1.

“We’re closing in on a deal,” my agent told me on the phone. “I’m just turning him upside-down now and shaking him for loose change.”

It was midday on a Monday in early August of the year 2000. The Nasdaq, rested from its breather in the spring, was sprinting back up over 4,000 toward its March peak. Vice President Gore, demolishing the Bush son’s early lead, was pulling even in the polls. TV commercials depicted placid investors being wheeled on gurneys into operating rooms, stern-faced doctors diagnosing their patients with dire cases of money coming out the wazoo.

The previous Friday, bidding on my first novel had reached six figures, then paused for people to track down more cash. I’d later learn one editor spent the weekend trying to reach her boss on his Tanzanian vacation, finally getting through via the satellite phone of a safari boat on the Rufiji river, but that he wouldn’t OK a higher bid because he couldn’t get the manuscript in time.

I was 32. I’d never made over $12,000 in a year.

I’d signed on with my agent only a couple of weeks earlier. He was about my age, a clean-cut, preppie-looking guy named Bill, just making the transition from being an assistant to having clients of his own. He’d walked me through an open-floored office, agents and subagents stepping out from behind their iMacs and glass walls to shake my hand. We’d sat down in a sunny conference room, and after a few minutes I knew he was thoroughly attuned to my work; moreover he’d put his finger on a couple of remaining weak points, about which I agreed entirely and was eager to go home and address.

“How soon do you think an editor might read it?” I asked. I’d met with another interested agent a few days before. She’d told me it was the summer and things were slow, but my novel was so good—and so timely—that she knew an editor at Grove she was almost sure would read it in as little as four to six weeks.

Bill looked out the window, thoughtful. “It’s the summer, things are slow. Everyone’s hungry right now. We’ll give them the manuscript to take with them to the Hamptons to read over the weekend. Then the following week, you’ll meet with them and we’ll see who we like.”

It might have taken a week for the editors to read rather than a weekend. But the week after that I had meetings with editors scheduled every day.

This was, perhaps—after eight years as an itinerant grad student, sending out writing and waiting months to receive boilerplate rejection slips—somewhat overwhelming. By the first meeting, at a well-respected independent house, an all-too-familiar seasick feeling was coming on, as the editor introduced me around. Somehow over the last few days, nearly everyone in the office had read the manuscript. An assistant told me she loved how the metropolis my novel was set on the slopes of a smoking volcano, how no one who lived there ever brought it up or seemed to care. She asked me if I’d ever been to Hawaii, where she was from. Everybody there seemed smart, energetic, likable, young. I tried to smile as they crowded around me, aware I wasn’t saying much, got through my goodbyes, and made it to the bathroom, where I shat blood, and managed not to throw up.

The following morning I was too sick to make the next meeting at all. I was staying for the summer in a rent-stabilized East Village sublet I’d found, narrow as a submarine. The regular occupant was a special ed teacher, an aspiring playwright and outsiderish painter of traumatic childhood events. His mammoth canvases stared down from the peeling plaster around his bed, captioned with black-painted script at the bottom. “And then June cut her leg” featured an overweight girl in a swimsuit with a bloody gash above her knee and a wide howling mouth. “Tommy liked to shoot rats from the porch” depicted a ramshackle house at night, and an adolescent boy in an undershirt, his rifle barrel aimed straight at the viewer. Lying there with June’s scream and Tommy’s reddened eye taking a bead on me, I thought about how long I’d been living for this break, some hateful inner voice telling me it had all been too good to be true.

My younger brother, who lived in the neighborhood, came over with some anti-nausea medicine and sat with me, improvising a visualization exercise to calm my mounting panic. The exercise helped, and the massive doses of steroids I’d begun taking were kicking in. With the ulcerative colitis episode subsiding, I was able to make the rest of the meetings.

I felt like I saw half of the city that week—the inner half—every door previously closed to me suddenly thrown wide, like I could walk into any office on the island and start shaking hands. I was an overnight connoisseur of tome-filled lobbies and plunging city views. Most of the editors I was meeting, like my agent, were young—my age, my generation, elated to be finding one of their own. Each of them seemed to feel the book was saying something they themselves had been struggling to express; I felt as if I’d been childhood friends with them all. The last editor, Bill told me, was going to be a little older, in his mid-forties, one of the great editors of the era, in fact. Bill rattled off a list of the man’s authors, several of whom were heroes of mine. But one thing I should know—he was battling cancer. Doing well, though, word was. The prognosis, thank God, was good.

By that last meeting on Friday, the steroids and I were fully in our usual honeymoon period—nausea banished, colon stunned out of attacking itself, energy cranked enough to bestow a calm unstoppability while not yet at the level of sleeplessness or vicious mood swings. Whatever remaining woozy unease I was feeling was banished by the sight of Robert Jones, who was so clearly sicker than me. Instead of making me wait in a lobby, he’d come down to meet me at the HarperCollins front desk, walking slightly stooped, his left arm held in protectively against himself.

“Excuse my pace,” he said, his tone somehow both deadpan and luxuriating in melodrama, “I recently had my left side removed.”

We shook hands and stepped outside so he could smoke a cigarette. In the course of our conversation, I asked about some of his more famous authors, expecting guarded and respectful replies, but he cut right to the juicy stuff, telling me how he practically had to move in with one author to help him get his book done, complaining how another refused to promote his books but would bend over backwards to hawk a movie version.

“I suppose these aren’t the kind of stories an editor should tell a young author whose novel he wants to acquire.” He regarded me merrily. “Don’t worry,” he said. “I’m not going to move in with you.”

I would have felt blessed to work with any of editors I’d met that week, but Robert was my first choice, and Bill’s as well. Robert, though, left nothing to chance. He was the highest bidder at auction, consenting to be turned upside-down and shaken for change. At day’s end, after Bill told me the final figure on the phone, I wandered numb out of the special ed teacher’s apartment and up St. Marks to the subway. I was having dinner with two of my closest friends from college, also aspiring writers, one of whom had been gifted by a grandparent a coupon good for two free entrees at a Ruth’s Chris steakhouse, our plan being to split the cost of the third. I couldn’t bring myself to tell them how much money I’d just made. I said it was a lot. Then I kind of laughed. Then I said it was a whole lot. There was an uncomfortable silence as we all realized I wasn’t going to get more specific.

I didn’t tell my brother. I didn’t tell my parents, whose average income wasn’t much more than mine, all of us feeling that weirdness, that new distance of me not telling them. Part of the purpose of a large advance, I understood, was to gain a book publicity. But I told nearly no one. Instead, for weeks, I did math in my head. I subtracted my agency’s cut and divided the figure by the five long years I’d lavished on the book and came out with a perfectly reasonable—boring, even—middle-class salary. I divided it by the ten years since college I’d been writing, the result more lackluster still. I thought of acquaintances and friends of friends who’d been riding the dotcom wave into stupefying wealth. I was basically a peasant, I reasoned. But one who could pay off his student loans. One in need of tax advice.

It was about a third of a million bucks.

2.

“Beautiful!”

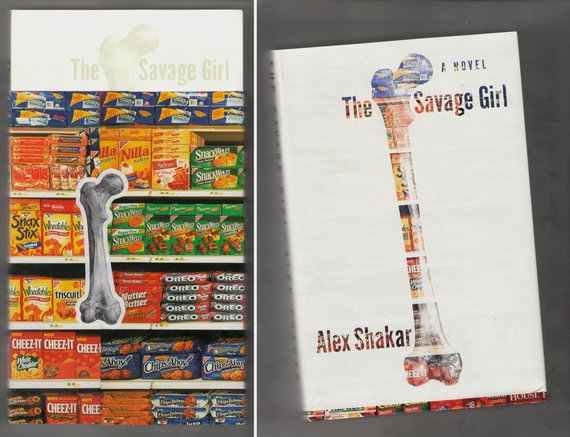

“The white background.”

“The bone made of products.”

“And the cover itself, beneath the jacket. So colorful.”

It was true. The hardcover book, hot off the presses, was a work of art. I could barely pry my eyes from it as the HarperCollins marketing and publicity teams passed it around the conference table.

“Without the jacket, it looks like a textbook.”

“Like a marketing textbook!”

This was true, too. Beneath the white jacket, the cover—front, back, and spine—was a single, glossy photograph of a supermarket shelf, brimming with snack foods.

“We should market it to marketing classes,” said a marketer, to laughter and general accord.

I’d been at first worried what the marketers might think of my novel, exploring, as it did, certain complex emotions with regard to consumerism. But they were proving to be among the book’s biggest champions. They’d read it with attention and care, told me how moving they’d found it, how relevant and what was more, timely. The Diet Water. The rainforest fashions. The feeling that all this gorgeous, crazy decadence was about to blow. The marketing director said that reaching the end of a chapter on her way to work she’d looked up to realize she’d missed her subway stop.

I had the sense that they, the marketers, had been working nearly as lovingly on the book over the last few months as I had been. While I’d been going through the rounds of edits and copyedits and proofreading, they’d come up with a postcard campaign and a press kit, and made sure the otherwise austere galleys came wrapped, like presents, in that colorful supermarket shelf. It was now the summer of 2001, and so much had changed. The Bush son had won the national election by a vote of 5-4. The NASDAQ lay in smoke and ashes. On the evening news, dotcom workers with designer nerd glasses and odd, lingering smirks could be seen walking out of bankrupted startups, boxes in hand.

But the city once more was sunny and mild, and we’d all survived. I’d turned 33, filed my first accountant-assisted tax return. And my editor Robert was back from the brink of death. He’d come through the chemo and radiation and had been promoted to editor-in-chief. He’d edited two seasons’ worth of manuscripts, including my own—with great insight and gusto and even joy, judging from his running commentary in the margins. He wasn’t here at the marketing meeting, but we’d been assured that he was fine, on vacation in California, soaking up the waves. It might have been hard to believe, had I not seen him the month before in Chicago at the Book Expo, in a slick gray suit and a yellow tie, hair fully regrown, slightly flushed but otherwise in top form. He’d latched my elbow and directed my gaze to a thin curl of a woman hunched in a corner of the HarperCollins reception, scribbling on a pad.

“Joyce Carol Oates,” he said. “One of my authors. She’s writing her next novel.”

“Here? At the party?”

“What are you smiling at?” he exclaimed. “Where’s your pad? What have you given me lately?”

That afternoon, I was sat behind a table, where I signed galleys for the occasional book collector (“Don’t make it out to anyone,” they instructed, annoyed. “Just sign and date.”) or fan of the more established writers drifting over from the long lines nearby. Two tables down, Clive Barker, in a silk shirt with the top four buttons undone and an iron cross hung from his neck, was calling for more tea.

“Do you know what ‘teabagging’ is?” he asked an elderly woman waiting in front of him with her open book, then proceeded to provide her an anatomically detailed explanation.

Barker was another of Robert’s authors, as was Ann Patchett. I met them both later that night, at a dinner Robert had scheduled for the four of us, along with my girlfriend, and Clive’s muscular husband, at the five-star, immodestly-named Everest, done up in faux-zebra-skin chairs and perilously shard-heavy chandeliers.

“My newest star,” was the way Robert introduced me, sprinkling pixie dust. “And his lovely girlfriend.”

“We’re going to party all night,” Barker announced, in his ravaged, British rock star voice.

Patchett, conversely, expressed consternation that the dinner had been scheduled for 9:30, saying she never went to sleep later than eleven. Robert shot me a mischievous smile.

We didn’t stay out all night, but afterward, out in the empty downtown street, Clive and I lingered, wishing each other luck on our upcoming tours.

“Don’t let them put you in second rate hotels,” he said. “They’ll try to do that sometimes. And make them fly you first class. They’ve got the money—they’ll pretend they don’t, but they do.”

He got into his waiting car. I waved as it pulled out. Over dinner, he’d talked about the undead-themed videogame he and Electronic Arts had just put out. I knew I wouldn’t be asking HarperCollins for airplane upgrades anytime soon. Nonetheless, I was honored, a little awed, too, by this advice, from a certified star to—could I allow myself to entertain the notion?—a rising one.

On the occasional visit to my parents back in Brooklyn, my father, an actor who’d had a too-brief brush with the big time when he was younger, had taken to commenting on the performances of celebrities on talk shows for my benefit: who looked natural, who stiff, whose posture was slumped, voice was crimped. Sharyn Rosenblum, my book’s vivacious, fire-haired, warrior-woman publicist, had been gauging my readiness as well. At the Expo, she’d put me in front of a reporter and watched with concern as I tried to explain my trendspotter-characters’ beliefs—how the culture was supersaturated with irony, how a strange, new, schizoid era of what they (and I) termed “postirony” was on the way—going into too much detail and well over soundbite-length. She’d taken me to a party in a sprawling hotel suite and introduced me to a Fresh Air producer, neglecting to tell either of us who the other was, and watched us stand there trying to figure out why we were shaking hands.

Now, back in New York after the marketing meeting, she steered me into her office, where she and her equally vivacious protégé, Claire, became my personal media trainers, boxing coaches in pumps, firing off interview-from-hell questions:

“Why is the book so dark?” Sharyn asked. “Aren’t you worried about getting too trendy yourself?” And then: “What do you think of all this promotion and packaging and hype surrounding your book?”

The two of them studied me as I fumbled through my responses.

“Don’t say ‘um,’ so much,” Sharyn said.

“Or ‘you know,’” Claire said.

“I don’t know,” Sharyn said. “You’ve got to tell me.”

“Don’t mumble,” Claire said.

“If you don’t know what to say,” Sharyn said, “stall by saying, ‘That’s a very good question.’”

“‘Wow,’” Claire demonstrated. “‘Great question!’”

“See? It’s flattering too.”

Sharyn took me to a couple more parties in downtown lofts and steered me around, but mainly she was working on getting me ink. She thought there was good chance People magazine would run a profile of me for their October issue, to coincide with my novel’s mid-September release. Meanwhile, Details wanted to do a photospread. The idea was that I would pose in various haute-couture outfits, which would then be tagged in the captions, listing designers and prices.

“So it would be . . . an advertisement?” I asked her.

“Alex,” she said. “They’re bumping Jimmy Carter to get you into the issue.”

I went on, for a minute or so, to question Sharyn about the wisdom of having the author of a trenchant novel about consumerism selling clothes in magazines. A week earlier, she’d come to me with a proposal from a major cigarette company to host parties for my book despite (or perhaps due to) a scene in it depicting a creepy rave sponsored by Camel. I’d politely nixed the cigarette deal, but it didn’t take much to convince me to do the photoshoot.

The Details team met me at a trendy, white-vinyl-upholstered East Village bar they’d leased out for the day. Except for the lighting guy, a droll ponytailed German who looked to be about my age, they were all disconcertingly young, mid-twenties at most. I got the feeling they were assistants and interns getting their shot at a shoot of their own. I’d been carefully growing out my hair, hoping to counteract the staidness of my hardcover photo, in which I’d hoped to look unpretentious but just looked angry and square. But comparing my actual face to the one on that same picture from the press kit, the hair stylist shook her head and set about re-trimming my hair. They then dressed me, for no reason I could fathom, in 80’s garb—a dark suit jacket and a striped polo shirt with the collar flipped.

“It’s a funny book, right?” said the photographer. “So you should smile really wide.”

I’d never done this with my face before. Then again, I’d never worn a polo shirt. I tried. The result seemed to unsettle her, but she went on, undaunted.

“And jump off that bench.” She pointed. “And throw out your arms and kick up your heels.”

Off I went. From their expressions, I could infer what my own must have looked like: like I was being stretched on a rack.

“Eighties Man,” the German sardonically pronounced.

The other event at an East Village bar that summer was a pre-launch party for the novel which Sharyn had arranged.

“Great news,” she said on the phone the morning thereof. “It got picked up in the Observer. They even ran an excerpt.”

It was the first piece of press the book had gotten. On my way to the party, I bought a copy:

How to market a book by a young Ivy League author whose prose thoroughly confuses you? Compare him to Thomas Pynchon, cross your fingers and hope for the best, baby!

This was followed by an out-of-context sentence from a sex scene. Followed in turn by some other party one could go to instead.

Stricken, feeling like I’d been molested, I threw the paper away, took deep breaths, and entered the bar. At every table, and spaced every three feet down the bartop, lay photocopies of the article. A few early guests were perusing it. Sharyn came up to me, a whole stack of them in hand.

“Did you see it yet?” she asked.

“Did you? Did you read it?”

“So it’s a little snarky. They’re like that with everyone.” As my parents came through the door, she stuck copies into their hands.

I made a few small, wince-worthy blunders at the party, and spent too much time trying to impress a group of postcollegiate interns at Charlie Rose who were clearly just there for the free drinks. But it served its purpose, and Sharyn seemed happy with how it went. People was indeed going to run the profile. More good news followed, as the early reviews showed up in the trades—all of them glowing. It was really happening. Faced with the evidence, even that cynical little inner voice was finally starting to quiet.

The only dark spot was that Robert was back in the hospital. We were all told that it was just a minor setback and not to worry. Worried anyhow, I went to visit him. I’d been preparing myself, but the sight of him shocked me. He smiled, nervously. For the first time since I’d known him, he was at a loss for words.

“So how’s that vacation going?” I said.

He laughed, smile easing. “It was splendid up until two days ago.”

He’d been on a California beach, he went on to tell me, wading into the waves, when his lungs had begun filling with fluid.

To make up for his foreshortened vacation, we now took turns extolling the vaguely aquatic theme of the room, cataloging everything from the peaceful East River view to the aquamarine hue of the visitors’ couch to the waterworks of the lung machine itself, which, as we spoke, was sucking reddish liquid from his chest through a long plastic tube and into a burbling plastic tank at the foot of the bed. The lung problem, he said, was correctable by surgery. There was a chance it wouldn’t work, he admitted, and his eyes shone as he said it, but he’d come through worse. I asked if he had family coming, and he said he’d ordered his mother not to, figuring he’d be out of the hospital by the time she would have gotten here; and that besides, he had his authors to keep him entertained.

“So entertain me.” He made a gesture like asking a waiter for the check. “Write something!”

3.

Robert’s memorial service was held on September 10, 2001, eight days before my novel’s release. It was a star-studded, though brief, affair in the auditorium of a midtown social club. Afterward, Bill and I retreated to a low-key restaurant, Bill talking loudly about how fake the whole thing had been, how disgusted Robert himself would have been. Bill was outdrinking me but even so I was surprised how quickly he’d gotten drunk. He went to the bathroom for the second time and I ordered another drink, hoping to catch up. I almost wished, that afternoon, I could have been outraged over the loss of Robert, too, but really all I could feel was gushing gratitude, for having had the brief chance to have been the man’s friend, for the whole HarperCollins juggernaut he’d marshaled on my book’s behalf, for the simple fact that here I was, hanging out with my savvy, preppie friend and agent a week before my first novel’s release. It would be a long time before I’d learn that in the bathroom Bill was calling his dealer, arranging a buy; that when he hurriedly paid and left, it would be to smoke crack all night; that he’d keep right on using, and disintegrating, from there.

The next morning I was getting ready to leave my parents’ apartment in Brooklyn for the airport when my father turned on the radio. We climbed the fire escape to the roof and watched the first tower burn. A cloud of white pages had fluttered all the way across the river and overhead. I thought they might be messages from the terrorists, but when my father caught one, it was just legalese. Fearing the possibility of chemical weapons, we went back downstairs and watched the rest of the catastrophe on cable TV. With the first collapse, amid the senseless snuffing of all those lives and all the rest of the sickening loss, I registered a faint pop within, as everything I’d been filling my head with this last, banner year snapped away like an idle minute’s daydream.

“There goes your novel,” my father said, in a dry little voice I recognized anew.

I watched the second one fall, then went and lay down. My very loss was meaningless compared to those who’d lost for real. Then I went out and walked around, trying to volunteer for something like everyone else.

No sooner were the politicians and pundits and media makers back at their posts than they were retooling for the grim new era. Roger Rosenblatt and Graydon Carter proclaimed “the end of irony,” and good riddance. President Bush and Mayor Giuliani exhorted citizens to patriotic acts of shopping. Flag-filled, “keep America rolling” commercials for cars and pickup trucks began rolling out over the airwaves. Few were in the mood for certain complex emotions with regard to consumerism, as felt by a group of fictional trendspotters making the best of their glittering, supercool, doomed little world.

A couple of reviews, over the coming weeks, deemed the book prophetic, though more didn’t fail to mention its unfortunate untimeliness, and even some of the raves read more like obituaries (“a sharply observant relic of the recent past”). I toured the country, observed by my fellow plane passengers with suspicion and occasionally returning the sentiment. Here and there bookstores offered a modest turnout; many were empty. In Seattle, I read with the writer Rabih Alameddine, who’d been having a far worse time than me in the airports, and whose tour after that night was being canceled altogether. HarperCollins, in my case, cut its losses and pulled the second advertising round it had planned. People magazine pulled my profile, because of its mention of a bomb scene in the novel, which they felt, under the present circumstances, might offend sensitive readers. The Details photospread (mercifully, in this case) was reduced to a single page, a few lines about me and the novel running over a picture of the top half of my head, my eyes peeking over the bottom of the page—no 80s garb visible at all.

There were no national television appearances, but through sheer tenacity, Sharyn got me a couple of local cable spots in New Jersey and Connecticut, and I was determined to make her proud. I rode alone in a car service to the latter, a daytime talk show in a sound studio out in the middle of an industrial park, and waited to go on in a small green room with an Asian-American girl who played the cello. They called me up to the stage and sat me down with the host and hostess, their faces caked with makeup, which I found amusing until I looked up at the monitor and saw that onscreen they seemed rosily healthful, whereas I, sans makeup, looked either like I was bound for the crypt or had just risen from one. With only seconds to go before we went live, the hostess turned to me and said her first question was going to be what I had to say to people who were saying my novel was irrelevant.

I gave her my most winning smile. “How about a different first question?”

(All images courtesy the author)