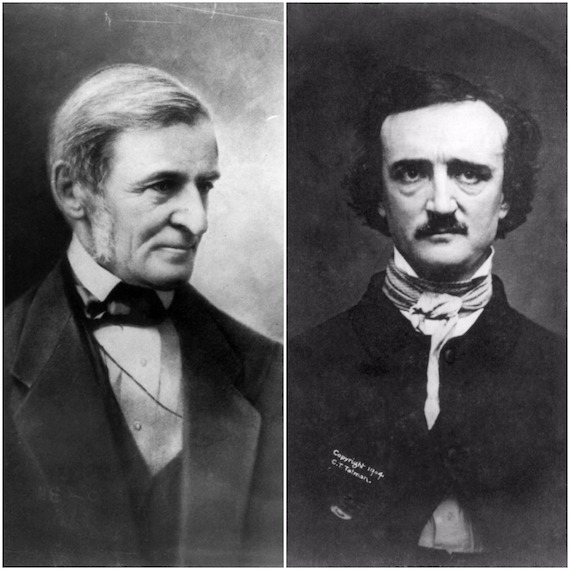

It’s hard to imagine two more different temperaments than those of Edgar Allan Poe and Ralph Waldo Emerson, contemporaries who, even in their own lifetimes, were conceived in opposite terms: darkness and light, illness and health, extreme depression and unbridled optimism, self-destruction and self-affirmation. Emerson was thought to be an emblem of America the Symbol: America the new birth of freedom, the unlimited frontier of possibility. But Poe’s surreal, claustrophobic, and weirdly rationalistic American Gothic, his world of vice, madness, and murder somehow put into motion by dark applications of reason, depicts an America that is no less real than Emerson’s, though also no more real.

Poe was a well-known literary critic, but not so well-known that Emerson — the most famous and beloved American literary figure of his day — couldn’t afford to ignore him. He did take enough time out to dismiss Poe — no doubt on the basis of “The Raven” — as a “jingle man.” Like many of the literary lights of the time, he probably regarded Poe as tasteless. For his part, Poe regarded Emerson, with “reverence,” as extremely tasteful, and boring in his tastefulness: “It is Taste on her death-bed — Taste kicking in articulo mortis.” Poe portrayed himself as an enemy of the Transcendentalists at least to the extent of often sneering at them. He called Emerson “over-rated” and remarked on the lack of basic logic and rationality in his philosophy.

Poe opposed the Transcendentalists’ brand of abolitionism and their individualism; he thought they were derivative, harboring plagiarists (Poe saw plagiarism everywhere) and thought Emerson himself a pale imitation of Thomas Carlyle; he sneered at their apparent unanimity, and thought of Concord, Mass., as a nest of overvalued mediocrities. He asserted that Nathaniel Hawthorne was the best writer in America, but urged him, hilariously yet violently, to get the hell out of Concord: “Let him mend his pen, come out from the Old Manse, cut Mr. [Bronson] Alcott, hang (if possible) the editor of ‘The Dial’, and throw out of the window all his odd numbers of ‘The North American Review.'”1

Here is a typical sally of literary brutality directed at Transcendentalist Margaret Fuller and fellow travelers Cornelius Mathews and William Ellery Channing.

Miss Margaret Fuller, some time ago, in a silly and conceited piece of Transcendentalism, which she called an “Essay on American Literature,” or something of that kind, had the consummate pleasantry, after selecting from the list of American poets, Cornelius Mathews and William Ellery Channing, for especial commendation, to speak of Longfellow as a booby, and of [James Russell] Lowell as so wretched a poetaster “as to be disgusting even to his best friends.” All this Miss Fuller said, if not in our precise words, still in words quite as much to the purpose. Why she said it, Heaven only knows — unless it was because she was Margaret Fuller, and wished to be taken for nobody else. Messrs. Longfellow and Lowell, so pointedly picked out for abuse as the worst of our poets, are, upon the whole, perhaps, our best — although [William Cullen] Bryant, and one or two others are scarcely inferior. As for the two favorites, selected just as pointedly for laudation, by Miss F. — it is really difficult to think of them, in connexion with poetry, without laughing. Mr. Mathews once wrote some sonnets “On Man,” and Mr. Channing some lines on “A Tin Can,” or something of that kind — and if the former gentleman be not the very worst poet that ever existed on the face of the earth, it is only because he is not quite so bad as the latter. To speak algebraically: — Mr. M. is ex ecrable, but Mr. C. is x plus 1-ecrable.

Not only does this skewer Fuller’s so-Emersonian individualism, but it is written in a style that no Transcendentalist could ever have countenanced: diabolical literary homicide, a darkly hilarious twisting of the blade, redolent of hostility and delight in negation. The Transcendentalists were quite relentlessly affirming. We might compare, from a century later, John Dewey vs. H.L. Mencken: the inspiring optimist and the withering uproarious cynic.

Really, no Transcendentalist could have written anything that Poe wrote, at least until the very end of Poe’s authorship, as we’ll see. He was at once more rationalistic and more pathological than any of them. It is a remarkable combination: surreal psychological horror paired with the remarkably clear deductions of Poe’s detectives, scientists, cryptographers, and even of his murderers. His darkest characters examine themselves rationally as psychological case studies. The Transcendentalists wrote to bring light and hope to the world; Poe showed that light makes shadows.

Emerson conceived human beings as fragments of a perfectly good God. The following is quite characteristic:

As a plant upon the earth, so a man rests upon the bosom of God; he is nourished by unfailing fountains, and draws, at his need, inexhaustible power. Who can set bounds to the possibilities of man? Once inhale the upper air, being admitted the absolute natures of justice and truth, and we learn that man has access to the entire mind of the Creator, is himself the creator in the finite.

Poe’s view of human nature was quite a bit more….complex. In the crypto-scientific paper/tale of murder “Imp of the Perverse,” he asserts that one of the basic human impulses is to do compulsively what is against what is demanded of us, or against our own commitments, or against our own interests. “We act,” he writes, “for the reason that we should not…I am not more certain that I breathe, than that the assurance of the wrong or error of any action is often the one unconquerable force which impels us.” I imagine the saint and sage of Concord reading that and not knowing what the hell the man was talking about.

But of course the yin-yang is a symbol of the interdependence of opposites. At the center of the light is a seed of darkness, and at the center of the darkness a seed of light. Both Poe and Emerson faced the loss of beloved wives (Ellen and Virginia, respectively), Emerson also of his son Waldo. Poe endured the death of almost everyone he ever loved. I think it is not necessarily what they experienced that accounts for the difference of their philosophies, though overall Emerson had the easier road in life (few writers have ever had a harder road than Poe). I think, rather, their respective writerly personae represent what they were as human beings before they ever wrote anything for publication, and embody the strategies they developed to deal with their own suffering: transcending it with hope, or facing it in its every dark twist. In both cases, the intrinsic temperament became a picture of their own nation and of the whole universe.

Indeed, Poe’s last major work was a very serious theory of everything: the ‘prose poem’/story/essay Eureka, in which he advocates — quite as Emerson might have — an understanding of the universe based both on the latest science and speculative acts of poetic intuition. He proves the efficacy of this technique, at least as applied by himself, giving what I believe is the first clear statement of the idea of big bang, and a picture of the universe as undergoing cycles of expansion and contraction from a “primordial particle” and back again, under the influence of gravity. Characteristically, he thought the universe is now in its collapsing phase, but uncharacteristically he ecstatically understands the collapse as a unification of all things, all spirits, all bodies, all oppositions, into oneness, and into God. He says that we are fragments of the Divine, being pulled by gravity into unity.

And he leaves us with this, after all that terror, self-loathing, and loss: When “the universe of stars” again becomes a singular point, the “myriads of individual Intelligences” will be “blended into One.”

The sense of individual identity will be gradually merged in the general consciousness — [and] Man, for example, ceasing imperceptibly to feel himself Man, will at length attain that awfully triumphant epoch when he shall recognize his existence as that of Jehovah. In the meantime bear in mind that all is Life — Life — Life within Life — the less within the greater, and all within the Spirit Divine.

It could have been written by Emerson.

1. [The Old Manse was Emerson’s childhood home in Concord, then being rented by the Hawthorne family. Bronson Alcott was the Transcendentalist educator and father of Louisa May. The Dial was the Transcendentalist periodical edited by Margaret Fuller and by Emerson himself. The North American Review was published in Massachusetts, perhaps enough to earn this bit of derision.]↩