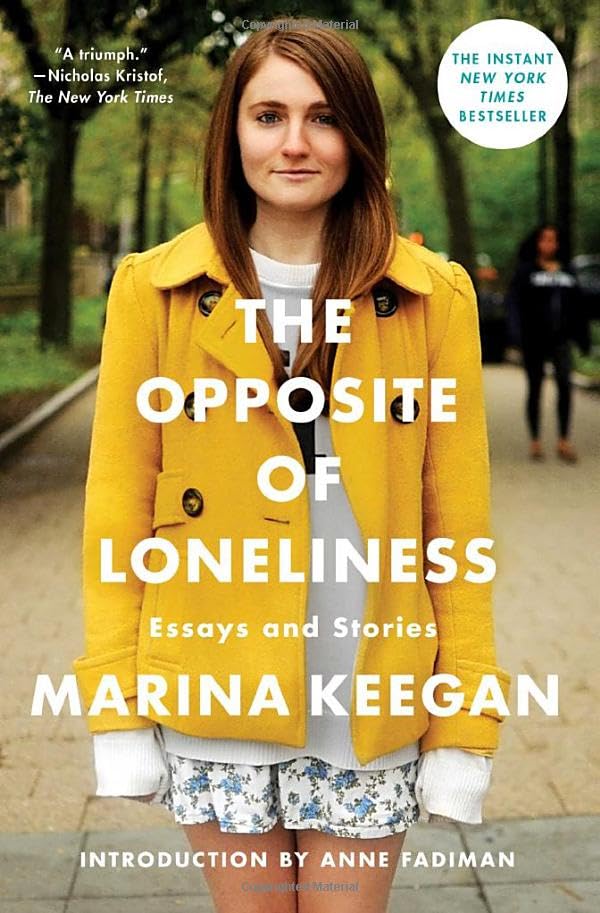

If demographic information matters, allow me to share mine. I am 22. I am a recent college graduate, and I have a degree in English literature. I am what the internet, sociologists, and The New York Times call a “Millennial.” I am occasionally tempted to believe that this is all unique, that I am truly individual. But the truth is that all this identifying information applies equally well to thousands and thousands of other 22-year-old girls who want to be writers and editors, and it was equally true of Marina Keegan, the Yale student who died in a car accident five days after her graduation in 2012 and whose last essay went viral in the following months. She was 22. She studied literature and creative writing. She wanted to be a writer. She didn’t seem to like the term “Millennial” very much. We were and are very similar. Except that, of course, we aren’t. Not really.

It’s maybe too easy to boil down Keegan’s posthumous collection of essays and stories, The Opposite of Loneliness, to these kinds of biographical snapshots and broad generalizations. Many reviews of the book place an incredible emphasis on the youth of the writing, the way Keegan’s voice sounds 22 (which it is), and the way that her stories and essays capture the anxieties and ambiguities and joys of being young and alive and in college (which she was). Her characters text, they email, they go through each others’ Facebook albums. “This,” the critics seem to be saying, “is the future of literature. When the Millennials come of age, this is what they will all be writing.”

But the other focus, and the one that’s harder to shake, is on Keegan herself, on her promise and her tragedy. How terrible, the book seems to be saying, that such a girl should die so young. The blurbs on the back cover of the book are all elegies. “I will never stop mourning,” begins the first, from Harold Bloom. Another refers to the collection as “the writing Marina Keegan left behind.” The last begins “In her brief life…” and ends with “Though every sentence throbs with what might have been, this remarkable collection is ultimately joyful and inspiring, because it represents the wonder that she was.” All of which seem to undermine and contradict Anne Fadiman’s warning in her (elegiac, mournful) foreword: “Marina wouldn’t want to be remembered because she’s dead. She would want to be remembered because she’s good.”

And she is. She’s very good. The collection, though uneven, is strong and varied. For the most part it isn’t student writing, and the first story is enough to disprove any concerns that Keegan is only being remembered for her death. In “Cold Pastoral” the young, female narrator’s boyfriend suddenly dies, and she is thrown together with both the ex he was still in love with and the full story of their long romance in the form of the dead boyfriend’s diary. The characters are complicated and believable, and it is here that all the strongest elements of Keegan’s writing are present. The students go to a house party; they talk about hooking up. They are young and in college and uncertain about how to process grief, the disappearance of one of their own, and also about how to define their relationships, how to structure and understand their own lives. The end is both surprising and satisfying. Every character acts both naturally and originally; I wouldn’t have made the same choices, were I in their places (largely due to my deep reverence for diaries), but I can see why they make the choices they do. The story was easily my favorite of the collection, and I thought about it long after I finished the book.

This particular story also exemplifies a somewhat eerie trend in Keegan’s writing – a lot of characters die, and many of the nonfiction pieces examine death and dying while making reference to Keegan’s own fears and losses. These are both thoughtful and extremely difficult to read. It’s as if Keegan herself won’t let you forget that she’s gone, that she’ll never get to eat the cheese pizza she requested for her death bed, that all her worries about premature cancer were for naught, that she won’t get to keep driving her grandmother’s 1990 Camry. The essays in the collection are, as a whole, not as strong as the fiction – they are shorter, slighter, and move almost too quickly from point to point, giving them a kind of frantic energy – but they are personal, and in this context that seems to count more than anything. Though rough, the nonfiction’s unpolished forms introduce the reader to Keegan more directly. We learn about her experience watching beached whales unhinge their jaws and breathe dying breaths; we have to admire her youthful honesty and bravado when she wishes she had thought to rewrite Mrs. Dalloway before Michael Cunningham. In “Putting the ‘Fun’ Back in Eschatology” Keegan worries about the death of the sun and the end of human culture. She doesn’t “want to let the universe down,” and though this is a melodramatic sentiment, it’s nevertheless charming in its sincerity. These writings are raw, and they make the reader ache as they get to know Keegan in greater and greater detail, as more and more of her personality is revealed and we realize how much has been lost.

This particular story also exemplifies a somewhat eerie trend in Keegan’s writing – a lot of characters die, and many of the nonfiction pieces examine death and dying while making reference to Keegan’s own fears and losses. These are both thoughtful and extremely difficult to read. It’s as if Keegan herself won’t let you forget that she’s gone, that she’ll never get to eat the cheese pizza she requested for her death bed, that all her worries about premature cancer were for naught, that she won’t get to keep driving her grandmother’s 1990 Camry. The essays in the collection are, as a whole, not as strong as the fiction – they are shorter, slighter, and move almost too quickly from point to point, giving them a kind of frantic energy – but they are personal, and in this context that seems to count more than anything. Though rough, the nonfiction’s unpolished forms introduce the reader to Keegan more directly. We learn about her experience watching beached whales unhinge their jaws and breathe dying breaths; we have to admire her youthful honesty and bravado when she wishes she had thought to rewrite Mrs. Dalloway before Michael Cunningham. In “Putting the ‘Fun’ Back in Eschatology” Keegan worries about the death of the sun and the end of human culture. She doesn’t “want to let the universe down,” and though this is a melodramatic sentiment, it’s nevertheless charming in its sincerity. These writings are raw, and they make the reader ache as they get to know Keegan in greater and greater detail, as more and more of her personality is revealed and we realize how much has been lost.

This gradual recognition, though sobering, is addictive, and while the essays offer the sad pleasure of learning to mourn a someone, the fiction tempts readers to look for even more hints of Keegan in young characters, in situations and in settings. This is the constant danger of posthumous reading, or of any biographically motivated reading – that we look too hard, imagine hints of memoir where there is only fiction, and in so doing trample everything that makes fiction unique and powerful. This is doubly dangerous when reading The Opposite of Loneliness, where the drama of the collection stems in no small part from biographical tragedy.

Reading the collection’s stories as nonfiction is particularly tempting when the narrating characters resemble Keegan in age and situation. “Cold Pastoral” presents this possibility, as does the next story, “Winter Break.” Both feature narrators who resemble the persona Keegan assumes in her essays – all three are young women in college who are working out relationships with friends, family, and themselves. But then there are stories where one would really have to strain to see Keegan’s shadow – a series of emails from an engineer in Baghdad; a scientist trapped in a powerless deep-sea submarine – and these seem slightly clumsier, more like student writing and less grounded in experience and believable voice. They are flat, and lack the sparkle that sets her other writing apart from that of most other 22-year-old English majors. Part of this may be the inherent difficulty in imaging and representing full adult lives when one is 22, still straddling adolescence and adulthood. Part of this may be the reader grumbling that there is no great drama here, no personal details that can make us hurt for the loss of Keegan. To that reader (and to myself) I repeat Anne Fadiman: remember her because she’s good, not because she’s dead.

But how good is she, really? It’s difficult to say because it’s difficult to know who to compare her to. Outside of small literary magazines there aren’t many voices as young and modern as Keegan’s who are finding publications and readers, and even in those magazines there are few stories about being 19, 20, 21, about trying to grow up in an uncertain moment, in an uncertain generation. “Every generation thinks it’s special,” writes Keegan, but it’s difficult to say right now just how special ours is, much less how special we will be.

What I can say is that I have met and read many young writers who, like Keegan, are fascinated by social media and the new ways we communicate with each other. In my creative writing workshops I have read stories about searching for friends on Facebook, about discovering quinoa, about being a waitress in terrible restaurants during school breaks. I have read essays about the stress of marrying young and of staying single, about being uncertain about our jobs, about being uncertain about everything, about being afraid of dying, about wanting to be talented and original and a writer but feeling like we don’t really know how. YouTube videos are mentioned casually and relevant HBO shows are referenced. We go to house parties; we worry about our relationships; we keep detailed journals but we also write blogs. And this Millennial generation of writers can learn from Keegan in that she allowed herself to sound and to be fully 22, exactly who and what she was, to explore what that meant and to celebrate the value of a young perspective, no matter how uncertain, but never sounded like she was writing a generic think-piece on “What It’s Like to Be Young Today.” Her writing is marked by all the traits of modern youth but also tackles themes that have been present in great writing for centuries – love, fear, loss. That’s a balance I want us to achieve, what I think we should be working for, and if every young Millennial writer can strike it with the same authenticity of voice that she achieves then our literary generation will be one to watch. As Marina Keegan said, “Let’s make something happen to this world.”