s real and what’s not — considering our intention to portray something altogether different than one’s reality, only the best parts.

“Can we acknowledge part of it (hybrid works) is happening because of social media and engagement with the photograph and film?” Myles sees prose writing in these forms as a natural response to the inundation of images and accompanying words on social media. “The word ‘literary’ is out the window because of all these new forms; the original of the book is no longer the book! It’s not a collective intelligence, it’s a collecting intelligence!” She cites Bellamy, Kathy Acker, Chris Kraus and even Violette le Duc as examples of writers who have long trafficked in this fluid space. From here, there’s the aforementioned panelists, and others like Sheila Heti and Miranda July. Maybe fugitive form is the new intermedia?

In a 1965 essay, “Synthesthesia and Intersense: Intermedia,” early Fluxus artist and publisher Dick Higgins offers the term “intermedia” taken from the writings of Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1812. He writes, “We are approaching the dawn of a classless society, to which separation into rigid categories is absolutely irrelevant.” He mentions Marcel Duchamp as an early adopter of this play with his readymades, and further examples range from John Cage’s “music and philosophy” to Robert Rauschenberg’s “combines” or Allan Kaprow and Al Hansen’s “Happenings.”

In 1981, Higgins wrote a follow-up essay explaining that his intention was “to offer a means of ingress into works,” to abate fear of new forms, to not be “dismissed as avant-garde: for specialists only.” He was worried that he may have overvalued the term, in his efforts to “popularize” avant-garde intermedia. It is a thoughtful meditation that is as important today as then, but for different reasons. Higgins established Something Else Press in 1964 (-1974) and it was in his first newsletter that he would publish “Synthesthesia and Intersense,” arguing: “It seemed foolish simply to publish my little essay in some existing magazine, where it could be shelved or forgotten.” Today it could have appeared and lived on a website like this one.

Something Else Press intrigues me, much in the same way as Hanuman Books. It sought to create objects with an emphasis on decimating the avant-garde in a pre-Internet world. I reached out to Higgins’s daughter with fellow Fluxus artist Alison Knowles. Hannah Higgins is a professor of art history at the University of Illinois Chicago.

She told me an interesting anecdote about her father attending boarding school in Vermont and becoming friends with Andre Breton’s daughter Aube, who had been sent there when her parents left France. “I think that’s fundamentally when Dick became Dick,” Hannah says of imagining him “being entertained with stories of the French avant-garde.”

When Dick went to Alison and told her he was starting a press, he said he was going to give it a Marxist-friendly title, Shirtsleeves, as in rolling up your sleeves. Call it “something else,” she said. And it was decided.

Dick would go on to publish A Primer of Happenings & Time/Space Art, Al Hansen’s book about performance art, and to publish the likes of Emmet Williams’s “machine driven schema” computer poetry and the last work ever published by Duchamp. It was Knowles who was very close to Duchamp. (“John Cage introduced me to Marcel so we could do the print Coeur Volants together. Which we did,” she writes me.) It is noteworthy that Dick was in Cage’s composition class at the New School for Social Research, as was Hansen.

I corresponded with Bibbe Hansen, Al’s daughter, Andy Warhol-intimate, and, interestingly, the musician Beck’s mother. Of Something Else Press, which, of course, published her father, Hansen says, “The work was so little regarded or championed in its time, I think Something Else Press perhaps helped to archive these works until history and culture were able to catch up,” she says. “These valiant Davids played a vital and important role in a world of publishing Goliaths disinterested in anything untried or new.”

And here’s where I start to worry. I am worried that it’s not the innovators or early adopters that are getting play in publications where one needs to be vetted by a select few before being promoted by them. This leads me to consider the concessions and compromises being made even by these publications in an effort to garner “hits” and gain “followers.” Characters that were once forbidden now appear on covers. And we are turned upside down, because it’s suddenly not the hard work that’s being promoted, but something else altogether. We allow certain names to guest edit publications in an effort to get readers; we are taken with the commodity of youth culture. And all for good reason. I don’t condemn any of this, rather ask for a kind of awareness through the perspective of the ’60s era avant-garde, small presses, friendships, and networks. And I agree with Myles that there has to be a kind of authenticity to the collective intelligence, simply because it is so.

I ask Bibbe Hansen how she imagines social media would play out were it around while she was growing up: “Well, Andy would have LOVED it! HE would have been KING of Tweets!” She’s one of the few people with the credibility to say this.

“The avant-garde was always a game of friends,” Hannah says. “If you actually look at what’s driving those texts it’s intimate, small meetings, people, and one-to-one encounters. You hear from artists all the time that they can’t be friends with someone whose work they really hate, so you’ll tend to get social networks that are affinity networks, as well. It wasn’t just that Dick was publishing his friend and lovers, but that he could love them deeply if he really respected and admired their work.”

Hannah says,“But if the work is even to become truly important to large numbers of people, it will be because the new medium allows for greater significance, not simply because it’s formal nature assures it of relevance.” She explains Dick’s emphasis — that it wasn’t about social or geographic “climbing” to the latest, greatest big name, rather creating a “place” where people, friend, children, other artists, are affected by the work.

When I first met Myles and we talked about her experience with Hanuman Books, she also told me that these publications were driven by “intimate encounters,” meaning networks and relationships among artists. “These small presses have been the microphone for groundbreaking work.”

Myles believes that friendship and love have to be the reason you publish books. She prescribes publishers to “learn to represent, and not gamble,” which seems to me just right.

But then, how to push aside worrying about the other, louder, bigger voices. Myles tells me her take on a “celebrity” with over 20 million followers: “The essential fact that there’s something wrong, but something right. Think about it,” she says. “I love that it’s messy.”

So, what’s one to do?

“Find a messy team and write for them.”

Play the game, but do the work.

And now, Myles is about to have a “moment.” Only, she’s been living this moment her whole adult life, and as Chelsea Girls tells it, even before.