This piece was produced in partnership with Bloom, a new site that features authors whose first books were published when they were 40 or older.

1.

1.

If ever there was a writer disappointed with the here and now, it’s André Aciman. Best-known for evoking the lost Alexandria of his childhood, Aciman writes in a recent essay:

Things that do not have an Egyptian analog do not register, have no narrative. Things that happen in the present without echoing even an imaginary past do not register either. They cease to exist. They do not count.

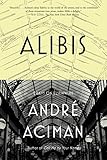

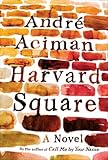

In an interview in the Los Angeles Review of Books, he underscores this perpetual dissatisfaction even more strongly: “I was never in one place, ever, in my whole life, without thinking of being somewhere else.” The tragedy of feeling out of place and in the wrong time is at the aching heart of Aciman’s writing, and on grand display in two new books published this year: Alibis: Essays on Elsewhere and his third novel, Harvard Square. The tragedy of his displacement, however, does not create victims. Aciman’s narrators are disappointed not only in the world before them but also in themselves.

In an interview in the Los Angeles Review of Books, he underscores this perpetual dissatisfaction even more strongly: “I was never in one place, ever, in my whole life, without thinking of being somewhere else.” The tragedy of feeling out of place and in the wrong time is at the aching heart of Aciman’s writing, and on grand display in two new books published this year: Alibis: Essays on Elsewhere and his third novel, Harvard Square. The tragedy of his displacement, however, does not create victims. Aciman’s narrators are disappointed not only in the world before them but also in themselves.

He has been hailed as a writer who excels in the investigation of memory, but it’s not a fixed past that offers the siren’s call; it is a past that dreams of and anticipates a future full of longing for itself. The act that goes by the name of remembering in Aciman’s world is actually a process of invention and loose reconstruction whose appeal is the formation of a coherent narrative of desires. Most of us would say “experience” is the fabric of our lives, but for Aciman it’s the desire that motivates experience, and that remains after the fact, that constitutes our identity. “The disconnect, the hiatus, the tiny synapse — call it once again the spread between us and time, between who we are and wish we might have been — is all we have to understand our place in life,” he writes. “One measures time not in units of experience but in increments of hope and anticipated regret.” What do we long for and why? This is what Aciman wants to know.

2.

Born in 1951, Aciman lived his first 14 years in Alexandria, Egypt, among a multinational, multilingual, and multigenerational Jewish family of educated entrepreneurs. Shortly after his birth the Egyptian monarchy was overthrown, followed by the Suez Canal Crisis in 1956, in which Israel, joined by Britain and France, invaded Egypt to reverse President Nasser’s nationalization of the Canal. After Israel’s attack, Jews were no longer welcome in Egypt. When Aciman’s uncle was arrested on the night of the author’s great-grandmother’s 100th birthday, nervous relatives began to flee to the world’s Western corners. Aciman’s own parents lasted until 1965, when his father’s profitable textile mill was nationalized. The family then fled to Rome, where they lived for three years while waiting for visas to the United States. In 1968 he moved, with his parents and brother, to New York City.

Aciman calls himself a late bloomer as a writer, pointing first to the fact that he didn’t start until the fifth or sixth grade and, more significantly, to how long it took him to develop an American, non-academic style and sensibility. Aciman grew up speaking primarily French, with Italian, Greek, English, Ladino (the Spanish-like language of Sephardic Jews), and Arabic mixed in. His boyhood schooling was stark and unhappy, marked by poor teaching and the humiliation of corporal punishment. (In the era of nationalization, Aciman’s flunking Arabic class was of great consternation to his father, who believed his son’s failure would draw retribution from the government.) In America, Aciman’s academics improved considerably, and he eventually earned a doctorate in comparative literature from Harvard. But he soon found his academic career limiting. He began writing book reviews for Commentary, whose editor he asked if he could write something for the magazine about growing up Jewish in Alexandria.

3.

Aciman’s debut book, the exceptional memoir Out of Egypt, was published in 1995, when he was 44. The book traces his family’s Alexandrian life from 1905 to 1965, telling the stories of various aunts and uncles in exciting, up-close detail, even though the events take place up to 50 years before the author’s birth. “Gossip is, for me, a fount of information superior to history,” he says. The young Aciman is fought over by his two grandmothers, the Princess and the Saint, and absorbs the rigid class and cultural distinctions resulting from the fact that his mother’s father is an Aleppo-born Syrian Jew. The European Sephardi side of the family attempts constant rescue of the young boy from the uncouth ways of “the Arabs.” The prose is beautifully fluid and elegiac throughout without being in the least sentimental, and the book’s scenes unfold like a play I could watch for hours, not caring so much about the story but captivated by the pride, sorrow, invective, and determined survival of this family and their friends and servants.

Aciman’s debut book, the exceptional memoir Out of Egypt, was published in 1995, when he was 44. The book traces his family’s Alexandrian life from 1905 to 1965, telling the stories of various aunts and uncles in exciting, up-close detail, even though the events take place up to 50 years before the author’s birth. “Gossip is, for me, a fount of information superior to history,” he says. The young Aciman is fought over by his two grandmothers, the Princess and the Saint, and absorbs the rigid class and cultural distinctions resulting from the fact that his mother’s father is an Aleppo-born Syrian Jew. The European Sephardi side of the family attempts constant rescue of the young boy from the uncouth ways of “the Arabs.” The prose is beautifully fluid and elegiac throughout without being in the least sentimental, and the book’s scenes unfold like a play I could watch for hours, not caring so much about the story but captivated by the pride, sorrow, invective, and determined survival of this family and their friends and servants.

In a gorgeous essay called “Intimacy” in his 2013 collection Alibis, Aciman returns with his wife and sons to the apartment in working-class Rome where his family lived during their three years of visa-limbo. His approach to the old place is sly, strategic, timed to build just the right amount of apprehensive anticipation; he has avoided returning for a reason:

I had always been ashamed of Via Clelia, of its good people, ashamed of having lived among them, ashamed of myself now for feeling this way, ashamed, as I told my sons, of how I’d always misled my private-school classmates into thinking I live “around” the affluent Appia Antica.

He describes shame as “the reluctance to be who we’re not even sure we are” and suggests it “could end up being the deepest thing about us, deeper even than who we are, as though beyond identity were buried reefs and sunken cities teeming with creatures we couldn’t begin to name because they came long before us.” To get around this shame, Aciman dissembles, faking how he felt then and how he feels now. He tells his sons with false disaffection: “Fancy spending three years in this dump.” He doesn’t let on how much he wants to be injected by the past. The memory of his former, vulnerable self in this ancient city — in this bursting-with-character neighborhood — should move him, shouldn’t it? But the dissembling, both then and now, is successful, which leads to an unintended side effect: he’s untouched by the return. He looks around, sees, recognizes, but feels nothing. The present has failed him.

Later in the day, Aciman returns in his mind to Via Clelia and tries to sort out the visit by writing about it, hoping the process will “un-numb” him and bolster the event with “retrospective resonance.” Of course, as soon as he has recorded this hope, he doubts such a thing is possible. Instead of revealing, he asks, does writing “provide surrogate pleasures the better to numb us to experience?” His lack of response to the place leaves him wondering if some part of him has permanently disappeared; or perhaps his former self was merely a shadow. The majority of Aciman’s Rome years were spent reading in his bedroom — Lampedusa, Baudelaire, Dostoevsky, Wordsworth, Joyce. These fictions papered over the daily misery of his exile, and now, when he revisits with his wife and sons, Aciman realizes that “all I’d been able to cull here were the fictions, the lies I’d laid down upon this street to make it habitable. Dreammaking and dissemblance, then as now.”

“Intimacy” is signature Aciman, an essay that originates with a pilgrimage and rushes headlong into the past in expectation of a revelation that never comes — that cannot come. He dives into the current of memory to fetch a dropped object only to surface many yards downstream triumphantly upholding a prize similar, but not identical, to what was lost. He is not fooled, though. He knows the object never existed, but it is far more interesting to write about a failed search after the fact than to admit at the beginning that such an attempt is futile.

4.

Such reflections on the influence of writing on experience are layered throughout Alibis, as are musings on the empathetic and escapist activity of reading. Aciman is a devout classicist with little patience for contemporary writing, and it should come as no surprise that Proust is of paramount importance to him. In “Temporizing,” Aciman assigns the French time-seeker a verb tense all his own, the imperfect-conditional-anterior-preterit (a concept I’ve explored in The Common), and Proust’s more general influence — especially in his labyrinthine sentences — threads throughout his work.

As in Proust, a richly sensory world swirls and flares around the figure I have come to think of as “the Aciman narrator” — the voice of his essays and the unnamed first-person narrator of Harvard Square. Through the sun-washed beach of the Lido in Venice, the ocher walls and refuse of Roman alleys, the lavender scent of a snug Old World, Middle Eastern living room, and the wooded sunshine of Walden Pond, Aciman’s worlds are vivid and particular. However, on closer look, even these descriptions reveal his distance from the moment. Rereading “Intimacy,” I was surprised to see that the “frail street singer [who] would stand every afternoon and bellow out bronchial arias you strained to recognize” was a tune pulled from the past; very little of Via Clelia at the moment of his return makes it onto the page. The wonderful Walden Pond scene in Harvard Square hardly features the place, but rather the effect of the larger-than-life central character, Kalaj, on the narrator and the foreign au pairs who accompany them for a swim. Sensory experience is only the premise upon which deeper emotional and psychological investigations are built.

Aciman’s places — mostly cities—are projections, patinas he perfectly calls “wishfilms.” He doesn’t know the Rome of 1965-68 as it really existed, only as he dreamed it then and has chosen to remember now. But this shouldn’t matter. Who cares about the actual street sequence of shops or the exact words of a conversation?

We seldom ever see, or read, or love things as they in themselves really are, nor, for that matter, do we even know our impressions of them as they really are. What matters is knowing what we see when we see other than what lies before us. It is the film we see, the film that breathes essence into otherwise lifeless objects, the film we crave to share with others.

So it is with the narrator of Harvard Square, the reclusive, evasive graduate student of literature inevitably drawn to the brash swagger of a libidinous Arab. In addition to his relentless pursuit of women, Kalaj — short for Monsieur Kalashnikov, after his rat-a-tat diatribes — is forever slicing up the world in hugely enjoyable rants. All of America is “jumbo-ersatz,” he says, from its peroxide blondes with boob jobs to its love of nectarines, an overly fleshy, hybrid fruit that is “all graft” and therefore cannot reproduce.

Having both grown up in Arabic North Africa, the two men have a natural affinity: “There was something in the timbre and inflection of his words that seemed to rummage through a clutter of ancestral fragments to remind me of the person I may have been born to be but had not become.” This shared history allows the narrator, for a while, to hand over to Kalaj the responsibility of making sense of his new world. The intimacy of the two men is real, necessary, and yet the graduate student and the illegal taxi driver are worlds apart:

I have a green card, he a driver’s license. He saw the precipice every day of his life, I never had to look down that deep….But there was another difference between us: he knew how to wiggle his way around the precipice; I, however, put him right between the precipice and me. He was my screen, my mentor, my voice. Perhaps his was a life I was desperate to try out.

In the end, the narrator cannot uphold the bonds of friendship. He wants intimacy but not the obligation that could compromise his own ambitions. He is, of course, ashamed of Kalaj, about what an alliance with this brash, vulgar man says about not only the narrator’s origins but who he is now, who he will become.

5.

Beyond any particular exodus or return, it is Aciman’s prose — the rants and curses, the Proust-like rushing forward, diving down, and doubling back — that carries the reader urgently through Alibis and Harvard Square. As he has said about his own writing, even more than finding a kind of comfort zone through literature, he has built the lifeboat that ferries him from shore to foreign shore with cadence:

Cadence is like feeling, and cadence is like breathing, and cadence is heartbeat and desire, and if cadence doesn’t reinvent everything we would like our life to have been or to become, then just the act of searching and probing in that particularly cadenced way becomes a way of feeling and of being in the world.

For Aciman, we will be in the world tomorrow. Today we will write about the dreamed-up past.