In January 2003, Norwegian journalist Asne Seierstad arrived in Baghdad on a 10-day visa. With arrangements in place with various Scandinavian print and television media, the freelancer joined the growing ranks of international press who wanted to witness the changes that were in the air. Well, ten days grew to twenty and eventually to a-hundred-and-one. When she finally left, in April 2003, one type of hell had been replaced by another.

In January 2003, Norwegian journalist Asne Seierstad arrived in Baghdad on a 10-day visa. With arrangements in place with various Scandinavian print and television media, the freelancer joined the growing ranks of international press who wanted to witness the changes that were in the air. Well, ten days grew to twenty and eventually to a-hundred-and-one. When she finally left, in April 2003, one type of hell had been replaced by another.

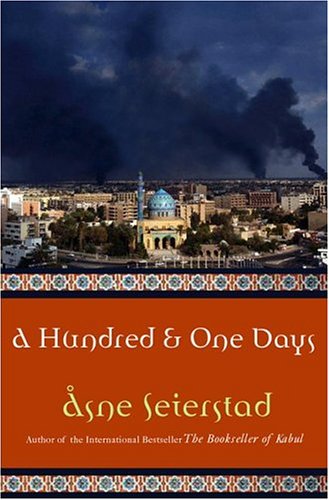

Out of all this comes A Hundred and One Days: A Baghdad Journal – a powerful bit of reportage that chronicles not only the thuggish brutality of Saddam’s regime and the heart-wrenching civilian “casualties of war” caused by the chaotic “Shock and Awe” invasion, but also a gripping behind-the-scenes account of war-journalism which at times plays out like a thriller.

When she first arrives, its still Saddam’s show. We see Seierstad working her way through the red tape of the Iraqi Ministry of Information. It seems so much like Soviet-style media control that at times I feel like I’m reading an account of a Western journalist in Cold-War era Moscow. When Seierstad eventually gets the chance to meet people in Baghdad it’s always with an official “minder” and the answers she gets are almost always stock answers. These people are afraid. Saddam had instituted a form of domestic terrorism, putting fear into the lives of Iraqis. Even the odd time that Seierstad escaped the watchful eye of her “minder,” responses from some citizens showed just how Saddam’s cult of personality had indoctrinated them. Saddam was everywhere. Posters, statues, all art glorified this megalomaniac. Seierstad also chronicles the poverty under his regime. The wars with Iran and Kuwait, the first Gulf War, and the ensuing Western sanctions had crippled the country.

But it was early 2003 and something was in the air. Whatever line the Ministry of Information was giving, everyone knew the US invasion was imminent. The closer they got, the more Saddam’s regime lost its grip. The reins of government slackened and when Seierstad sneaks out to interview people, they begin to speak a bit more freely, more candidly. Feelings were mixed. The US invasion, just days away, was alternately feared and anticipated, often in the same breath. The common thread through most of the civilian responses was “Well the US is coming, let them sweep Saddam and his regime away and then leave, immediately”. Given the hell they’d been living through, no one could be surprised by this kind of resigned-optimism. And given the nature of war, no one can really be surprised that this optimism was shattered.

Seierstad’s eye for detail is remarkable. At one point, on the eve of the invasion, she goes to an open-air book market. At that point, it had been a dozen years since the last scientific periodical was available in Iraq, but the Iraqis’ thirst for knowledge was unquenchable. There was a boy looking for a book about cloning, and a man seeking any book he could find about structuralism. Another was searching for Sartre. The insatiable quest for scientific knowledge and artistic enlightenment, especially through periods of brutality and oppression, has always been, to me, humanity’s saving grace.

Seierstad also shows how the “human shield,” that collection of activists who flocked to Baghdad to physically oppose the US invasion, wound up becoming a tool of the Iraqi regime. While the Shield-ers wanted to protect hospitals and orphanages, the Iraqi government instead used them, co-opted them, by placing them in front of Iraqi infrastructure. They became pawns.

Free of the lures and pressures of being an embedded journalist, and providing a clear-headed Scandinavian reasonableness to a chaotic situation, Seierstad’s account is unique. And as a Western woman trying to maneuver independently in a Middle Eastern country, even one which is admittedly more tyrannical than fundamentalist, Seierstad’s compelling tale becomes a worthy addition to modern reportage.