1. Reprise

This was the year I lived in a log cabin in the redwoods and then — suddenly, crudely — I didn’t.

This year I moved back to San Francisco after moving away just a year earlier, just for a minute, a break, just for some air, and when I returned I found I didn’t love you anymore, SF.

This was the year I found wrinkles around my mouth and eyes, the year of three more tattoos because fuck it, I mean we’re all going to die/become climate chaos refugees anyway, I mean did you notice how crazy the weather was this year?

2015: It was the year of cooking more. Of jazz. It was the year of bupropion, the year of boot camps, the year I sold my first nonfiction book and didn’t finish my first novel. The year my friends all bought houses and I didn’t. A year of trying to be more like an adult, and a year of understanding how I never will be.

In the cabin, books felt realer. The woodstove replaced the TV. I started doing things like baking cookies and hanging bird feeders and sleeping all night. My partner and I stopped going out much, and when we did it was always to a dive bar and always for hamburgers. But we were lonely. We missed our friends. And so I read with friendship in mind, searching for female companionship in a way that I haven’t since junior high school. Most of the novels I read and loved this year were also books I was revisiting. I loved these books because they are at heart about women, about “little” lives, and about what it means to become oneself.

2. #squad

I re-read Colette’s Claudine at School; Colette was a self-mythologizer of Greek proportions, and all us lady writers today could learn a thing or two from her swagger.

I re-read Colette’s Claudine at School; Colette was a self-mythologizer of Greek proportions, and all us lady writers today could learn a thing or two from her swagger.

I binge-read every E.M. Forster novel, and realized how key turns in each book hinge on women; characters who may be small in deed or acknowledgment but whose impact looms large. (In my head, I call them Forster’s Girls, as though they’re some sort of Pink Lady-like posse, which is probably a terrible thing to think?) Cousin Charlotte in A Room with a View; idealist Helen Schlagel in Howards End; terrified, terrible Adele Quested in A Passage to India. These women fuck shit up, for good or bad, in part because they cannot help but yield to their true selves.

For the first time, I read Department of Speculation (Jenny Offill) and The Folded Clock (Heidi Julavits) and Everything I Never Told You (Celeste Ng) — books with small interiors but tremendous landscapes, each about women struggling in some way with what I’ll call, for lack of a better word, domestication.

For the first time, I read Department of Speculation (Jenny Offill) and The Folded Clock (Heidi Julavits) and Everything I Never Told You (Celeste Ng) — books with small interiors but tremendous landscapes, each about women struggling in some way with what I’ll call, for lack of a better word, domestication.

On the wilder side of the spectrum, I read Get In Trouble over and over again and I still have no idea how the fuck Kelly Link does it.

I got to know some new heroes a bit better in sequels — Sarah McCarry’s About a Girl and Katie Coyle’s Vivian Apple Needs a Miracle — and I felt grateful for women younger than I being stronger than I am. Then I invited over The Girls from Corona del Mar (Rufi Thorpe) and the Collected Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay, girls who maybe aren’t heroes but maybe I like them better that way.

I got to know some new heroes a bit better in sequels — Sarah McCarry’s About a Girl and Katie Coyle’s Vivian Apple Needs a Miracle — and I felt grateful for women younger than I being stronger than I am. Then I invited over The Girls from Corona del Mar (Rufi Thorpe) and the Collected Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay, girls who maybe aren’t heroes but maybe I like them better that way.

Finally, I read Elizabeth McCracken’s Thunderstruck, and I remembered how the best stories are edged with grief.

3. Ablutions

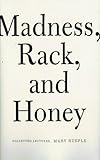

In Madness, Rack, and Honey, Mary Ruefle writes in defense of sentimentality: “Nostalgia, which evokes sentimentality, belongs exclusively to culture. Because it belongs to the idea of progress and change and the idea of accumulation, accretion and storage.”

In Madness, Rack, and Honey, Mary Ruefle writes in defense of sentimentality: “Nostalgia, which evokes sentimentality, belongs exclusively to culture. Because it belongs to the idea of progress and change and the idea of accumulation, accretion and storage.”

When I moved back to San Francisco this year, I did so for the fifth time in two decades. This time, though, there is a new sentimentality attached to my interactions with the city. It’s neither pure regret nor Vaseline-lensed nostalgia; more like a backwards-facing gaze, a constant awareness of what Ruefle might call the city’s “accumulation.” When I walk around this town, I can’t see it clearly, I’m so clouded with visions of lives I have lived here, things I did or didn’t do, and — most urgently — what isn’t here anymore. When I look at San Francisco now, my eye’s camera loops a constant montage of how it used to be. Jobs and apartments, lovers and friendships and grocery stores, the behavior of the clouds. How we used to be, it and me inside it. Every intersection stores a memory, and every time I cross one I have the surprising feeling that I don’t belong to this place anymore. It’s surprising mainly because I hadn’t realized I felt like I belonged.

Along with my nostalgia, I’ve been regressing into analog entertainments, to coloring books and piano lessons and young adult classics I haven’t enjoyed since girlhood. These diversions comfort me because they still feel like me. Undisrupted me. Who I was in all the thens and who I am now are not the same, as my city is not the same, but we are still ourselves.

I’m told this is a pretty typical sensation for a person to have in her 40th year of life. I’m told San Francisco is changing, has changed, will always be a city of change, so get over it. I’m in the midst of reading Ada Calhoun’s St. Mark’s Is Dead: The Many Lives of America’s Hippest Street and so I’m thinking about how yes, cities change. Culture proceeds. Sentiments accumulate. However, not all change is good change. That there are cycles of boom and bust on a particular parcel of land doesn’t render irrelevant the wrongs done in service of those cycles. The disappearance of my San Francisco is a big deal, to me.

I’m told this is a pretty typical sensation for a person to have in her 40th year of life. I’m told San Francisco is changing, has changed, will always be a city of change, so get over it. I’m in the midst of reading Ada Calhoun’s St. Mark’s Is Dead: The Many Lives of America’s Hippest Street and so I’m thinking about how yes, cities change. Culture proceeds. Sentiments accumulate. However, not all change is good change. That there are cycles of boom and bust on a particular parcel of land doesn’t render irrelevant the wrongs done in service of those cycles. The disappearance of my San Francisco is a big deal, to me.

4. Those Who Leave

Like everyone else, I mainlined Elena Ferrante this year, reading all four books in her epic and important Neapolitan series. After I finished The Story of the Lost Child, I was at a loss. What could I possibly read next, what act could follow Ferrante’s? I loved her so much, so unironically. I wanted to stay close to her characters, Elena and Lina. I had an inspiration: I would re-read Little Women, the novel that, in My Brilliant Friend, inspires the girls to become readers and writers, to push beyond the usual boundaries of their neighborhood and their gender.

Like everyone else, I mainlined Elena Ferrante this year, reading all four books in her epic and important Neapolitan series. After I finished The Story of the Lost Child, I was at a loss. What could I possibly read next, what act could follow Ferrante’s? I loved her so much, so unironically. I wanted to stay close to her characters, Elena and Lina. I had an inspiration: I would re-read Little Women, the novel that, in My Brilliant Friend, inspires the girls to become readers and writers, to push beyond the usual boundaries of their neighborhood and their gender.

Louisa May Alcott’s children’s classic was published in two volumes in 1868 and 1869; it follows the four daughters of the March family, each of whom embodies a neat archetype. The Marches are poor, or at least Gentlewomen In Classic Literature Poor — the girls all have jobs as teenagers, but the family still has a maid. And they are literate and progressive and loving; they do all right for themselves.

I read Little Women obsessively as a girl. I even had the book-on-tape (an actual cassette). This time around, it was a bit harder for me to roll with all the moralism. Each escapade of each sister always ends in a tidy lesson, usually summarized by their wise, perfect Marmee and immediately grokked by all the girls. Despite such antiquated conventions, Alcott’s writing shines through. Little Women is a YA page-turner, each short chapter leading addictively to the next, tears and all. Ferrante and Alcott have that in common, as well as the driving principle behind their work: I can sense in both these authors’ bracing rhapsodies an assertion of value, a celebration of the delicate plainness of la vie quotidien.

I was a Jo, I was always a Jo. Most American girls were, I think (and “most” includes Louisa May Alcott herself). Jo March is rebellious and defiant of gender norms, passionate and tortured in her writing; she is smarter and more useful than the people she loves, but still devoted to them. Mostly, she incapable of being anyone but herself.

But upon this re-read, the first in probably 25 years, it’s Amy March who is a revelation to me. Amy is the baby, the blonde, the sibling antagonist to Jo’s heroine. Amy is not as good and pure as pitiful, one-note Beth, nor as docile as Meg. She wants to be an artist, a genius artist, although she would also settle for having enough money to devote herself to just working really hard at her art, genius or no. When I was a girl, Amy struck me as a snob, shallow and insipid. Her destruction of Jo’s book manuscript (spoilers!) seemed unforgiveable — oddly, far more so than a similar act in Ferrante’s epic.

Now, however, Amy’s character has stretched and grown with age. There is something about a woman who, deep inside the drab gray of Civil War-era New England, desires elegance and then goes out and acquires it. Not the false elegance of fancy clothes and leisurely French carriage rides (although Amy gets those, too) but the elegance of good character. Throughout the book, Amy is trying to be — to become — a better person. She fails a lot and gets lucky a lot, but at least she tries. At the end, Amy gets the boy — the boy who as a girl I furiously wanted for Jo. But Amy gets the boy only because she demands the boy be worthy of her, something none of her sisters ever bothered to do.

Unlike her sisters, Amy has experience with and exists within the larger world as well as within her family. As she wishes and wills and learns and, yes, works herself into intelligence and grace, Amy stands increasingly apart from her family. She is the only character in Little Women who actually evolves.

I wonder if Elena Greco, Ferrante’s main character/cipher, imagined herself to be Jo. She’s not; she’s Amy, the one at a slight remove from all the rest, the one who leaves the swaddle of family and habit for the bigger life she knows exists out there. Elena struggles to choose art over home. Like Amy, she is always strong-willed but never too brutally so (well, mostly never). If Elena is Ferrante’s Amy, then Lina must be her Jo. Like Jo, Lina stays even when she could go. She is hot-headed enough to destroy her own chances for transformation; as Jo did, Lina chooses her community over her own brilliance, her art. And, like Jo, she is impeccably, immovably, tragically herself. Elena wears masks, she code switches, she travels between two worlds and learns to speak fluently the languages of her different existences. But Lina, although she may be at times swayed by men or money or work or tragedy, is incapable of camouflage. She does not become; she is.

5. Volver

When you leave and then come back, you get new eyes. In San Francisco this time, I’ve uncovered a type of grief that I do not perhaps yet fully understand. A place becomes a home without you realizing it; when it stops being so, it’s sometimes equally difficult to know. Over the course of decades, people become themselves, without note. It’s only when we look back that we see the shape we’ve taken, see its shadows and imprints. In returning to the stories that have shaped us, we see too how we have been mis-formed, which parts of us have been cast in coppery truths and which have failed to adhere.

And so to the tidy moral: My reading list this year was about growing up, I guess; about how, be we little or epic, we become.

More from A Year in Reading 2015

Don’t miss: A Year in Reading 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010, 2009, 2008, 2007, 2006, 2005

The good stuff: The Millions’ Notable articles

The motherlode: The Millions’ Books and Reviews

Like what you see? Learn about 5 insanely easy ways to Support The Millions, and follow The Millions on Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr.