Like most other art forms, fiction has undergone many configurations over the years, but its core has remained, as always, the aesthetic pleasure of reading. When we read, we connect to the immaterial source of the story through its outstretched limbs. The “limb” or variants of it are what the writer has deemed fit for us to see, to gaze at and admire. It is not often the whole. But one of the major ways in which fiction has changed today — from the second half of the 20th century especially — is that most of its fiction reveals all its limbs to us all at once. Nothing is hidden behind the esoteric wall of mystery or metaphysics.

The writers who do well to divvy up their fiction into fractions of what is revealed to the reader are the writers who tend to achieve transcendence, which, according to Emmanuel Levinas is recognized “in the work of the intellect that aspires after exteriority.” In fiction, a form of art expressed through letters, exteriority in this sense approximates meaning. For the writer endures himself to turn that which is interior inside out for the reader to see. Writing, then, is an act of turning out that which is in. The triangular writer then is he who projects meaning relentlessly yet systematically to the reader, and in the process of which readers glimpse something else. And then, something else. They see a man standing on the top of a cliff about to descend to his death, but they also see a cause — perhaps a nation’s communist past — standing there, about to plunge to its end.

When, in a text written more than 2,000 years ago, a character says, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up again,” the percipient reader hears at least two things: (a) In keeping with His miracles to this point, the said temple could be destroyed and this man, Jesus, can raise it up again with his miraculous power; (b) Once one has read to the end of the gospel of Matthew, one understands that “the temple” in fact means the man himself. It is he who will be killed, and he who will be raised again. This multi-layered meaning is, in the biblical concept, necessary because of the spiritual property of the book, and hence deemed “exegetic.” But the writers of triangular fiction achieve this in their fiction too. This is because the “divvying up” into fractions or parts that eventually become one and whole often works to more than one level of interpretation. The works of fiction that achieve transcendence are those works that lend themselves to this multi-layered interpretation.

I believe that fiction should work on at least three levels of interpretation: The personal, the conceptual, and the philosophical. In other words, the shape of the core of great works of fiction must be triangular — it must be emotional, cerebral, and sublime.

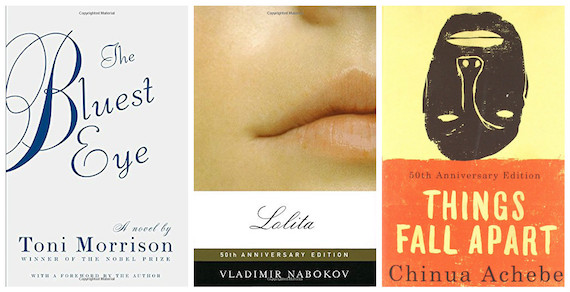

The personal level of interpretation is that basic level where the story meets the reader at his most human level. I will prop up three novels by some writers of this kind of fiction, Toni Morrison (The Bluest Eye), Vladimir Nabokov (Lolita), and Chinua Achebe (Things Fall Apart).

A young black girl in Jim Crow America who desires blue eyes. We know such a child has existed, and probably still does, and we cringe at the futility and even folly of such a desire. But we cannot deny its unvarnished humanness. A middle-aged man who has a crushing desire for a young pubescent girl whom he names his “nymphet.” We appreciate the humanness of his lust, and are disturbed/moved by it. Or a pre-colonial strongman of an Igbo village who has risen through hard times and established himself, his small kingdom, his traditions, and all that exist within the boundaries of his compound — and even beyond — “with a strong hand,” and then an encounter with a group of foreigners destroys all of that and brings him to become the lowest among his kinsmen, an akalaogoli, who cannot be accorded the common honor of a burial.

A young black girl in Jim Crow America who desires blue eyes. We know such a child has existed, and probably still does, and we cringe at the futility and even folly of such a desire. But we cannot deny its unvarnished humanness. A middle-aged man who has a crushing desire for a young pubescent girl whom he names his “nymphet.” We appreciate the humanness of his lust, and are disturbed/moved by it. Or a pre-colonial strongman of an Igbo village who has risen through hard times and established himself, his small kingdom, his traditions, and all that exist within the boundaries of his compound — and even beyond — “with a strong hand,” and then an encounter with a group of foreigners destroys all of that and brings him to become the lowest among his kinsmen, an akalaogoli, who cannot be accorded the common honor of a burial.

We can understand these characters and their stories as the writers, Toni Morrison, Vladimir Nabokov, and Chinua Achebe have created them on this personal level. But we can see, too, that much more lies behind these personal stories. The marigolds blossom, desire the bleak sun, and die, and in their protracted destinies share equivalent fate with Pecola. We see that the lust that fuels and drives Humbert Humbert, the lust in which he is imprisoned, is revealed in the thickets of language in which he is caught. But the aggregate meaning of the entire enterprise stretches beyond the page to the authorial intention expressed in the account of the monkey who, on being given a paper and pencil and taught the human art of drawing, draws the first thing in its mind: the bars around its cage. From this bar, its existence is enclosed and constrained. It cannot leave it. Its desire to leave comes and dies, unfulfilled, in futility, until it again surrenders to the reality that it will remain imprisoned. This is the distinct quality of the lust that possesses, and eventually destroys, Humbert Humbert and Lolita.

In Things Fall Apart, we can see, too, the ascension and power that Okonkwo acquires, and its flourishing when, at its peak, he receives various titles, and even has his daughter wedded. Then, an internal crisis erupts within him and slowly tears him apart. As he breaks down because Nwoye, his first son, has joined the ranks of the enemy, we also see — simultaneously — the villagers of Umuofia trying to understand what to do with their own brothers who have joined the white man’s religion and ways, causing the tribe to fall part. It is at this point that it becomes clear that Okonkwo isn’t merely an individual; he is Umuofia, he is an entire civilization, and it is not he alone but everything that falls apart.

The marigold, the monkey, the village of Umuofia — these become philosophical images on which these writers have constructed the personal stories of individual characters. On these things and on the vested characters, these triangular writers make profound philosophical statements while carrying through with strong, engaging plots. They are able to achieve this synchrony of vision because of the conceptual layer of their narratives. Morrison’s introspection into the head of her primary character is matched with an unblinking gaze from the outside through a girl her age, in Claudia. Thus, we are looking into Pecola, and looking at her at the same time. Humbert Humbert’s story is itself caged in bars. The writer within the story has died by the time the story is being published, and thus cannot change or touch anything in the manuscript. He cannot answer for anything that has been said, nor make restitution for anything that may require restitution. And within the precincts of the story itself, he is enslaved by an effusive, unguarded language as fecund as a wasteful forest, within which he himself gets lost. It is an imbroglio that yields, nonetheless, affecting flights of lyricism and ambient prose. And on the man on whom a poor beginning had been bequeathed, his rise is chronicled through a third person voice that intermittently strays into the omniscient. We see the knife that tears him within as it slides through the civilization of the Igbo people.

It is thus too difficult to not say, most definitely, that these three novels — The Bluest Eye, Lolita, Things Fall Apart —were conceived because their writers had diligently set themselves “the design of rendering the work universally appreciable” according to Edgar Allan Poe. Poe provides in that seminal essay that he had hoped to achieve this by seeking to “contemplate” the “beautiful,” a literary esotericism reached only by focusing on the effect of that which inspires beauty, and not the commodity of the beautiful itself. This is because “when indeed, men speak of Beauty, they mean, precisely, not a quality, as is supposed, but an effect — they refer, in short, just to that intense and pure elevation of soul…”

This is the trajectory by which writers of triangular fiction approach literary truth. For, in their works, that which is personal is at the same time a philosophy, and at the same time a conceptual/artistic conceit. And as we read, we can not help but notice the transcendent power of triangular fiction.