“Spring and Fall,” written by Gerard Manley Hopkins in September, 1880, and collected in his Poems and Prose, is the saddest poem ever written. I have been moved by other poems, including “Rock Me Mercy” by Yusef Komunyakaa, “Saying Goodbye to Very Young Children” by John Updike, and “Aubade Ending with the Death of a Mosquito” by Tarfia Faizullah. There are countless more poems, published and unpublished, seen and unseen, that could scar my heart. Yet in 15 lines and 94 words, Hopkins builds a melancholic, elegiac sentiment that still affects me now, hundreds of reads later.

“Spring and Fall,” written by Gerard Manley Hopkins in September, 1880, and collected in his Poems and Prose, is the saddest poem ever written. I have been moved by other poems, including “Rock Me Mercy” by Yusef Komunyakaa, “Saying Goodbye to Very Young Children” by John Updike, and “Aubade Ending with the Death of a Mosquito” by Tarfia Faizullah. There are countless more poems, published and unpublished, seen and unseen, that could scar my heart. Yet in 15 lines and 94 words, Hopkins builds a melancholic, elegiac sentiment that still affects me now, hundreds of reads later.

The poem is invoked to a “young child,” Margaret, who is the silent recipient of the adult narrator’s lament. Hopkins composed the poem while serving as a parish priest in Lydiate, England, and occasionally celebrated Mass at Rose Hill, a private home. He was not a successful preacher, and, devoid of a “working strength,” soon left pastoral work. He taught intermediate Latin and Greek for three years, and then became Chair of Classics at University College, Dublin. He found little joy in any of these professional endeavors, and died of typhoid fever on June 8, 1889. His poems were not published until 1918, by his friend, British poet laureate Robert Bridges.

Márgarét, áre you gríeving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

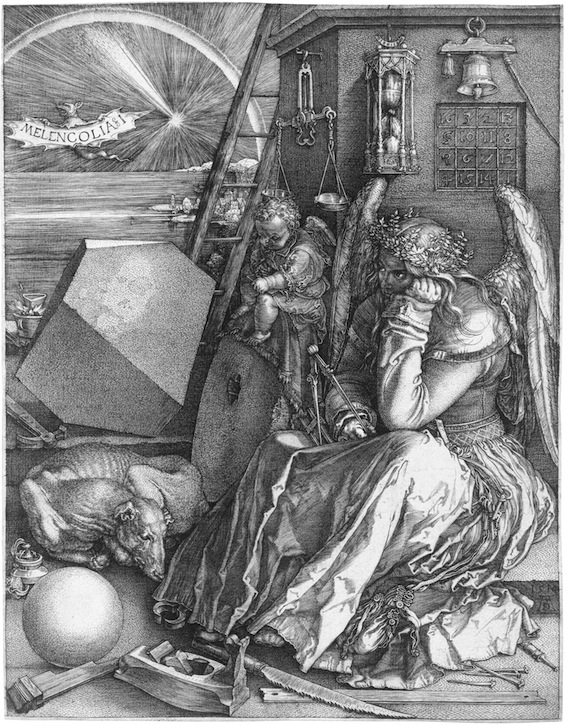

Hopkins was, by our imperfect hindsight, a depressed man who loved God. Much has been written about the tension between his artistic and ascetic selves, but even that paradox is romanticized. The Spiritual Exercises, the cornerstone of Hopkins’s Jesuit training, is not meant to neuter one’s personality, but rather to focus the mind. His poetic lines pulse with the passion of a believer, and they must be read through that lens. But he was also a profoundly melancholic man.

The concept of melancholy was essential to essayist Michel de Montaigne, whose works were poetic in their associations and rhythms. In Montaigne and Melancholy: The Wisdom of the Essays, M.A. Screech argues that this melancholy, then considered one of the four bodily humors (black bile), resulted in both sadness and rapturous ecstasy. The ecstasy of sex, but also the ecstasy of mystical experiences, much like the polarized moods within Hopkins’s poems. Montaigne might have been closer to the humor of Cicero (“Aristotle says that all geniuses are melancholic. That makes me less worried at being slow-witted.”) than the darkness of Hopkins, but they share a willingness to explore sadness.

The concept of melancholy was essential to essayist Michel de Montaigne, whose works were poetic in their associations and rhythms. In Montaigne and Melancholy: The Wisdom of the Essays, M.A. Screech argues that this melancholy, then considered one of the four bodily humors (black bile), resulted in both sadness and rapturous ecstasy. The ecstasy of sex, but also the ecstasy of mystical experiences, much like the polarized moods within Hopkins’s poems. Montaigne might have been closer to the humor of Cicero (“Aristotle says that all geniuses are melancholic. That makes me less worried at being slow-witted.”) than the darkness of Hopkins, but they share a willingness to explore sadness.

“Spring and Fall” is spoken to Margaret. Her name is mentioned in the first and final lines, folding the poem together. Hopkins, like other poets, often accomplishes that wrapping of word and idea through poetic form and rhyme, but the repetition of her name is a reminder that she is being offered advice. She is sad because the trees are losing leaves. We want to tell her to get over it, perhaps, so as to not waste her tears on such a trivial thing. But the narrator reserves his tough and honest love for the moment.

Leáves like the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

In the first four lines, Hopkins uses variants of “you” four times, the refrain like a consoling touch of the child’s shoulder. “Unleaving” falls into “leaves.” A question is followed with another question, though the second is directed more towards the reader, who might be the real subject of this poem.

That questioning of the reader is the first reason why Hopkins’s poem stays with me. I think the best poetry is a form of interrogation of self. I can move through much of my public day hearing language emptied of its soul by politicians and twisted into service by advertising. But I pray that poetry props-up language. I don’t think language always needs to be resuscitated through a melancholic mode. Michael Robbins smacks poetic language back into life through humor (“I am small, / I contain platitudes.”), but melancholy is particularly well-suited toward a poetry of permanence.

Ah! ás the heart grows older

It will come to such sights colder

By and by, nor spare a sigh

Though worlds of wanwood leafmeal lie;

And yet you wíll weep and know why.

Poetry makes us children again. That might sound incompatible with the stereotypical image of young students in rows, searching for meanings that poets never intended, but many of our earliest and most profound experiences with language have been when it is delivered within a poetic mode. The wrenching crux of “Spring and Fall” is that Margaret is you and I. She is my twin daughters, who, barely over a year, speak in cries more than words. It makes me think of the intellectual complexity of parenthood: by loving our children we are also, in some measure, loving ourselves. I don’t want my daughters to ever be sad. It is an unrealistic hope, because “worlds of wanwood leafmeal life.” Yet that hope, however tenuous and naïve, is so necessary.

The narrator of “Spring and Fall” wants Margaret — wants us — to know that the ultimate melancholy is the awareness of our mortality. Poems about death are legion, but Hopkins’s careful construction allows his notes to bounce off the other lines. Second-person, when used well, is a wonderful poetic mirror.

Now no matter, child, the name:

Sórrow’s spríngs áre the same.

Nor mouth had, no nor mind, expressed

What heart heard of, ghost guessed:

Poetry’s brevity and tendency toward paradox through interiority of content make it the perfect artistic vehicle for melancholy. We spend our days living and speaking in prose. Poetry is manual transmission. Poetry is an old vehicle made new. In order to read a poem, we must occupy another, more monastic space. In that sense, melancholy is an excellent fit for poetry, since the feeling is an emotional rattling. Novels have hurt me. Stories have punctured my skeptical skin. Essays have made me rethink the world. But a melancholic poem shatters me, pushes me to another emotional space. It extends my self. The brevity of “Spring and Fall” means that this is a powerful but short affair. I can leave the room, and though the words will return as a whisper, I can go back to life. Longer works drown me in their world, so that my reentry into the real one is difficult. But “Spring and Fall” is small enough to fit inside my pocket and under my tongue. Its soft rhythms lull me into accepting the inevitability of its narrative.

It ís the blight man was born for,

It is Margaret you mourn for.

Some readings of “Spring and Fall” criticize the tendency of the speaker and other “colder,” adult hearts to not be moved by nature. An environmentalist reading would be consistent with Hopkins, who found the entire natural world “charged with the grandeur of God.” Hopkins certainly crafted an imperfect narrator who seems world-wearied, pained. A speaker who is willing to reveal the end of innocence.

A well-placed poem can remind us that our existences are, cosmically, equally as brief as these 15 lines. “Spring and Fall” accumulates toward the heavy conclusion that our truest sadness is the recognition that it is not the falling of leaves that pains us, but our own falls, however public or personal. Although Hopkins held a very particular worldview, “Spring and Fall” knows no exclusive creed, race, gender, or time period. It is a poem about our “blight.” The one we share with those we hate and love. Poetry must sometimes tear us apart before it brings us together. For those reasons, “Spring and Fall” is the saddest poem ever written.

Image Credit: Wikipedia