Jesse Ball’s novel The Curfew is described as a dystopian father-daughter tale set in an unnamed city of the future where music is outlawed. It’s a quick and engrossing read—not nearly as sci-fi as that description suggests. The story follows William Drysdale and his daughter, Molly, as they adjust to life in a world where people just disappear without explanation, including Molly’s mother. There are revolutionaries who tell William that they know what happened to his wife, but he must sneak out to meet them and risk his life by staying out past the strictly enforced curfew.

Jesse Ball’s novel The Curfew is described as a dystopian father-daughter tale set in an unnamed city of the future where music is outlawed. It’s a quick and engrossing read—not nearly as sci-fi as that description suggests. The story follows William Drysdale and his daughter, Molly, as they adjust to life in a world where people just disappear without explanation, including Molly’s mother. There are revolutionaries who tell William that they know what happened to his wife, but he must sneak out to meet them and risk his life by staying out past the strictly enforced curfew.

Ball, also a poet, writes in lyrical prose that is never cryptic or overly descriptive. His previous work includes Samedi the Deafness (2007), The Way Through Doors (2009) and the story “The Early Deaths of Lubeck, Brennan, Harp & Carr“, which won The Paris Review’s Plimpton Prize in 2008 and is highly disturbing and wonderful. His writing is often called minimalist, because the paragraphs are short, the dialogue isn’t punctuated with quotation marks, and unnecessary descriptions are cut. But it isn’t minimal in emotion or imagination.

Ball, also a poet, writes in lyrical prose that is never cryptic or overly descriptive. His previous work includes Samedi the Deafness (2007), The Way Through Doors (2009) and the story “The Early Deaths of Lubeck, Brennan, Harp & Carr“, which won The Paris Review’s Plimpton Prize in 2008 and is highly disturbing and wonderful. His writing is often called minimalist, because the paragraphs are short, the dialogue isn’t punctuated with quotation marks, and unnecessary descriptions are cut. But it isn’t minimal in emotion or imagination.

The Curfew is divided into three parts that flow into each other the way a dream wanders and evolves, finally leaving you awake, wondering what it all meant.

When I learned that Ball teaches a course on lucid dreaming at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I was eager to speak with him about how you teach someone to take control of her dreams and what that has to do with writing. While our phone conversation seems to range from chess hustlers to dream yogis, it reveals a writer who is driven by a fervent imagination and inspired by the power of storytelling.

The Millions: I read a review online and the writer asks, “What on earth is this book about?” so that’s what I’ll ask first.

Jesse Ball: We’re all put in to difficult circumstances in our life and we have to decide how we can create our own life within that, so I think the core of the book is about how a family can create interior circumstances or render inconsequential whatever difficulties the world forces on them.

TM: What was the first idea for the book, did you want to write about the father-daughter relationship?

JB: The first idea was actually the strategy that the revolutionaries are employing to try to defeat the government. That was the germ of the idea.

TM: So it was political in origin?

JB: I generally am a person who loves games, and strategy, so it was more of an abstract exercise in strategy.

TM: What kinds of games? Are you a chess player?

JB: I love chess. I spend much too much time playing chess.

TM: Do you play online, or at the park?

JB: I play at parks. I used to play at Washington Square Park.

TM: Those guys are amazing, but they’re hustlers. Did you ever get hustled?

JB: In chess you can kind of tell who’s better than you and who you’re better than. There’s a range of hustlers with different abilities. So you can show up with 20 bucks, or 40, 50 bucks—however much you want to use—and play some guys who you think you can beat, and you can take their money, and then you can play the other ones who are better than you and sort of give it back.

TM: Do you decide how much to bet before you play?

JB: You look around, see who’s playing, and check out the different abilities of the guys. It’s not always ironclad when you’re watching that a person is playing as well as they can. Some people can give a good hustle so they play badly at first and lose on purpose, and then win in the long run. In athletics I think it’s easier to play badly on purpose. But in chess usually you can tell how good a person is—sometimes just by physical mannerisms. One of the first giveaways is, if you’re about to play chess with somebody, mess up the pieces so that they have to reset them, and when you watch them setting up the pieces you can see the physical dexterity with which they handle the pieces, and that will tell you how good they are at speed chess.

Then you sit down, and first you ask if the person is going to pay the winner. Some people will just act like you’re going to pay them to play. Then even if you win, you won’t get paid. So first make sure you’re going to get paid. The second thing is to decide how much. Two dollars a game, three dollars a game, five, or more.

TM: What’s the most you’ve ever bet?

JB: I played a $50 game once.

TM: Did you win?

JB: Yes. Although I’d lost the three or four previous games, so it came out even. I just want to come out even.

TM: Your author biography says, “He is an assistant professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and teaches classes on lying, lucid dreaming, and general practice.” What does that mean?

JB: There are different ways to get better at writing. You can improve the technique, you can change the content of what you write, and you can change the general organization of your thought. Most of teaching writing revolves around fixing technique. I think that that’s okay. But to me, most of the issues that a person has with technique will automatically be fixed by reading a lot of good books and by doing a lot of writing. Even though it might take ten years, those things will be fixed. The thing that I think that’s a better path to becoming good is to work on those other things—the content, to find things you love to write about, and then to become sharper and clearer at thinking. So my class—the classes on lucid dreaming, on lying, or walking—those make people live better, more interesting lives and then whatever they write will be better.

TM: What would be a typical lesson plan for your lucid dreaming class?

JB: There’s been a lot of research done about lucid dreaming. Lucid dreaming is the quality a dream has when you become completely conscious and you can control what happens in the dream. There have been Tibetan dream yogis who have done lots of work on this, and there’s a guy named Stephen LaBerge who wrote a number of books that are really wonderful about lucid dreaming. I model my course on some of his methods. The attempt is to make it so the students will be able to lucid dream by the end of the course. I’ve been pretty successful. I taught it a couple of semesters ago and I’m teaching it in the fall.

TM: Do the students keep a dream journal?

JB: It is one of the things, yes. Many of the techniques have to do with establishing habits, which you establish in your daily life so that the habit will occur in the dream. For example, every time you cross a threshold—a doorway, putting your head out of a window, getting out of a car—you force yourself to stop for a second and ask yourself if you’re dreaming.

Then hopefully in your dream anytime you cross a threshold the habit is so engrained as a part of your personality that you then in the dream say, “Am I dreaming?” and the answer at that point is yes. But it’s more complicated than that because in the dream you don’t think that you’re dreaming. So you need to have a test within the dream to establish whether you’re dreaming or not.

There are a number of different tests. Any kind of digital numbers get messed up. If there’s a clock on your wrist that has a digital read-out, you look at it, look away, then look back and if it’s all messed up, you know that you’re in a dream. Text in general doesn’t tend to stay the same. So you cross a threshold in the dream, and you say, “Okay, am I dreaming?” Then you look around and try to find some text, look at it, read it, look away, look back and it will likely have changed.

TM: So once you have that knowledge, that the dream is a dream, what’s the point?

JB: At that point, you can fly around….

TM: You have complete control.

JB: Absolutely. You can make a gigantic whale jumping out of the water.

TM: What was the last lucid dream that you had?

JB: I had one a few weeks ago. But in the fall I’ll be doing it a lot. I try to do the exercises along with the class. I had a friend who was obsessed with recording his dreams. It’s a world that expands the more you get into it. So he was recoding his dreams every night, and every morning he would wake up and write for five minutes. Eventually it got to be that it was taking an hour and half to record all of the dreams he was remembering. So he had piles and piles of notebooks. For me, being able to focus on the dreaming and recording it depends on my stepdaughter, who is going to be 12 in August. She has to get ready and go to school, so the morning time gets messed up.

TM: I can completely see the effect of this in the book, because it had such a dream-like quality. It’s imaginative in the way that in a dream some things don’t seem logical or normal but you accept them as true (for the duration of the story). That’s how The Curfew was for me. The main character’s job is an epitaphorist (he writes epitaphs on gravestones); did you make that up?

JB: I did. I’ve always been obsessed with cemeteries, and I think it’s a good thing to put things in your book that you love. I saw the dramatic possibilities of the profession. Many people’s day-to-day work might be really interesting, but just showing one day of that might not be so interesting. For some people, what they’re doing is completely fascinating, but just one day would be enough. In this case it’s a profession where I can give these little encounters, each one is a kernel.

TM: I think the structure of your book is very interesting; I read it all in one night and I was trying to figure out why the pages went so quickly. Some pages are just one giant word.

JB: That’s one thing that I prize. The reader should be able to ingest the material whole, and they instinctively know what to do with it. What’s actually going on at the moment [in the story] should be very clear. Sometimes people will talk about my books as being experimental, but they’re not. They might appear to be experimental because they look a little different, but they’re quite old-fashioned especially in the responsibilities I take in regards to telling the story. I think that the responsibility that the storyteller has in reaching the audience is an ancient one, and is very important. What I want is to make a path through the tale so the reader can fly through it, and maybe not get everything the first time, but get enough just by virtue of passing through. I want all the details to fall into place. I think transparency is always good.

TM: So is it the narrative that drives your writing or is it something more theoretical?

JB: [The Curfew] is a manual about how to live in a difficult time.

TM: But then the answer is to escape. The last part of the book is a puppet show, an escape into fantasy to avoid reality.

JB: In some ways it could be deemed as escape, but it’s also her way of grappling with and overcoming the events. She’s making up an account of the times, in the time. And that’s something important—for people to have a historical sense and take the facts of what they see and put them together for themselves—take that responsibility. Too many people let someone else see the work and say what happened.

TM: Her control over the puppet show, and writing the script, is like your lucid dreaming, you get in there and you take control.

JB: Absolutely. Also there are so many things she remembers from her childhood, and in the dream you’re not only supplied with the current context of where you are, but you remember a whole bunch of memories in a dream.

TM: Your website is very fun and interactive. It kind of reminds me of the book because you first think, “What is going on here?” And then you just accept it and enjoy it.

JB: There are different philosophies for how to make a website. There are basic ideas about entertainment. Whether a person should be allowed to always be deciding what will entertain them or how they will be entertained, or whether the person will make themselves subjective to entertainment that then whisks them off their feet—then at the end they enjoyed it or didn’t. I think we have so much of that first kind—always in control of how you’re being entertained—that I think a little bit of the other kind is good. The website is definitely of the latter camp.

TM: You said earlier that you have a stepdaughter. Do you get a lot of practice telling her stories?

JB: Yes. I first met her when she was five. I was telling her a story one day and I was completely inspired and taken aback and shocked by the power a story can have over children. When you’re used to adults, and reading to adults, the best you can get is 50 or 60 percent of their attention. It makes it hard to powerfully emote, and become totally dedicated to that storytelling moment if you’re not getting the energy back. I was telling her the folktale of the frog and the scorpion. The scorpion is at the river and he wants to cross. He sees a frog there so he asks him to ferry him across on his back and the frog says, “No, you’re a scorpion! You’re going to sting me!” And the scorpion says, “No! Why would I do that? We would both drown!” The frog says, “You’re right, I’ll carry you across.” So they get about halfway across and the scorpion stings the frog, and as they both sink the frog says, “Why did you sting me!” and the scorpion says, “Because I’m a scorpion!”

TM: What was her reaction?

JB: When the scorpion stings the frog and the frog starts sinking, she burst out crying, powerful convulsive tears, so intense. She probably felt that she was the frog, and felt that she was the scorpion. I found that very inspiring, because it’s not just for children—you can reach adults that way, but it has to be delicately. You have to get them to forget they’re adults.

TM: Do you get a lot of feedback from your students about your books?

JB: They’re usually pretty happy about the whole thing. They might be too kind.

TM: Because they’re trying to get a good grade? How do you get graded in lucid dreaming?

JB: Well the class is pass/fail. The main thing is you have to write a manuscript later. I don’t have to grade their grasp of dreams with a D or an F.

TM: Are you working on anything new?

JB: I have another book coming out in July. It’s an omnibus with two books of poetry, two books of short prose, and two novellas, all condensed into this small, pocket volume that you could take on the train. It’s by Milkweed publishing, called The Village on Horseback.

See Also: The Three Worlds of Jesse Ball’s The Curfew

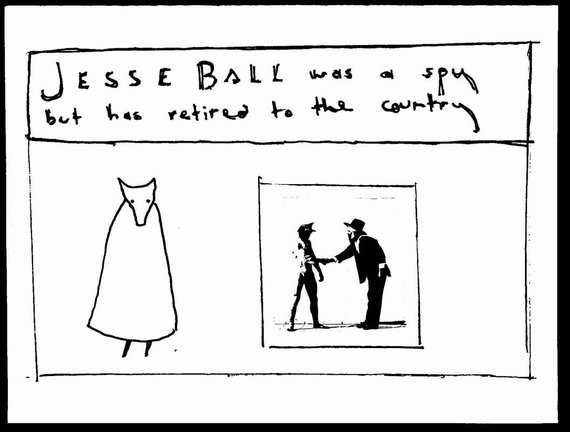

(Image from jesseball.com)