“Feminism did not need a guilty drunk!”

For years I bought into the old saw that says the second novel is the hardest one to write. It seemed to make sense. When starting out, most writers pour everything from the first 20 (or 30, or 40) years of their lives into their debut novel. It’s only natural that on the second visit to the well, many novelists find it has gone dry.

Stephen Fry, the British writer and actor, explained it this way: “The problem with a second novel is that it takes almost no time to write compared with a first novel. If I write my first novel in a month at the age of 23 and my second novel takes me two years, which one have I written more quickly? The second, of course. The first took 23 years and contains all the experience, pain, stored-up artistry, anger, love, hope, comic invention and despair of a lifetime. The second is an act of professional writing. That is why it is so much more difficult.”

Fry made these remarks at the inaugural awarding of the Encore Prize, established in England in 1989 to honor writers who successfully navigate the peculiar perils of the second novel. Winners have included Iain Sinclair, Colm Toibin, A.L. Kennedy, and Claire Messud.

Fry’s point is well taken, but it’s just the beginning of the difficulties facing the second novelist. If a first novel fails to become a blockbuster, as almost all of them do, publishers are less inclined to get behind the follow-up by a writer who has gained a dubious track record but has lost that most precious of all literary selling points: novelty. Writers get only one shot at becoming The Next Big Thing, which, to too many publishers, is The Only Thing. Failure to do so can carry a wicked and long-lasting sting.

(Full disclosure: I’m speaking from experience. My first novel enjoyed respectable sales and a gratifying critical reception, including a largely positive review from impossible-to-please Michiko Kakutani in The New York Times. But the novel failed to land on any best-seller lists or get me on Oprah. Five years later, my second novel disappeared like a stone dropped in a lake. I don’t think anyone even noticed the splash. I recently sold my third novel — 17 years after that quiet splash.)

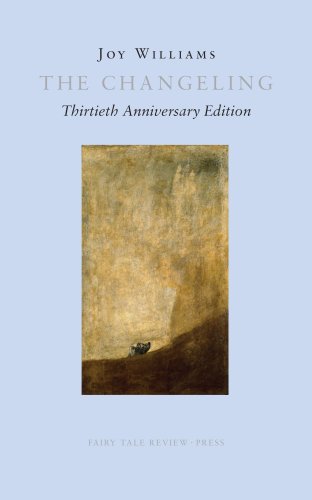

There’s plenty of empirical evidence to support the claim that the second novel is the hardest one to write — and that it can be even harder to live down. After his well-received 1988 debut, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, Michael Chabon spent years wrestling with a woolly, 1,500-page beast called The Fountain that finally defeated him and wound up in a drawer. Wisely, Chabon went in a different direction and produced Wonder Boys, a successful second novel that was, technically, his third. After getting nominated for a National Book Award for her 1973 debut, State of Grace, Joy Williams puzzled and pissed-off a lot of people with The Changeling, her unsettling second novel about a drunk woman on an island full of feral kids. Williams blamed the book’s frosty reception on the political climate of the late 1970s: “Feminism did not need a guilty drunk!” Martin Amis followed his fine debut, The Rachel Papers, with the disappointingly flippant Dead Babies. I still find it hard to believe that the writer responsible for Dead Babies (and an even worse wreck called Night Train) could also be capable of the brilliant London Fields, Time’s Arrow, The Information and, especially, Money: A Suicide Note. Then again, outsize talent rarely delivers a smooth ride. Even Zadie Smith stumbled with The Autograph Man after her acclaimed debut, White Teeth.

There’s plenty of empirical evidence to support the claim that the second novel is the hardest one to write — and that it can be even harder to live down. After his well-received 1988 debut, The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, Michael Chabon spent years wrestling with a woolly, 1,500-page beast called The Fountain that finally defeated him and wound up in a drawer. Wisely, Chabon went in a different direction and produced Wonder Boys, a successful second novel that was, technically, his third. After getting nominated for a National Book Award for her 1973 debut, State of Grace, Joy Williams puzzled and pissed-off a lot of people with The Changeling, her unsettling second novel about a drunk woman on an island full of feral kids. Williams blamed the book’s frosty reception on the political climate of the late 1970s: “Feminism did not need a guilty drunk!” Martin Amis followed his fine debut, The Rachel Papers, with the disappointingly flippant Dead Babies. I still find it hard to believe that the writer responsible for Dead Babies (and an even worse wreck called Night Train) could also be capable of the brilliant London Fields, Time’s Arrow, The Information and, especially, Money: A Suicide Note. Then again, outsize talent rarely delivers a smooth ride. Even Zadie Smith stumbled with The Autograph Man after her acclaimed debut, White Teeth.

Sometimes a hugely successful — or over-praised — first novel can be a burden rather than a blessing. Alex Garland, Audrey Niffenegger, Charles Frazier, and Donna Tartt all enjoyed smash debuts, then suffered critical and/or popular disappointments the second time out. Frazier had the consolation of getting an $8 million advance for his dreadful Thirteen Moons, while Niffenegger got $5 million for Her Fearful Symmetry. That kind of money can salve the sting of even the nastiest reviews and most disappointing sales. Tartt regained her footing with her third novel, The Goldfinch, currently the most popular book among readers of The Millions and a few hundred thousand other people.

Sometimes a hugely successful — or over-praised — first novel can be a burden rather than a blessing. Alex Garland, Audrey Niffenegger, Charles Frazier, and Donna Tartt all enjoyed smash debuts, then suffered critical and/or popular disappointments the second time out. Frazier had the consolation of getting an $8 million advance for his dreadful Thirteen Moons, while Niffenegger got $5 million for Her Fearful Symmetry. That kind of money can salve the sting of even the nastiest reviews and most disappointing sales. Tartt regained her footing with her third novel, The Goldfinch, currently the most popular book among readers of The Millions and a few hundred thousand other people.

A handful of writers never produce a second novel, for varied and deeply personal reasons. Among the one-hit wonders we’ve written about here are James Ross, Harper Lee, Margaret Mitchell, and Ralph Ellison. And in certain rare cases, the second novel is not only the hardest one to write, it’s the last one that gets written. Consider Philip Larkin. He published two highly regarded novels, Jill and A Girl in Winter, back to back in the 1940s — and then abruptly abandoned fiction in favor of poetry. Why? Clive James offered one theory: “The hindsight answer is easy: because he was about to become the finest poet of his generation, instead of just one of its best novelists. A more inquiring appraisal suggests that although his aesthetic effect was rich, his stock of events was thin…Larkin, while being to no extent a dandy, is nevertheless an exquisite. It is often the way with exquisites that they graduate from full-scale prentice constructions to small-scale works of entirely original intensity, having found a large expanse limiting.” In other words, for some writers the biggest canvas is not necessarily the best one.

Of course, second novels don’t always flop — or drive their creators away from fiction-writing. Oliver Twist, Pride and Prejudice, Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa, Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49, and John Updike’s Rabbit, Run are just a few of the many second novels that were warmly received upon publication and have enjoyed a long shelf life. But until about a year ago, I regarded such stalwarts as the exceptions that proved the rule. Then a curious thing happened. I came upon a newly published second novel that knocked me out. Then another. And another. In all of these cases, the second novel was not merely a respectable step up from a promising debut. The debuts themselves were highly accomplished, critically acclaimed books; the second novels were even more ambitious, capacious, and assured.

I started to wonder: With so much high-quality fiction getting written every day in America — especially by writers who are supposed to be in the apprentice phase of their careers — is it possible that we’re entering a golden age of the second novel? Here are three writers who make me believe we are:

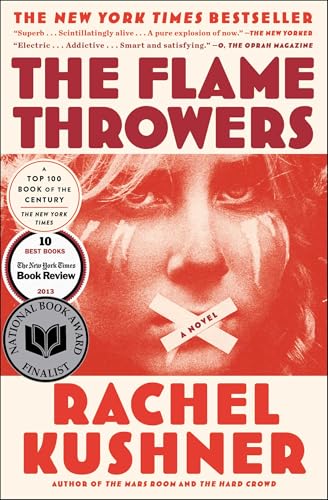

Rachel Kushner

Rachel Kushner’s 2008 debut, Telex from Cuba, was a finalist for the National Book Award. Refreshingly free of the mirror-gazing that mars many first novels, it told the story of two insulated colonies in the eastern end of Cuba in the late 1950s, where Americans were blithely extracting riches from sugar crops and nickel deposits while Fidel Castro and his rebels were getting ready to sweep away the corrupt regime of Fulgencio Batista — and, with it, the Americans’ cloistered world.

Rachel Kushner’s 2008 debut, Telex from Cuba, was a finalist for the National Book Award. Refreshingly free of the mirror-gazing that mars many first novels, it told the story of two insulated colonies in the eastern end of Cuba in the late 1950s, where Americans were blithely extracting riches from sugar crops and nickel deposits while Fidel Castro and his rebels were getting ready to sweep away the corrupt regime of Fulgencio Batista — and, with it, the Americans’ cloistered world.

The novel is richly researched and deeply personal. Kushner’s grandfather was a mining executive in Cuba in the 1950s, and her mother grew up there. Kushner interviewed family members, pored over their memorabilia, even traveled to Cuba to walk the ground and talk to people who remembered life before the revolution. To her great credit, Kushner’s imagination took precedence over her prodigious research as she sat down to write. As she told an interviewer, “Just because something is true doesn’t mean it has a place.”

While her debut took place inside a hermetically sealed cloister, Kushner’s second novel, The Flamethrowers, explodes across time and space. The central character is Reno, a young woman from the West hoping to break into the 1970s downtown New York art scene, a motorcycle racer with “a need for risk.” But Reno’s artistic aspirations are merely the springboard for this ambitious novel as it moves from the 1970s to the First World War, from America to Europe to South America. It teems with characters, events, voices, ideas. It’s a big, sprawling, assured novel, and it announced the arrival of a major talent.

Jonathan Miles

Dear American Airlines, Jonathan Miles’s first novel, exists in an even more tightly circumscribed space than Kushner’s American enclave in pre-revolutionary Cuba. This novel takes place inside the American Airlines terminal at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport — or, more accurately, inside the brain of Benjamin R. Ford, who has been stranded at O’Hare while trying to fly from New York to Los Angeles to attend the wedding of his gay daughter and, just maybe, reverse the downward momentum of a magnificently botched life. The novel’s conceit is a beauty: furious and utterly powerless, Ben, a failed poet, a failed drunk, a failed husband and father — but a reasonably successful translator — decides to sit down and write a complaint letter, demanding a refund from the soulless corporation that has kept him from attending his daughter’s wedding, effectively thwarting his last chance at redemption. The conceit could have turned the novel into a one-trick pony in less capable hands, but Miles manages to make Ben’s plight emblematic of what it’s like to live in America today — trapped and manipulated by monstrous forces but, if you happen to be as funny and resourceful as Ben Ford, never defeated by them.

Dear American Airlines, Jonathan Miles’s first novel, exists in an even more tightly circumscribed space than Kushner’s American enclave in pre-revolutionary Cuba. This novel takes place inside the American Airlines terminal at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport — or, more accurately, inside the brain of Benjamin R. Ford, who has been stranded at O’Hare while trying to fly from New York to Los Angeles to attend the wedding of his gay daughter and, just maybe, reverse the downward momentum of a magnificently botched life. The novel’s conceit is a beauty: furious and utterly powerless, Ben, a failed poet, a failed drunk, a failed husband and father — but a reasonably successful translator — decides to sit down and write a complaint letter, demanding a refund from the soulless corporation that has kept him from attending his daughter’s wedding, effectively thwarting his last chance at redemption. The conceit could have turned the novel into a one-trick pony in less capable hands, but Miles manages to make Ben’s plight emblematic of what it’s like to live in America today — trapped and manipulated by monstrous forces but, if you happen to be as funny and resourceful as Ben Ford, never defeated by them.

It was a deft performance, but Miles outdid it last year with his second novel, Want Not, a meditation on the fallout of omnivorous consumerism. It tells three seemingly unrelated stories that come together only at the novel’s end: Talmadge and Micah, a couple of freegan scavengers, are squatting in an abandoned apartment on the New York’s Lower East Side, living immaculately pure lives off the grid; Elwin Cross Jr., a linguist who studies dying languages, lives alone miserably in the New Jersey suburbs, regularly visiting the nursing home where his father is succumbing to Alzheimer’s; and Dave Masoli, a bottom-feeding debt collector, his wife Sara, whose husband was killed on 9/11, and her daughter Alexis, who brings the strands of the story together, in shocking fashion.

It was a deft performance, but Miles outdid it last year with his second novel, Want Not, a meditation on the fallout of omnivorous consumerism. It tells three seemingly unrelated stories that come together only at the novel’s end: Talmadge and Micah, a couple of freegan scavengers, are squatting in an abandoned apartment on the New York’s Lower East Side, living immaculately pure lives off the grid; Elwin Cross Jr., a linguist who studies dying languages, lives alone miserably in the New Jersey suburbs, regularly visiting the nursing home where his father is succumbing to Alzheimer’s; and Dave Masoli, a bottom-feeding debt collector, his wife Sara, whose husband was killed on 9/11, and her daughter Alexis, who brings the strands of the story together, in shocking fashion.

From the first pages, it’s apparent that the themes are large, the characters are vivid and complex (with the exception of Dave Masoli), and the prose is rigorously polished. Here’s one of many astonishing sentences, a description of what Elwin hears after he has accidentally struck and killed a deer while driving home late at night:

It took a few seconds for the panicked clatter in his head to subside, for the hysterical warnings and recriminations being shouted from his subcortex to die down, and then: silence, or what passes for silence in that swath of New Jersey: the low-grade choral hum of a million near and distant engine pistons firing through the night, and as many industrial processes, the muted hiss and moan of sawblades and metal stamps and hydraulic presses and conveyor belts and coalfired turbines, plus the thrum of jets, whole flocks of them, towing invisible contrails toward Newark, and the insectile buzz of helicopters flying low and locust-like over fields of radio towers and above the scrollwork of turnpike exits, all of it fused into a single omnipresent drone, an aural smog that was almost imperceptible unless you stood alone and quivering on a deserted highwayside in the snow-hushed black hours of a November morning with a carcass hardening in the ice at your feet.

Want Not is a profound book not because Miles preaches, not even because he understands that we are what we throw away, but because he knows that our garbage tells us everything we need to know about ourselves, and it never lies.

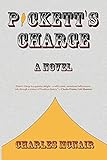

Charles McNair

In 1994, Charles McNair’s weird little first novel, Land O’ Goshen, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. It reads as if it were written by Faulkner on acid. It’s corn-pone sci-fi. It’s nasty and funny. It’s brilliant.

In 1994, Charles McNair’s weird little first novel, Land O’ Goshen, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. It reads as if it were written by Faulkner on acid. It’s corn-pone sci-fi. It’s nasty and funny. It’s brilliant.

The title conjures two locales: the place in Egypt where the Israelites began their exodus to the Promised Land; and the place where the novel unfolds, a little one-blinking-light grease stain in the piney wastes of southern Alabama. The story is told by Buddy, a 14-year-old orphan who lives in the woods, dodging the Christian soldiers who are trying to subjugate the populace. This future era is called the New Times, but it’s a lot like the Old Testament — bloody tooth and bloody claw. Sometimes Buddy dresses up in animal skins and, as The Wild Thing, terrorizes the locals, trying “to wake up those tired, beaten-down old souls in every place where folks just gave up to being stupid and bored and commanded.” Buddy enjoys a brief idyll at his forest hideout with a beautiful girl named Cissy Jean Barber, but the world won’t leave them in peace. Through the nearly Biblical tribulations of his coming of age, Buddy learns the key to survival: “Sad sorrow can’t kill you, if you don’t let it.”

Last year, after nearly two decades of silence, McNair finally published his second novel, Pickett’s Charge. It’s bigger than its predecessor in every way. It traverses an ocean, a century, a continent. If Land O’ Goshen was content to be a fable, Pickett’s Charge aspires to become a myth. It tells the story of Threadgill Pickett, a former Confederate soldier who, at the age of 114 in 1964, is a resident of the Mobile Sunset Home in Alabama. As a teenage soldier, Threadgill watched Yankees murder his twin brother, Ben, a century earlier, and when Ben’s ghost appears at the nursing home to inform Threadgill that he has located the last living Yankee soldier, a wealthy man in Bangor, Maine, Threadgill embarks on one last mission to avenge his brother’s death.

Last year, after nearly two decades of silence, McNair finally published his second novel, Pickett’s Charge. It’s bigger than its predecessor in every way. It traverses an ocean, a century, a continent. If Land O’ Goshen was content to be a fable, Pickett’s Charge aspires to become a myth. It tells the story of Threadgill Pickett, a former Confederate soldier who, at the age of 114 in 1964, is a resident of the Mobile Sunset Home in Alabama. As a teenage soldier, Threadgill watched Yankees murder his twin brother, Ben, a century earlier, and when Ben’s ghost appears at the nursing home to inform Threadgill that he has located the last living Yankee soldier, a wealthy man in Bangor, Maine, Threadgill embarks on one last mission to avenge his brother’s death.

Pickett’s Charge has obvious echoes – the Bible, Twain, Cervantes, Marquez, Allan Gurganus’s Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All. But this novel’s most direct forebear might be Charles Portis’s Norwood, another story about a southerner’s quixotic journey to the North to seek justice. While Threadgill Pickett is after something big — vengeance — Norwood Pratt is simply out to collect the $70 he loaned a buddy in the Marines. Yet McNair and Portis seem to agree that folly is folly, regardless of its scale. And they both know how to turn it into wicked fun.

Of course one could argue that a half dozen books do not constitute a trend or herald a new golden age. But I’m sure I’ve missed a truckload of recent second novels that would buttress my claim. Maybe Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation, which has come out 15 years after her debut and is concerned, in part, with the difficulty of writing a second novel. Surely there are others that disprove the old saw. I would love it if you would tell me about them.

Image Credit: Wikipedia