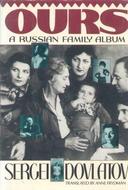

This is going to have to be quick and dirty, because my library copy of Sergei Dovlatov’s Ours: A Russian Family Album is already five days overdue—already twice renewed, and with two holds requested (my sincere apologies, ye law-abiding library patrons!). It is the single circulating copy at the New York Public Library. A search of two other library systems, a multi-county system upstate, and a major university, yielded just one copy, which is unavailable until February 2010, held by the university.

This is going to have to be quick and dirty, because my library copy of Sergei Dovlatov’s Ours: A Russian Family Album is already five days overdue—already twice renewed, and with two holds requested (my sincere apologies, ye law-abiding library patrons!). It is the single circulating copy at the New York Public Library. A search of two other library systems, a multi-county system upstate, and a major university, yielded just one copy, which is unavailable until February 2010, held by the university.

At Amazon, used copies from partner sellers are going for $24.39 – $139.22, and the three new copies go for $83.99, $101.59, and $141.13. There are no English translations of Dovlatov’s books currently available for preview on Google Books. The English language hardcover was originally published by Weidenfield & Nicolson in 1989; shortly after, in 1991, W&F was acquired by Orion, who was later (1998) acquired by France’s Hachette Livre. Needless to say, the book is out of print.

This is a terrible state of affairs. Dovlatov himself, whose literary success came so belated, and whose life and work were born of thwarted aspirations, dark comedy, and totalitarian absurdity, may have shrugged his shoulders: par for the course. He was a great humorist, and if he were with us today (he died in 1990), he would certainly find it amusing that a copy of his slim, “trifle” of an autobiographical story collection could sell on the American market for over $100. And yet, if you ask me, 100 bucks for a fresh, all-mine copy of Ours, might just be a bargain.

Sergei Dovlatov was born in the Republic of Bashkiria in 1941 but spent most of his childhood and pre-émigré adult life in Leningrad (St. Petersburg). He was a university flunky, worked as a prison guard in high-security camps for the Soviet Army, then eventually scraped together a living as a minor journalist in Leningrad and Estonia. He failed to publish his creative work in Russia, but began to find an audience among Russians in the West beginning in 1976; after which, a period of intense harassment by Soviet authorities, including expulsion from the Union of Journalists, ensued. In 1978, he emigrated to Forest Hills, NY. He published 12 books in the US and Europe, including The Suitcase, The Zone, The Compromise, A Foreign Woman, and Ours. His work was finally published and recognized in Russia following his death (after the fall of the Soviet Union). The New Yorker published nine of his stories—one published as nonfiction—between 1981 and 1989, five of which are collected in Ours.

Sergei Dovlatov was born in the Republic of Bashkiria in 1941 but spent most of his childhood and pre-émigré adult life in Leningrad (St. Petersburg). He was a university flunky, worked as a prison guard in high-security camps for the Soviet Army, then eventually scraped together a living as a minor journalist in Leningrad and Estonia. He failed to publish his creative work in Russia, but began to find an audience among Russians in the West beginning in 1976; after which, a period of intense harassment by Soviet authorities, including expulsion from the Union of Journalists, ensued. In 1978, he emigrated to Forest Hills, NY. He published 12 books in the US and Europe, including The Suitcase, The Zone, The Compromise, A Foreign Woman, and Ours. His work was finally published and recognized in Russia following his death (after the fall of the Soviet Union). The New Yorker published nine of his stories—one published as nonfiction—between 1981 and 1989, five of which are collected in Ours.

Why is Dovlatov so little known or read in the West today? Fiction Editor Deborah Triesman asked David Bezmogis this question on a New Yorker podcast. “I have no idea,” he said. “It’s hard to understand these things.” Dovlatov couldn’t have said it better himself.

Ours is composed of 13 stories, each about a different Dovlatov family member (the collection was published as fiction but is quite evidently based on Dovlatov’s real-life family). There is Grandpa Isaak, a Jew of enormous physical stature, who was mysteriously arrested for espionage and killed in a prison camp; Grandfather Stepan, an Armenian Georgian, who threw himself into a ravine; Dovlatov’s bastard cousin Boris, handsome and talented, who courted danger and whom “life turned into a criminal”; Uncle Leopold, a “hustler,” who disappeared from their lives for over 30 years before being rediscovered in Belgium. Mother and Father, an actress and a theatre director, “often quarreled,” and divorce when Dovlatov is eight years old. And of course there is Lena (pronounced “Yenna”)—more on Lena later—Dovlatov’s wife, who emigrates with their daughter Katya years before Dovlatov joins them. In the opening of the story that describes their courtship and marriage, the narrator Sergei Dovlatov tells us, “I emigrated to America dreaming of divorce.”

Would you guess that Ours is essentially a comedy? The humor is exhilarating, in a specific way that I find hard to describe. It’s likely there is something that Russians who experienced the Stalinist and Soviet eras first-hand recognize as “Russian humor,” and as a Westerner I am just an enthusiastic tourist, smitten by an approach to the terrors and darkness of life that is both sharp and silly. I suspect my receptiveness to Dovlatov is also related to a bit of miserable-family-memoir fatigue. A quick perusal of the memoir section of a bookstore (McCourt, Karr, Walls, Burroughs, Pelzer, et alia—all fine and important writers, no argument there) might illustrate for you what I mean.

Dovlatov has plenty to boo-hoo about. Instead, Stalin appears as an unnamed throwaway understatement here and there (“Under dictators, people who stand out do not fare well”), major socio-political eras are summarized briskly (“The country was ruled by a bunch of nondescript, faceless leaders…On the other hand, father would point out, people were not being shot, or even imprisoned. Well… yes, but not so often”), the “savageness” of Russia deflected from a story’s main focus by a line like, “I’m afraid I couldn’t explain it. Dozens of books have been written about it.” On the subject of his own arbitrary imprisonment, Dovlatov again deflects (“Then I was suddenly arrested and put in Kalyaevski prison. I don’t much feel like writing about it in detail. I’ll say only this about it: I didn’t like being in jail”), in this case the story being about Mother, you see, not about Soviet repression; about, in particular, her “ethical sense of spelling” (she was a copyeditor), her cheerleading when he finally became published, and about how “we’ll never part.”

But I was telling you about Dovlatov’s comic talents. The thing about laughter is that it is most real, most soul-cleansing and invigorating, when it begins and ends in tears. “Ka-a-kem!” Grandfather Stepan shouts at his relatives for trying to convince him to leave his own home because of an earthquake warning. “I crap on you!” Does anyone else think that this is the most hilarious thing ever to shout at your relatives moments before a devastating earthquake? After the quake passes, hundreds of buildings collapsed and the water supply destroyed, Stepan’s wife finds him sitting in his armchair amid the rubble and laments, “The Lord has left us without a roof!” Stepan’s response? “‘Eh-eh.’ Then he counted the children.”

And then there’s this dialogue exchange, between Dovlatov and the German proprietor of a hotel in Austria, where Dovlatov and his mother await permission to enter the US as émigrés (the German speaks first):

“Did you ever belong to the Party?”

“No. In my opinion, the Party should consist of one person.”

“That’s the truth. What about the Young Communist League?”

“Yes. That happens automatically.”

“I understand. How do you like the West?

“After prison I like everything.”

“My father was arrested in 1940. He called Hitler ‘das braunes Schwein.’”

“Was he a Communist?”

“No… He wasn’t a Commie. He wasn’t even red. He just stood out. He was an educated man. He knew Latin. Do you know Latin?”

“No.”

“Neither do I. Pity. And my children won’t know it either, which is a pity. I suspect Latin and Rod Stewart don’t go together.”

“Who is Rod Stewart?”

“A madman with a guitar. Would you like a glass of vodka?”

“I would.”

“I’ll bring some sandwiches.”

“Not essential.”

“You’re right.”

Also entertaining are Dovlatov’s wry self-deprecations regarding the writer’s vocation. “Do you have any sort of profession?” Uncle Leopold, the long-lost rich businessman in Belgium, asks. With characteristic unconviction, he replies, “Mainly I’m a writer. I write.” Relating his mother’s history as an actress, he writes: “She chose to enter the theater institute. I myself think it was the wrong choice. Generally speaking, one should avoid the artistic professions.” Recounting the first writing competition he ever won, he says of the two co-winners: “In his more mature years, Lenya Dyatilov took to drink. Makarov became a translator of the languages of the Komi people.” Then, “As for me, it’s never been clear, exactly, just what my occupation is.”

There is the story about Glasha, the family’s fox terrier, who went off with a family acquaintance into the Siberian forest for a few months to be trained as a hunting dog, and about whom Dovlatov’s mother eventually says, “It’s boring without Glasha here. There’s nobody to talk to.” Glasha turns out to be a “born nonconformist” and thus makes the journey with Dovlatov and his mother to New York, where it becomes evident that she has “little talent for democracy,” and is “loaded with neuroses. The sexual revolution never touched her. A typical middle-aged woman émigré from Russia.”

It’s not all fun and games, of course. Again, we understand better than we ever have as we read Ours that the heart of the best literary comedy is tragedy. Aunt Mara, a well-known literary editor, was privy to the ugly undersides of many famous Russian writers—political betrayals, spousal violence, felonious historical revisionism, petty crime. “My aunt knew a great many literary anecdotes… But what my aunt remembered for the most part were the humorous instances. I don’t fault her for this. Our memory is selective, like a ballot box.”

In the collection’s most explicitly political story, “Uncle Aron,” we get “the history of the Soviet Union itself.” Dovlatov’s mother’s younger brother switches loyalties and affiliations like Facebook profile pictures—first adoring Stalin, then becoming infatuated with Stalin’s successor Georgi Malenkov, then Nikolai Bulganin, then Krushchev. Eventually, he grows weary of disappointment and thwarted adoration, so he settles on Lenin, since he “had died long before and could not be removed from power…This meant the love could not decline in value.” Dovlatov quarrels often with his uncle, over the brilliance and/or idiocy of communism, until Uncle Aron falls ill, and in a fever of despair says to his nephew: “Do you know what torments me? When we lived in Novorossisk there was a fence—a tall brown fence—near our house. I walked by that fence every day. And I don’t know what was behind it. I never asked. I didn’t think it was important. How senselessly and stupidly I’ve lived my life!” Uncle Aron gets well again, but then gets sick, then gets well again; the two continue to quarrel. “I was very attached to him,” Dovlatov writes. Uncle Aron eventually grows old: “Then my uncle actually did die. A pity, and that tall brown fence gives me no peace.” Such a benign image, and yet it gives us no peace, either; we too are haunted by what’s hidden in the quotidian, our failures of perception, our deadened curiosity.

The penultimate story in Ours, and arguably its emotional center, is the story about Dovlatov’s wife Lena, “The Colonel Says I Love You.” It’s the only story not named for its main character, and once you’ve read it, you’ll recognize that it couldn’t be any other way; that the character Lena is so enigmatic, so compellingly unknowable, that to call the story “Lena” would be as flat and off-pitch as calling Ours, simply, “funny.”

But it is funny. And God knows we need funny, real funny, heartbreaking after-prison-I-like-everything funny. In defense of my habit of staying up late for Craig Ferguson, I found myself saying to my sleep-deprived life mate (it’s a studio apartment), as authoritatively as if I held an M.D. in funny, “You have to laugh out loud, from your lower belly, at least once a day.” Coming around again to the question of why Dovlatov is so little read today, David Bezmogis could only offer further perplexity: “He is so current, if we look at things that are popular now… my God, if he were published today, he’d be on the bestseller list, like… the Russian David Sedaris.”

Godspeed in claiming your copy of Ours. Hurry, while supplies last.