In this third episode of Swarm and Spark, a new literary column at The Millions written by an anonymous NYC editor and an MFA professor with the goal of restoring humanism to the literary conversation, we consider memoirs, crushing doubt, secrets, and shame.

Send in questions, comments, confessions, or complaints you would like to see answered, knowing your confidentiality will be equally assured, to swarmandspark@gmail.com.

Dear Swarm and Spark,

I’ve written a memoir which will be coming out from a major publisher in a few months. As with many memoirists, my life path has not been easy. I expose things in my book that most of my friends have no idea about. Throughout the editing process with my publisher, I’ve managed to calm down a lot and have come to accept that I’ve written this book for a reason and that I’ll just have to deal with whatever comes my way. That said, I do still wake in the night, in a panic, in a sweat, with crushing doubt. The world will know my secrets. The world will judge me. I feel completely overwhelmed most of the time but can’t let on, because I must maintain composure and be professional within this world of publishing. Might you have some words of wisdom for me? How do I deal with the exposure? How will I even speak about difficult topics while on book tour?

—Lucky Yet Fearful Debut Author

Teach: Lucky raises the great question that plagues so many: how does one ever overcome shame?

Editor: With honesty, I think; with belief that truth, however painful, is a curative. But it’s not easy. Do you think Lucky is more anxious about the reaction of her family or that of the outside world?

T: Maybe it is the projection of family onto the outside world. One of the most common reasons I’ve heard new writers cite for taking up the pen is the need to bridge a perceived divide between their experience of interior versus exterior.

E: That can be a painful process — but often one designed to curtail the erosive pain of lifelong trauma, trading compartmentalization for an integrated life.

T: But if you say honesty acts as an antidote to shame, does the greatness of art ever — or always — justify the human wreckage in its wake?

E: Well, I don’t think so — it’s a matter of balance, isn’t it? Privacy must be weighed against truth. But isn’t the cost of secret-keeping one of the great sources of human angst?

T: “If you want to keep a secret, you must also hide it from yourself.” — Orwell. Since each project creates its own particular ethical fences, the borders crossed or left sacred and taboo, how does an author know if her art justifies the human risk?

E: Isn’t the important thing to measure secrecy against a matrix of pain and justice?

T: Maybe Lucky, soon to face the hordes, could measure the project’s revolutionary possibility, asking: what imagined reader have I summoned and helped by disclosing x or y? As if there might be an ethical offset tax!

E: Right: the example of honesty is often a source of a work’s lasting value. And those whose reactions are most feared are sometimes most forgiving. But to get practical: is there anything Lucky can do to manage others’ reactions? Is that the writer’s responsibility?

T: The vastness of any writing comes from the myriad of interpretations readers find in a given work. Here’s reader-response theory gone biblical: once you finish a work, you set your baby off in its cradle of river-reed bulrushes for the pharaoh’s daughter to find. Much as you might prefer otherwise, you cannot control a work’s reception — even if you are president-elect and your work happens to be a sub-par restaurant! Alongside the concept of killing your darlings — surrender the baby. Many beginning writers have the belief that, nonetheless, they must work overtime to control how readers accept a work. Even if every writer uses some imagined community as a magnet for his or her own aesthetic, a particular discourse. or readership, outcomes like to play tricks. Yet if Lucky’s work stays authentic to its ambition, its cradle will end up in the right bulrushes. Maybe! At least that’s the hope, or is it not?

E: What you describe is what all art is: a radical act of faith. And faith always involves risk. But perhaps that’s why we invented art: to give ourselves something so beautiful that it not only inspires faith — but sustains it.

T: Though anyone who aims to have radical faith knows it entails intermittent digging of the self up from its roots.

E: And trusting that the internal rewards are worth the interpersonal risks.

T: The bravest writers I know, the ones I most admire, sustain the exact negative capability evident in Lucky’s letter: writers aware of the cost, neither heedless narcissists nor writerly sociopaths but rather considering humanity in their work and life. Or, as Audre Lorde says: “I have come to believe over and over again that what is most important to me must be spoken, made verbal and shared.” So rest assured, Lucky: already you understand community, written and lived: all that makes up a writing life without lies, so essential in our moment.

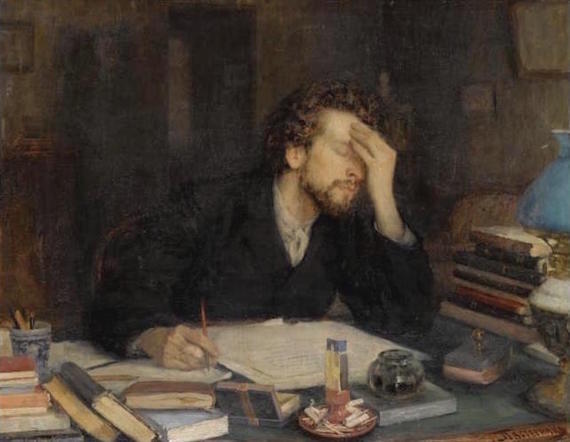

Image Credit: Wikipedia.