1.

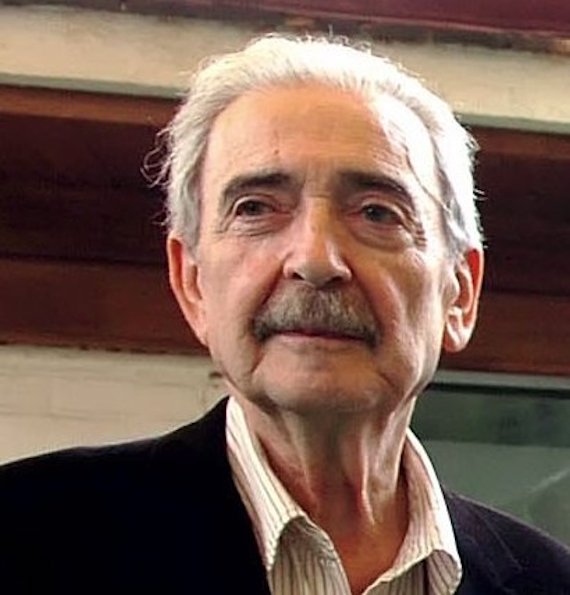

In April 2004, I found myself crossing Mexico City in one of those ubiquitous green beetle taxis with the front seat removed, on my way to interview an Argentine poet. The poet’s name was Juan Gelman. He was 72 years old and a giant in the world of Spanish letters, but it wasn’t literature primarily that I wanted to talk to him about. Rather, it was biography: the story of his life.

A month or so earlier, I’d come across an article in a French newspaper that described Gelman’s two-decade search for his missing grandchild. Amid the repression unleashed by the Argentine military coup in 1976, Gelman’s son and pregnant daughter-in-law had been abducted by one of the junta’s hit squads, the baby born in some dark torture center and appropriated, as were some 500 infants, by friends of the regime.

There was something in the constancy of Gelman’s quest that I found compelling — begun as it was with so little, nothing to tell him even whether the child was a boy or a girl. Surrounding this story were events that had seared his life with the sort of tragedy that nobody would ever want to face.

As the taxi approached Gelman’s street in the leafy neighborhood of la Condesa, I realized with some amazement that his apartment was practically back-to-back with the building where I had lived myself just a few years before. I had a powerful sense of parallel lives, which would remain with me long afterwards, and would come to infuse the novel that, at that time, I never imagined I would write. I remember most particularly that it was Easter, and that like every Easter in Mexico City, all the jacarandas were in bloom.

Gelman welcomed me into his study, which was hung with black-and-white photographs of his disappeared son and daughter-in-law and paintings by artist friends. He sat at his desk and I sat in a low armchair, and he began to tell me about his life, which seemed to span the great events of the 20th century.

2.

As a poet, Gelman is not widely known in the English-speaking world. But his stature in the world of literature in Spanish is enormous; the author of more than 20 books of poetry, he is famous not just for his writings but for his struggles in the field of human rights. He has won just about every major literary award in Spanish (including the Juan Rulfo, the Pablo Neruda, the Reina Sofía) and is the recipient, along with Jorge Luis Borges, Mario Vargas Llosa, Octavio Paz, and Carlos Fuentes, of the Cervantes Prize, the highest award in Spanish letters.

Gelman told me how his family, Ukrainian Jews, came to Argentina after his father escaped the Tsarist cavalry in the 1905 Russian revolution. Born in 1930 in Argentina, Gelman’s first encounter with poetry was at the age of five or six, when he’d listen to his elder brother reciting Alexander Pushkin in Russian. His first verses were love poems to local girls in Villa Crespo, a barrio of Buenos Aires; later, Gelman became a journalist and activist, doing propaganda work with the Monteneros, a leftist urban guerrilla group from which he later publicly broke.

But it was the events surrounding the 1976 generals’ coup in Argentina that changed him, and his poetry, forever. Threatened by the right-wing Triple A death squad for his involvement with the Montoneros, Gelman had already fled into exile in Italy when his son Marcelo, a 20-year-old journalist, and his 19-year-old daughter-in-law María Claudia were “disappeared.” They were among an estimated 30,000 people who were to vanish into the junta’s clandestine torture centers, many of them dropped to their deaths from planes. María Claudia was seven months pregnant at the time.

Though condemned by the Montoneros as a “traitor,” Gelman was wanted by the Argentine government for his former connections with them; a warrant for his arrest was dropped in 1988 after a successful petition led by the Nobel laureates Gabriel García Márquez and Vargas Llosa.

Swathes of Gelman’s poetry — often broken with slashes, and complex because of the plasticity of his language — come at the subject of grief elliptically, as if trying to grasp the meaning of loss: of his son, his country, his compañeros. His work is often a struggle for memory, and is often suffused with sadness, as in this extract from “Another Tango:”

we’ll make a morning lofty as a window/

our friends will come to look/

they’ll see the unborn skies

where stars were hung for lives more beautiful than this/

A creator of words, a maker of meanings, he once told an interviewer: “I write poetry because I have no other remedy.’’

3.

As the light faded, Gelman switched on his desk lamp, then opened his wooden filing cabinets, pulling old, typewritten police reports from his files. They detailed the accidental discovery of Marcelo’s body in a barrel of cement, and his subsequent inhumation in an anonymous grave. In his heavy Argentine accent, Gelman recounted events that, although terrible to hear, must have been many times harder to live. He told of how Argentine forensic anthropologists had finally managed to identify Marcelo, allowing him and his first wife to at last lay their son to rest.

When Gelman saw how his retelling was affecting me, he said there was no need for sadness. “This is a story with a happy ending,” he said.

And in one way it was, because he had found his granddaughter. After years of false starts, of petitioning national and supranational governments, of publishing open letters in the newspapers of Latin America, Gelman had pieced together the shreds of evidence and had tracked her down — in Uruguay, where María Claudia had been taken as a prisoner and had given birth, her baby handed over to a police family to raise as their own.

Mindful of the psychic shock that being confronted with the truth could provoke in someone unaware of her true history, Gelman asked a priest to act as an intermediary. A meeting was arranged, and at last the poet stood face-to-face with his granddaughter.

Because their encounter was still relatively recent, and because Gelman was careful to protect his granddaughter’s privacy while she came to terms with her new identity, he declined to say much about her, a silence that the media, too, had so far managed to respect.

Gelman was right: his story did have a happy ending. But in another way it did not. He had lost his son; what had happened to María Claudia remained unknown. Gelman was still searching for her when I met him; she remains missing to this day.

4.

In 2014, a decade after that conversation with Gelman, I was nearing completion of the novel the seed of which had been planted during that long afternoon in his study, when word came from Mexico City that the poet had died. Tributes poured in from around the world; Argentina declared a day of national mourning; in Barcelona, the consulates of three countries opened condolence books for citizens to sign.

In Paris, a group of Argentine exiles I had met through my research invited me to a commemoration of his life. Poems by Gelman were read, a documentary of his life was shown, and musicians played the tangos he so loved.

Then, a young woman of great poise came to the microphone. Though many years had been stolen from them, Macarena Gelman, the granddaughter Gelman had told me about without disclosing her identity, spoke of her relationship with her grandfather, of her first meeting with him even before they received the genetic proof that they were related, and what it was like to discover his history that had now become hers.

“There was enormous empathy,” she said of their first encounter. “We didn’t know each other, we still had a whole path to travel to be certain I was his granddaughter,” she said. “It was very delicate, and very lovely…There was a great deal of respect.”

Now a young deputy in the Uruguayan parliament, Macarena and her grandfather fought side-by-side for word of what had happened to María Claudia, whose own mother became a founding member of Argentina’s Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo. The police officer who appropriated Macarena has died, but she maintains her relationship with the family she grew up in, while being welcomed into the one she had lost.

While identity may take a lifetime to come to terms with, she told me, “the links can become more healthy, in spite of what took place.”

5.

Gelman’s life continues to travel with me. I am writing this essay in a courtyard of the university of Alcalá de Henares, the birthplace of Miguel de Cervantes, where I am a writer-in-residence just outside Madrid. It is here, each year, that Spain presents the Cervantes prize; here, eight years ago, that Gelman walked through this same courtyard to receive the award from the Spanish king.

His name has its place of honor here on the wall of the 16th-century Paraninfo, one of the architectural treasures of Spain, and it seems fitting that his courage, the generosity of his spirit, and the inspiration of his poetry should find their echo in the beauty of this place.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons.