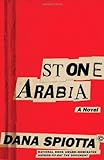

“Do you need an audience to create work or does not having an audience liberate you and make you a truer artist?” This is the question twenty-something Brooklynite Ada poses on her blog before she leaves Greenpoint to interview her eccentric uncle Nik in Los Angeles for the documentary she’s making. Ada’s film will be called Garageland, she writes, and it “will question what makes a person produce in the face of resounding obscurity.” Turn that question inside-out, and it is just as relevant to Stone Arabia, Dana Spiotta’s third novel: How is fame constructed? Do the famous make themselves for us, their fans and consumers, or do we make them? What do their narratives truly represent, and who do their stories belong to?

“Do you need an audience to create work or does not having an audience liberate you and make you a truer artist?” This is the question twenty-something Brooklynite Ada poses on her blog before she leaves Greenpoint to interview her eccentric uncle Nik in Los Angeles for the documentary she’s making. Ada’s film will be called Garageland, she writes, and it “will question what makes a person produce in the face of resounding obscurity.” Turn that question inside-out, and it is just as relevant to Stone Arabia, Dana Spiotta’s third novel: How is fame constructed? Do the famous make themselves for us, their fans and consumers, or do we make them? What do their narratives truly represent, and who do their stories belong to?

Nik is a rockstar, but only a handful of fans — his sister Denise, her daughter Ada, and a small collection of ex-girlfriends and former band-mates — know it. Over the years, Nik has released dozens of LPs to Denise and his few loyal followers, and he’s kept a meticulous record of his career in what he calls the Chronicles, a thirty-volume scrapbook filled with letters, reviews, and other “willful esoteria,” all of his own creation. The rock ’n roll posture gives Nik’s creativity a framework — one that provides cover for his self-destructive habits, but also spurs him to keep producing music long after his early, promising bands fail to make it. For Nik, celebrity is a state of mind.

Nik’s story drives the book’s plot, but it’s Denise who provides Stone Arabia’s narrative lens — and her slow, shapeless days of sorting through bills and checking in on her declining mother couldn’t be further from rock ’n roll. Spiotta writes that the hills of Santa Clarita, the Los Angeles suburb where Denise lives, are “tired” but it seems it is simply Denise who is tired. When Denise begins compiling her own Counterchronicles, her fragmented writings reveal the extent of her mental displacement from her own life. Denise is not an unreliable narrator, but she is clearly an unstable one; there are entire days she can’t account for. She sobs in front of the television while watching the news, and spends hours tunneling through search engine results for more details on the most sensational stories. The ceaseless onslaught of headlines depletes her emotional resources. “It is the feeling that your life has just left the room,” Denise says, broodingly.

In the age of the Internet, when we have an instant portal into the lives (real or imagined) of others through our computers, televisions, and smart-phones, it is a feeling many readers will surely relate to in some form, and this is the novel’s key strength. Stone Arabia’s pull largely lies in its ability to recreate the feeling of media saturation that permeates modern life. Take Denise’s birthday for example:

Ada called me in the morning from New York. She made me promise to look at her blog. She had posted a photo of us and it said, “happy birthday to my mom,” just like that, no caps or anything. Not “happy birthday mom” but “to my mom” because it was really reportage to some audience beyond me. It wasn’t a personal message to me, but a public announcement about me.

Denise stares at her screen for a while; she knows her daughter wants her to post a comment, but she just can’t bring herself to. “I just couldn’t say something spontaneous and pithy and then have it hang there for all eternity,” she thinks. “Those are opposite pulls — eternity and pithy — and if I thought at all about what to say it was even worse.” It’s a familiar dilemma, rendered strangely lyrical through Denise’s eyes. Moments like these repeatedly animate the novel. Again and again, Spiotta perfectly captures the static sound of our televisions and Ethernet cables numbly pumping in more information than we need (or can respond to). And she elegantly depicts the ambivalence this unending electronic stream inspires.

In her debut novel, Lightning Field, Spiotta depicted Los Angeles at its most brutally superficial — and female friendship at its most intimate. This was followed by Eat the Document, a mesmerizing story about a fugitive who reinvents herself in hiding, based on the true story of a real-life 1960s activist and her lover. Stone Arabia is also set in Los Angeles, and is also based on a true story. In the Author’s Note, Spiotta writes that though Nik Worth is a character of her imagination, he’s based her real-life stepfather, “Richard Frasca, a.k.a Jon Denmar. Richard Frasca is not Nik Worth but Richard’s devotion to his own music and Richard’s self-documented chronicle of his life as a secret rock star gave me the idea for Nik.” Most novelists invariably incorporate characters and experiences from their lives into their fiction, but there’s something particularly sly about publishing a work of fiction built off someone else’s semi-ironic, private fiction — particularly when that person is the author’s family member.

In her debut novel, Lightning Field, Spiotta depicted Los Angeles at its most brutally superficial — and female friendship at its most intimate. This was followed by Eat the Document, a mesmerizing story about a fugitive who reinvents herself in hiding, based on the true story of a real-life 1960s activist and her lover. Stone Arabia is also set in Los Angeles, and is also based on a true story. In the Author’s Note, Spiotta writes that though Nik Worth is a character of her imagination, he’s based her real-life stepfather, “Richard Frasca, a.k.a Jon Denmar. Richard Frasca is not Nik Worth but Richard’s devotion to his own music and Richard’s self-documented chronicle of his life as a secret rock star gave me the idea for Nik.” Most novelists invariably incorporate characters and experiences from their lives into their fiction, but there’s something particularly sly about publishing a work of fiction built off someone else’s semi-ironic, private fiction — particularly when that person is the author’s family member.

It’s a fittingly post-modern back-story for a novel which finds each of its main characters trying to make sense of their world through art/music, memoir, and film. Stone Arabia’s tangled layers not-so-subtly mimic the tangled layers of media we all live in. Obsessed with its obsessions (“Even the most pointless obsession can yield a certain kind of depth if it is pursued unfailingly,” Denise thinks), and enchanted by the tension between private and public personas as well as the blurry boundaries between self-documentation and self-creation, Stone Arabia is a truly contemporary novel. Do our stories bring us closer to ourselves, or do they simply hide and splinter our real identity? Stone Arabia assembles an impressive collage of questions about aging, identity, art and its audience, fame and its construction, privacy, knowing and being known, and how we define who we are.

But as the novel slips from third to first person, from Ada’s video transcripts to Nik’s fake-archives, from blog posts to voicemails to movie rentals to search engine results, its narrative coherence meanders. Surely these are deliberate structural choices, but flattened into prose, the onslaught of technology fractures Spiotta’s story-telling. Spiotta is a writer of keen observation and careful craftsmanship, but — though it summons Lightning Field’s cool disaffection and Eat the Document’s enchantment with secret lives and self-invention — Stone Arabia lacks the grace and fluidity of her previous novels. Denise’s recollections from her childhood and early adulthood with Nik are evocative, but they are strung together only tangentially, and none of the book’s secondary characters stick around long enough to matter much. By the end of Stone Arabia, Nik has concluded The Chronicles, Ada has finished Garageland, and Denise has completed her Counterchronicles, but these works offer no real answer or argument to the questions — both stated and understood — that fill their lives. Ultimately, the interruptions of many forms of media — precisely the kinds of interruptions most novels insulate their readers from — give the book a jagged immediacy that raises more questions than it’s capable of answering.