1.

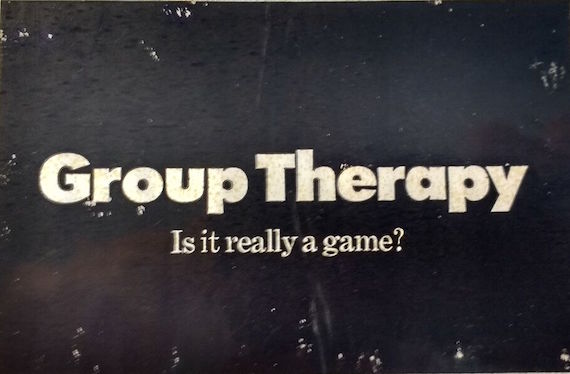

Before A Question of Scruples, Loaded Questions, or Curses; decades before Cards Against Humanity, Drunk Stoned or Stupid, or Never Have I Ever; before Nasty Things, What’s Yours Like?, or Disturbed Friends, there was Group Therapy, the original psychological adult board game. Released in 1969, Group Therapy straddled the free-love ’60s and the ’70s Me Decade, groovy and real, a plain black box with white text, just the name and question: “Is it really a game?” Yes, reads the instruction booklet, Group Therapy is a game. “But Group Therapy is for people who want to do more than just play games. For people who want to open up. Get in touch. Let go. Be free.”

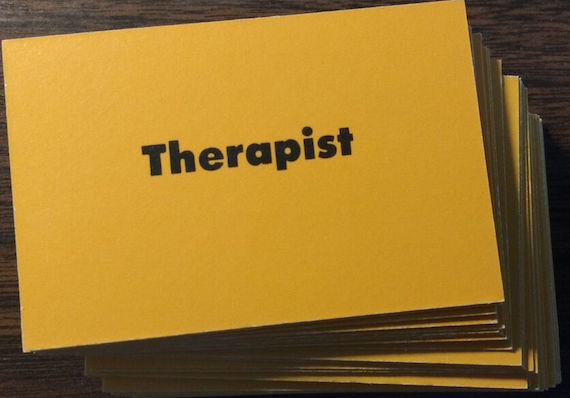

The rules are simple. Players move their tokens along a game board from the beginning space marked “Hung Up” to the final space marked “Free.” To reach “Free,” players must draw from three decks of cards and perform the cards’ instructions. These tasks grow more difficult as you move along the board, from yellow to blue to red.

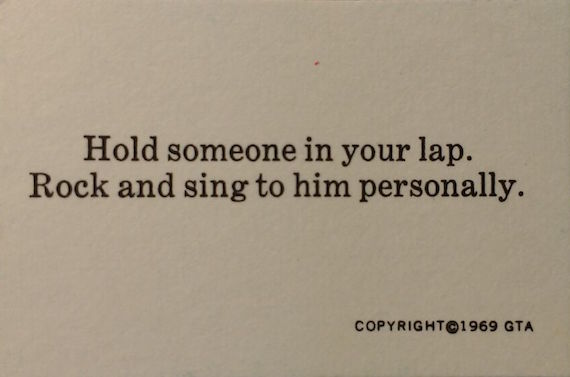

From the yellow deck: “Ask someone to hold you and rock you. Give yourself to the experience.”

From the blue deck: “Stand facing the group member who threatens you most. Pushing your hands against his, tell him why he frightens you.”

And from the red deck, my absolute favorite card: “You have been accused of over-intellectualizing your hang-ups. Respond — without falling victim to that criticism.”

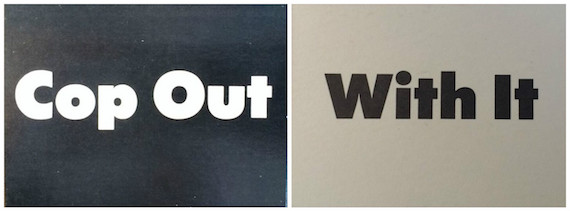

Within a minute after performing each card’s instruction, players must issue a judgment by displaying a card. One side reads “With It,” the other “Cop Out.” With each “With It” judgment, players advance a space, and go back for each “Cop Out.” A player may also read, pass, and move their token one space back.

A better tagline for Group Therapy might be one I read online: “It’s like Candyland except with more awkwardness and crying.”

2.

By 1969, group therapy had entered the mainstream. Name any hang-up or cause, and chances are there was a seminar or encounter group growth center tasked with working it out: Gestalt, nudist, psychodrama, Jungian, feminist, peak experience. Group therapy members pounded pillows, stared, screamed, danced, touched each other’s faces, or simply talked. It made sense that the non-analysand majority would want to take part, and board game makers were happy to oblige. By 1970, therapy-themed adult games integrated front-page concerns such as pollution (Smog, Dirty Water), race relations (Black and White), and politics (V.I.P. Theater). It was the Group Therapy game that sold the most copies and garnered the most news coverage.

“A lot of bizarre things are going on in American living rooms these days,” a Newsweek story begins. “Young men and women are shedding their clothes, shadow boxing, shouting out their deepest fears, or cradling each other in their arms.” One husband “failed to move out of ‘hung up’ all evening, went home and shouted at his wife for hours, spewing out pent-up venom and self-pity.”

To play Group Therapy, Sandra Blakeslee writes in The New York Times, “a person has to be willing in some degree to expose his psyche, relax his defenses and admit his anxieties, frustrations and loneliness. No one needs to become more vulnerable than he wishes, but many find the honest of the experience enlightening.”

3.

Saturday, November 3, 1973. All in the Family, the number one show in the country with an average weekly audience of 20 million viewers, airs an episode entitled “The Games Bunkers Play.” Mike, better known as “Meathead,” breaks out a board game after dinner and invites his friend, Lionel Jefferson, and the Lorenzos, the Bunkers’ neighbors, along with Archie, Edith, and Gloria to play.

“It’s a psychological game — if you play this game right, you could really learn a lot about yourself,” Meathead explains enthusiastically. “You pick a card when it comes your turn, you read it and do what it’s says.”

“Sounds left-wing to me,” Archie quips.

Archie picks the first card: “Do an interpretive dance that shows how you feel when you think nobody likes you.” The audience erupts in laughter. Archie makes a face, picks another: “Discuss the part of your body which you are most proud of.”

With that Archie exits (“I’m doing my interpretative of a guy going down to Kelsey’s for a couple of beers.”) The group plays on. Meathead loses his cool when they judge him as a “Cop Out.” He accuses everyone of criticizing him just as harshly as Archie. Edith follows him into the kitchen. Archie doesn’t hate you, Edith explains. He criticizes you because he sees in you all the things that he can never be.

When Archie comes home, oblivious to what had gone one, Mike says he understands and hugs him.

4.

Inside our home in Maple Shade, N.J., a working class suburb of Philadelphia, the Summer of Love arrived around 1975. Mom, who worked part-time as a secretary at our Catholic school, read Leo Buscaglia pop psychology books and prayer booklets she kept in her bedside table. Dad, a local delivery truck driver, played whale call cassettes and ordered home wine-making kits. We traced biorhythm charts with a Spirograph-looking instrument that determined if our energies were compatible, if we were having “up” or “down” days. Mom and Dad may have taken part in a few hippie things, but were far from hippies. They had more in common with All in the Family than Jefferson Airplane.

Dad bought Group Therapy at a toy store in 1974. Mom’s high school friends, ex-cheerleaders all, came by to play, and brought their husbands along. Marlboro smoke filled the kitchen on these adult get-togethers. I am reminded of one night when I was eight years old, sitting down next to empty bottles of Boone’s Farm wine, and insisting on playing the game as well.

I drew the card that read “You are advertising yourself as a lover. What does the ad say?”

Mom told me to pick another one, then sent me back to bed, without the group giving their judgment

5.

At the bottom of each Therapist card reads a line in the same Times Roman typeface as the game’s text: “copyright©1969 gta.” The game’s instructions spell GTA out as “Group Therapy Associates.” A line on the direction’s last page reads “Group Therapy was prepared with the assistance of Joseph Schlichter, psychotherapist, New York City.” Online searches for Schlichter lead to dead ends, except for a few articles that mention Trisha Brown, Schlichter’s ex-wife, a modern dance pioneer and company founder. Schlichter appeared in the daredevil performance of her 1970 work “Man Walking Down the Side of a Building” by descending their building on 80 Wooster in a harness. I come across a listing for a Joseph R. Schlichter, 83, with an address in Hawaii. I leave a message on a phone number. No one calls back.

6.

I come across a 1999 letter to The New York Times from Daniel M. Klein of Great Barrington, Mass. “As one of the creators of the 1960s board game Group Therapy,” Klein begins, “I must protest Lucinda Rosenfeld calling it ‘utterly unironic’ in her review of Paul Solotaroff’s new book Group. After all, the game’s subtitle was ‘Is It Really a Game?’

“I had to say that. I feel better now. Anybody else?”

I find Klein on Facebook and write him a message. In his email response, he copies his two co-authors, Phil Ross and Susan Perkis Haven.

7.

It’s nine o’clock. My wife and I have been playing for about 30 minutes. Each of us have issued two Cop Outs and two With Its. It looks like it’s going to be a tie. The next card I pick — the one that reads “Contract all the muscles in your body from scalp to toes. Hold this for at least 30 seconds” — leaves me red-faced and out of breath. I get a With It. My wife’s next card also calls for something physical — “Move in a way which is uncharacteristic for you, but normal for other people” — and prompts her to move in an exaggerated strut, reminiscent of the “That’s right, we bad” walk Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder do in the prison comedy Stir Crazy.

I laugh and throw up a With It, for the effort alone.

It occurs to me that we are more comfortable with the movement-oriented Therapist cards than ones that require us to talk. When I am asked to “Stand up and tell the group what makes you mature,” I find it difficult to come up with a convincing answer, other than to say that I had a job and was married with children.

Maybe the game really works?

8.

Spring 1968. Three new friends meet for dinner at the Upper West Side apartment of journalist Phil Ross, which he shares his wife and baby daughter. One guest, Daniel Klein, a recent Harvard graduate who majored in philosophy and former joke writer for Flip Wilson, brings up the phenomenon of encounter groups and group therapy. He had just returned after some time abroad, and marveled at all the meeting groups popping up in the city. “It all sounds like a game to me,” he says.

“Well, if you think about it,” another guest, Susan Perkis Haven, a freelance writer who had worked for Margaret Mead, suggests, “maybe it really is a game.”

They laugh. A lightbulb appears over their heads.

“We were enterprising young people,” Klein writes to me 48 years later.

9.

The trio meets at Haven’s apartment, also on the Upper West Side. They create a mock-up of a game — board, pieces, cards — and recruit friends to try the thing out. Through Ross’s father, a meeting is set up with executives at Park Plastics, based in Linden, N.J., then the biggest manufacturer of water pistols.

“I think they were bemused by us,” Ross tells me over the phone. “Here were these people who made water pistols all day, and we were these three young wiseass kids. I think we added a little freshness. They said, ‘we’ll give it a shot.’”

Work began in earnest by Spring 1968, when Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy were assassinated. “You have to remember the game was a product of its times,” Ross says. “We were all moderately caught up, as was anyone else, in the times, which really were a-changing. Everything was being turned upside down.” By the summer of 1969, the trio shared a cabin in the Berkshires, putting on the final touches, watching the moon landing. “We didn’t necessarily see ourselves as part of all that was going on,” Ross tells me. “But ultimately I think it was. This is not an idea I think I could have had or had an audience five, six years before. Or 10, 15 years after.”

10.

Park Plastics could sell and distribute the game, and could make the plastic half-moon game pieces, but Ross and his co-creators were on their own when it came to making everything else. “We had to go out and find a box-maker, a board-maker, somebody to wrap the playing board onto,” Ross says. The game’s secret ingredient rests in its design. Peter Rauch and Herb Levitt, who worked with top-notch design firms Pentagram and Push Pin, opted for a simple, streamlined design, with bright colors and serif typefaces on the board and cards and plain packaging on the outside. The Park Plastics folks balked at first.

“People said that’s crazy — it needs to be colorful,” Ross says. “Whoever heard of a game that was in a black and white box?”

11.

The package arrives on my doorstep, my name and address written neatly in black marker, wrapped tightly with tape, each item boxed inside another, like Russian nesting dolls, surrounded by balled-up newspaper. My most recent eBay purchase, a mint-condition copy of Group Therapy, replaces the set I grew up with, the one I brought out in college to show off at parties, abused with beer and bong water stains, and then lost entirely.

One stack of Therapy cards ended up in the hands of an aspiring rapper named Pussy Galore, who ended up in my apartment in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. We met in the elevator of a building in midtown Manhattan, where I was temping for a record label. The R&B trio Sisters with Voices had just visited that day. As I left, Pussy Galore hopped on the elevator, escorted by security. She followed me home, drank beer, and I showed her the game box. She started flipping through the cards, reading them out loud and laughing. Later, she popped her rap demo into my cassette deck, and proceeded to perform a dance routine on my small living room floor.

The remainder of the game ended up in a needle exchange on the Lower East Side where, over a series of Saturday afternoons in the late-1990s, I led creative expression classes. Clients who used intravenous drugs spent time at the exchange to get condoms and clean needles and take part in harm reduction programs — anything from reiki massage, acupuncture, glamor make-overs, or writing poems on a couch with a graduate student. I brought the game along to show to a counselor. I never saw it again.

12.

March 2016. My car’s GPS tells me to pull over in the middle of a neighborhood in Linden, N.J. I look at a one-story building. Its windows are boarded up and the stucco exterior flaking away, but I know I’m at the right place when I read the sign: “Park Plastic Molding.” I peek inside a window: piles of paper cover the floor around two desks. On one I see a can of spray paint.

This building once housed the world’s largest manufacturer of water pistols.

For much of the 1960s and ’70s, Park Plastics cranked out water-propelled rockets, woodpecker bubble blowers, miniature ping pong sets, blow guns, flying saucer pistols. A good portion of Park Plastic’s guns were fashioned to resemble life-like Mausers, submachine rifles straight out of mafia capers, Western-style six-shooters with holsters. Many items were sold in the aisles of my childhood 5 & 10. I look at those toys now and picture a child brandishing one in a park at nightfall, a frightened neighbor, a trigger-happy policeman.

13.

I ask Ross if he had any favorite Therapist cards. He does not. He hasn’t seen a copy of the game in years. One card sticks out in his mind, he says. It’s one that Klein wrote.

“I am trying to remember,” he says. “Danny majored in philosophy at Harvard. It was a meta-question, really.”

I think I know, I say. “Was it the one about being accused of over-intellectualizing hang-ups and to respond without falling victim to that criticism?”

“Yes!” Ross says. “I remember saying, ‘Come on, Danny.’ But he insisted.”

14.

The All In The Family episode gives story credit to Susan Perkis Haven and Dan Klein, but that wasn’t always the plan. Haven remembers they had pitched another idea for an episode. “The script was about family conflict and generations and time moving on and generational jealousy and lots of less than hysterical things!” Haven tells me. The staff at All in the Family rewrote it and made it about the actual game.

The new script, written by Michael Ross and Bernie West, was “much funnier probably,” Haven says. “We were both pleased by the publicity about the game and miffed that our script was changed.”

Klein declines to address the episode of writing, or not writing, the episode (“I think I’ll pass on this one”), other than to say that he “didn’t think the TV episode increased sales significantly.” But many did capitalize on the game’s link with Archie Bunker. “We Have It…The Game Rage of the Age” reads an ad in Louisville, Kentucky’s Courier-Journal. “As seen on ‘All in The Family,’ Saturday, Nov. 3.”

15.

Group Therapy spawned a sequel (Couples, more on that soon), parodies (Therapy!) and imitators (Un-Game, Sensitivity, Compatibility, Ego), but it was Group Therapy that sold half a million copies (by one conservative estimate), was discussed on The Tonight Show, and advertised in newspapers from Arizona to Florida.

“Group Therapy was the first game of its kind,” Ross tells me over the phone. “There was no other game where how you did in the game was not a function of either luck or skill, but of how other players judged you. That was unique.”

It does sound a lot like how we react to Facebook posts, click hearts or retweet, up- or down-vote, swipe left or right. With it or copping out, all judged in our worldwide group therapy game on the Internet. Whoever advances merely has to act authentic, or at least convince a majority of being With It, to be truly free.

It’s difficult, even impossible, for me to recall a time when we weren’t always judged this way.

16.

Group Therapy “took care of us for a couple years” financially, Ross says. “We weren’t living luxurious lives, but we realized that with the success of Group Therapy that we could become our own little game company.” They put out a sequel, Couples, one that uses a similar concept, this time with triangle-shaped cards and equally audacious scenarios (Sample card: “Woman: you are a photo-editor assigned to get this man to post nude for a centerfold. Man: React the way you really would.”) A third game, Battle of The Sexes, was also in the works.

Then things changed. “Halfway through Couples, I think we collectively realized that we did not want to spend our lives making games,” Ross says. “The air kind of came out of our balloon. And so we never made attempts to publish more. We all went our separate ways.” They did continue to collaborate. Haven and Klein wrote Seven Perfect Marriages that Failed. Ross and Haven were paid to write several sitcom pilots, as well as punching up scripts. Ross and Klein wrote a screenplay, optioned by ultimately unproduced, called The Middle Age Champion of the World.

“It was about a guy in his 40s, an Upper West Side, liberal kind of guy, who was working at a PR firm and he felt had no meaning in his life, he’s married and has a couple of kids, and he decides he wants to have a professional wrestling match,” Ross says. “His wife, his friends, and his therapists, all think this is a horrible idea, that he’s gone off his rocker. But he wants to have one pure moment. He wants to experience something clear and unadulterated, that isn’t bullshit.”

Klein continued to write and has in his 60s found a niche as a best-selling co-writer of philosophy-themed humor books, beginning with Plato and a Platypus Walk Into a Bar: Understanding Philosophy Through Jokes. Forty years after Group Therapy, Ross and Haven both work as therapists, each with their own practice, he in the Adirondacks in Upstate New York, she on the Upper West Side.

Klein continued to write and has in his 60s found a niche as a best-selling co-writer of philosophy-themed humor books, beginning with Plato and a Platypus Walk Into a Bar: Understanding Philosophy Through Jokes. Forty years after Group Therapy, Ross and Haven both work as therapists, each with their own practice, he in the Adirondacks in Upstate New York, she on the Upper West Side.

“It is weird that Phil and I both became therapists,” Haven says, “but I think it had more to do with our being writers and interested in people and behavior and just being introspective. When we were freelancers, we did so many things to pay the bills. But once you have kids, you want something fulfilling but also steady. And this just fit me. I love doing it, probably even more than writing.”

No one mentions in their biographies the game they wrote that made its way into half a million homes.

17.

In “The Search for Marvin Gardens,” John McPhee tells us how “a group from Racine, Wisconsin” played Monopoly for 768 hours straight, and how he and a friend have played thousands of times. Monopoly “reached to the profundity of the financial community” in its exact reflection of the business milieu at large.” Reading this, I realized, quite suddenly, that Group Therapy, my game, was beside the point. Group Therapy represented a time when my family was still together, played games together. When we opened up. Got in touch. Let go. Were free. Did I ever, lugging that box from apartment to apartment, play a real game of Group Therapy? No. The game is beside the point. I find myself replacing things from my childhood, item by item, in the hope the child returns.

18.

Card after card, my wife and I move around the board’s circle, yellow to red to blue spots, from “Hung Up” to “Free.”

I pick up a card. “Tell the group what effect fame would have/has had on you,” it says.

I stare at “would have/has had” part, and try to define fame. What level of fame are we talking about? My wife gives me a look that says get on with it. And so I tell this story that I have told her many times before, about the effect a Major National Newspaper’s negative review of a book I wrote had on me. I tell her the short version.

It was the second time the Major National Newspaper panned one of my books, actually, but this time it was worse. Much worse. I considered my life ruined, done, or at least the writing part of it. I called the effect of the bad review a crack-up, since that’s the term F. Scott Fitzgerald uses. A more accurate term might be nervous breakdown. I stayed in bed for weeks except to go to work or go the bathroom. Mornings, our oldest daughter climbed over the bedspread to look for me under the pillows. Days and days of woe-is-me dread, crying, resignation, then moments of rage and looking up the fucking reviewer’s address.

I finish talking.

My wife must again issue her judgment regarding whether or not, as the game’s directions state, I “adequately fulfilled what was asked” of the card. Her face expresses genuine empathy.

She holds up her card: “With It.”

We smile. I pick up my plastic piece and advance one space.

We continue to play, not as a group, but as a duet. We will learn a little more about each other. Neither of us will win.

Images courtesy of the author.