In the fifth episode of the hit sitcom New Girl, a self-styled stud tries to impress an Indian-American woman by declaring that he loves India. When pressed for details, he stumbles his way through the following catalogue:

I love Slumdog. I love naan. I love pepper. I love Ben Kingsley, the stories of Rudyard Kipling. I have respect for cows, of course. I love the Taj Mahal, Deepak Chopra, anyone named Patel. I love monsoons. I love cobras in baskets…I love mango chutney, really, any type of chutney.

The point is clear: the average American’s knowledge of Indian culture is superficial, stereotypical, and offensive. Nevertheless, the mere existence of the joke — and an Indian-American woman in a leading role on primetime TV — confirms how much Indian culture has permeated American pop culture. This should not be surprising: With a population that increased to 2.8 million from 1.7 million between 2000 and 2010, Indians are one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in America. They may also be one of the fastest growing ethnic groups in literary fiction — in America and the larger Anglophone world.

Fiction written in English by authors of Indian descent has been critically acclaimed and commercially successful for decades. Now a new wave of talent has arrived: In 2012, the Indian-American writers Rajesh Parameswaran and Tania James published their debut short story collections — I Am An Executioner: Love Stories and Aerogrammes, respectively — while British-Indian author Hari Kunzru published his fourth novel, Gods Without Men: While it may be too soon for these authors to have achieved the heavyweight status of a Salman Rushdie or Jhumpa Lahiri, their imaginative, provocative, and well-crafted books suggest the continuation of a literary legacy and a move into “post-post-colonial,” “post-ethnic” territory.

Fiction written in English by authors of Indian descent has been critically acclaimed and commercially successful for decades. Now a new wave of talent has arrived: In 2012, the Indian-American writers Rajesh Parameswaran and Tania James published their debut short story collections — I Am An Executioner: Love Stories and Aerogrammes, respectively — while British-Indian author Hari Kunzru published his fourth novel, Gods Without Men: While it may be too soon for these authors to have achieved the heavyweight status of a Salman Rushdie or Jhumpa Lahiri, their imaginative, provocative, and well-crafted books suggest the continuation of a literary legacy and a move into “post-post-colonial,” “post-ethnic” territory.

Parameswaran, James, and Kunzru inherit three decades of Anglo-Indian literary success. Rushdie’s magical realist novel Midnight’s Children, about a boy born on the precise moment of Indian Independence, won the Man Booker Prize, the U.K.’s most prestigious literary award. His most notorious novel The Satanic Verses earned Rushdie a death threat from Ayatollah Khomeini that sparked international controversy and massive sales, an experience upon which he reflects in his memoir Joseph Anton, recently excerpted in The New Yorker. In recent years, the Booker has gone to Arundati Roy’s novel The God of Small Things and Aravind Adiga’s novel The White Tiger, a hybrid of Invisible Man and Native Son set on the subcontinent. And as recently announced, the six authors shortlisted for the 2012 Booker includes Jeet Thayil, born in India, raised in Hong Kong, India and the U.S., and the author of the novel Narcopolis, about a 1970s opium den.

Parameswaran, James, and Kunzru inherit three decades of Anglo-Indian literary success. Rushdie’s magical realist novel Midnight’s Children, about a boy born on the precise moment of Indian Independence, won the Man Booker Prize, the U.K.’s most prestigious literary award. His most notorious novel The Satanic Verses earned Rushdie a death threat from Ayatollah Khomeini that sparked international controversy and massive sales, an experience upon which he reflects in his memoir Joseph Anton, recently excerpted in The New Yorker. In recent years, the Booker has gone to Arundati Roy’s novel The God of Small Things and Aravind Adiga’s novel The White Tiger, a hybrid of Invisible Man and Native Son set on the subcontinent. And as recently announced, the six authors shortlisted for the 2012 Booker includes Jeet Thayil, born in India, raised in Hong Kong, India and the U.S., and the author of the novel Narcopolis, about a 1970s opium den.

The new wave is also indebted to Lahiri, who rocked the American lit establishment — and book clubs nationwide — with Interpreter of Maladies, an understated, pitch-perfect short story collection that captured the domestic dramas and existential malaise of upper class Indian Americans, mostly in bourgeois Boston. The book won the Pulitzer Prize and was followed by the novel, The Namesake, later a Mira Nair-directed movie, and Unaccustomed Earth, another stunning and more ambitious story collection that cemented Lahiri’s reputation as the marquee Indian-American fiction writer and a master of short fiction.

The new wave is also indebted to Lahiri, who rocked the American lit establishment — and book clubs nationwide — with Interpreter of Maladies, an understated, pitch-perfect short story collection that captured the domestic dramas and existential malaise of upper class Indian Americans, mostly in bourgeois Boston. The book won the Pulitzer Prize and was followed by the novel, The Namesake, later a Mira Nair-directed movie, and Unaccustomed Earth, another stunning and more ambitious story collection that cemented Lahiri’s reputation as the marquee Indian-American fiction writer and a master of short fiction.

Beyond heritage, Parameswaran, Kunzru, and James have similar pedigrees. Parameswaran went to Yale for college and law school, Kunzru went to Oxford, and James went to college at Harvard and grad school at Columbia. (Rushdie went to Cambridge). Too old to be wunderkind, all are still young by literary standards: James is 31, Parameswaran is 40, and Kunzru is 43. And while they hail from Michigan and Texas, Kentucky, and London, all three now live in the New York area. Perhaps a brunch is in order?

True to their heritage, all three address issues of Indian identity. In the central storyline of Gods, an Indian-American man marries a Jewish-American woman and the incipient tensions in their marriage combust after their son disappears. In “Ethnic Ken,” a story in Aerogrammes, an Indian-American girl plays with a brown-skinned version of Barbie’s boyfriend; the doll apparently cost half the price of the “regular” Ken. In one of the many tragicomic stories in Executioner, an unemployed Indian computer salesman pretends to be a doctor — the paradigmatic profession for high-status Indian Americans — with ghastly consequences. In their treatment of ethnicity, all three books join Lahiri in a subgenre that one of James’s characters, an aspiring screenwriter, calls “not quite Bollywood, not quite Hollywood: Indians in America or England Torn Between Identities.”

Nevertheless, all three authors transcend the stereotypical expectations of “ethnic” fiction, including the notion that characters must share their author’s ethnicity.

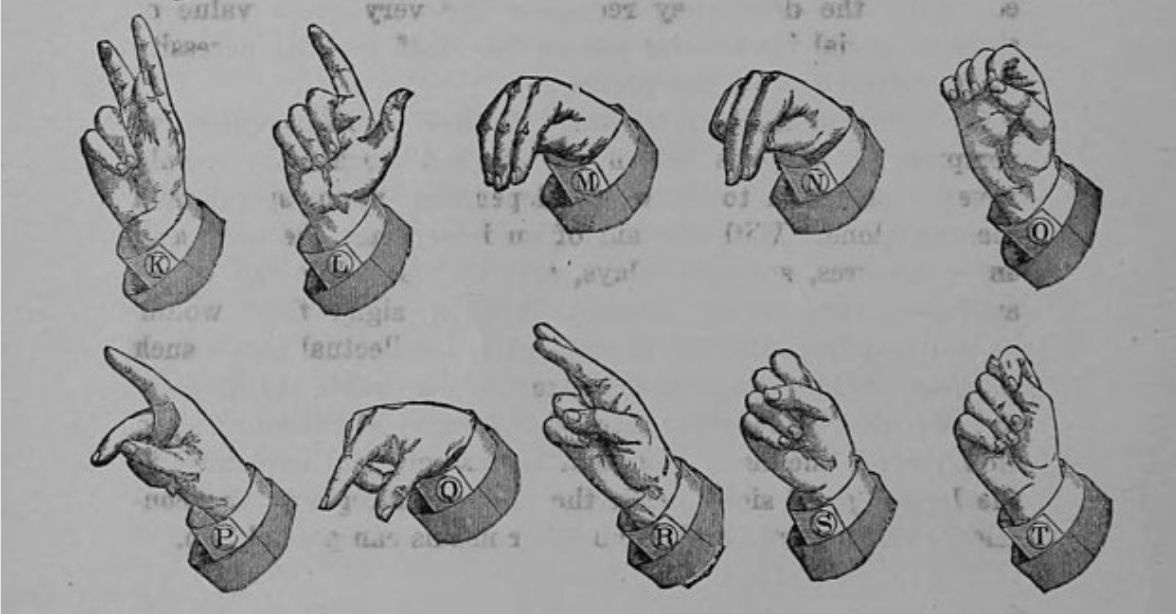

Several stories in Executioner and Aerogrammes feature non-Indian characters. And the Indian-American protagonist in Gods shares a stage with non-Indians including an 18th-century Spaniard, a 19th-century Mormon, and a contemporary (Caucasian) British rock star. Even among the Indian characters, there is diversity: James’s Indian characters speak Malayalam, the language of the state of Kerala, Kunzru’s Indian characters speak Punjabi, spoken in northwestern India and eastern Pakistan, and Parameswaran’s titular executioner speaks in a parody of Indian-accented English: “Normally in the life, people always marvel how I am maintaining cheerful demeanors.” Such simple differences may remind Western readers that India is a multi-ethnic, multi-religious, polyglot and internationally engaged country, not a monolithic, homogenous, insular place.

As if to distance themselves from ethnicity and nationality, all three authors experiment with non-human characters. The narrator of one story in Executioner is an elephant; another is a murderous, guilt-stricken tiger, a literal version of Adiga’s titular “white tiger.” A story in Aerogrammes concerns a chimpanzee that nearly convinces a woman he is human. Strangest of all, Gods opens with a cryptic fable with characters named Cottontail Rabbit, Gila Monster, Southern Fox, and the protagonist Coyote, who sets up a meth lab in the desert. Take that, Kipling.

Regardless of species, all three books grapple with physical, emotional, and existential despair, albeit in different tones and moods. Gods is cerebral, somber, and grim. As he did in the reverse outsourcing fable Transmission, Kunzru assaults his characters until they break, and relents only after they have lost nearly everything. (For the film, perhaps Werner Herzog or P.T. Anderson could direct?) By contrast, Aerogrammes is sweet, sad, and painfully earnest. Characters are naïve, blind, or delusional, whether it’s the Indian wrestlers who don’t realize the sport is supposed to be fake, or the boy who refuses accept his mother’s new husband. There’s pain suffering in Executioner, too but it’s often undercut by humor or an authorial wink, either implied or in meta-fictional parentheses or footnotes.

Regardless of species, all three books grapple with physical, emotional, and existential despair, albeit in different tones and moods. Gods is cerebral, somber, and grim. As he did in the reverse outsourcing fable Transmission, Kunzru assaults his characters until they break, and relents only after they have lost nearly everything. (For the film, perhaps Werner Herzog or P.T. Anderson could direct?) By contrast, Aerogrammes is sweet, sad, and painfully earnest. Characters are naïve, blind, or delusional, whether it’s the Indian wrestlers who don’t realize the sport is supposed to be fake, or the boy who refuses accept his mother’s new husband. There’s pain suffering in Executioner, too but it’s often undercut by humor or an authorial wink, either implied or in meta-fictional parentheses or footnotes.

While Aerogrammes essentially falls into the category of realist fiction, Parameswaran and Kunzru flirt with other genres. Besides the two talking animal stories, Executioner includes a spy thriller, “Narrative of Agent 974702,” and a science fiction tale, “On the Banks of Table River (Planet Andromeda Galaxy, AD 2319).” Perhaps most fantastical — yet paradoxically most credible — is the cult at the center of Gods, a desert commune that fuses Christianity, Buddhism, New Age, and Alien Worship into an explosive whole. Then again, as Kunzru semi-subtly implies, such a group is not so different than the Europeans who Christianized Native Americans or Mormons who found Zion in the American West.

While fundamentally contemporary, all three books derive depth from history. In Executioner, the meta-fictional tale “Four Rajeshes” concerns a railway clerk in colonial India at the turn of the 20th century and his version of Melville’s Bartleby, the Scrivener. The opening story in Aerogrammes features a pair of Indian wrestlers who arrive in England in 1910 to engage in literal and figurative battles with their colonial overlords. Perhaps because it is a novel, Gods is even more historically ambitious, with a storyline that spans more than 200 years. Ultimately, all three authors use history to transcend personal experience, shattering the expectation that “ethnic” fiction must be autobiographical. In a way, they all respond to the question that Rushdie poses in Joseph Anton when recalling his inspiration for writing The Satanic Verses:

While fundamentally contemporary, all three books derive depth from history. In Executioner, the meta-fictional tale “Four Rajeshes” concerns a railway clerk in colonial India at the turn of the 20th century and his version of Melville’s Bartleby, the Scrivener. The opening story in Aerogrammes features a pair of Indian wrestlers who arrive in England in 1910 to engage in literal and figurative battles with their colonial overlords. Perhaps because it is a novel, Gods is even more historically ambitious, with a storyline that spans more than 200 years. Ultimately, all three authors use history to transcend personal experience, shattering the expectation that “ethnic” fiction must be autobiographical. In a way, they all respond to the question that Rushdie poses in Joseph Anton when recalling his inspiration for writing The Satanic Verses:

The great question of how the world joins up — not only how the East flows into the West and the West into the East but how the past shapes the present even as the present changes our understanding of the past, and how the imagined world, the location of dreams, art, invention, and, yes, faith, sometimes leaks across the frontier separating it from the “real” place in which human beings mistakenly believe they live.

In terms of style and structure, Aerogrammes is the most conventional of the three. The plainspoken prose obeys the aesthetic in which the writer’s voice is secondary to the story. The nine stories are more or less uniform length, each about 20 pages. Ultimately, James seems to value cohesion and consistency over shock and surprise. Parameswaran takes the opposite tack. His voice is always strong and varies widely from story to story; some seem like the work of different authors. If the books were Beatles albums, Aerogrammes would be Rubber Soul, the harmonious whole with songs of essentially equal weight, and Executioner would be The White Album, a hectic hodgepodge of competing voices. (Speaking of The Beatles, didn’t they help bring Indian music and spirituality into Western popular culture?)

Gods splits the difference between these two extremes. Like Executioner, it’s grandiose, sprawling, and dense. With its multiple points of view, multiple settings, and non-linear structure, it often reads like a collection of loosely linked stories. Some plots literally converge; others merely inform each other. Yet over 369 pages, Kunzru maintains cohesion. Part of this may stem from his use of the close third person point of view (which James does in most of her stories). It may also be a matter of experience; perhaps on their fourth books, James and Parameswaran may find a similar balance of ambition and unity.

For all the merits of these books, the question remains: is this literary boomlet an anomaly, a coincidence, or a harbinger? Will these books be a curiosity or a gateway to wider American interest in Indian culture? Will more Indian Americans join Govs. Bobby Jindal and Nikki Haley as high-profile politicians? Will we see more Indians Americans in popular entertainment: TV, movies, sports?

In a poignant scene in Interpreter of Maladies that sums up the cultural barriers at the heart of the book, an American woman tries to buy Hot Mix, an Indian snack. The Indian clerk dismisses her with four words: “Too spicy for you.” Perhaps one day, that scene will seem outmoded, if not unfathomable.