1.

What if the best thing art has to offer is freedom from choice?

There’s a reason it’s high praise, not criticism, to say that a film or a piece of music or a good novel “sweeps you along.” There’s a selflessness in it: not just the pleasure in pausing the parts of the brain that plan and calculate and select, but in the temporary surrender of investing in someone else’s choices. Good art can be where we go for humility: when we’re encouraged to treat each of our thoughts as worthy of being made public, it can be almost counter-cultural to admit, in the act of being swept along, that someone else is simply better at arranging the keys of a song or the twists of a book and making them look like fate.

Freedom from choice is a seductive way of thinking about art—and it’s at the heart of the debate over the cultural value of video games. Video games, for their cultural boosters, promise an art based on choice: an interactive art, possibly the first ever. For their detractors, “interactive art” is a contradiction in terms. Critics can point to video games’ narrative clichés or sloppy dialogue or a faith in violence as the answer to everything; but at base, they seem to be bothered by the idea of an art form that can be “played.” Choice is their bright line.

Last spring, Roger Ebert nominated himself to hold that bright line on his blog. And though the 4,799 comments (to date) on his original post weighed in overwhelmingly against his claim that “Video games can never be art,” and encouraged him to back off of that blanket assertion, he summed up as eloquently as anyone the danger posed to narrative by video games’ possibility of limitless choice:

If you can go through “every emotional journey available,” doesn’t that devalue each and every one of them? Art seeks to lead you to an inevitable conclusion, not a smorgasbord of choices. If next time I have Romeo and Juliet go through the story naked and standing on their hands, would that be way cool, or what?

It’s possible, as Owen Good did, to write off the whole argument as empty, just a chest-thumping proxy war between generations or subcultures: “Art is fundamentally built on the subjective: inspiration, interpretation and appraisal. To me that underlines the pointlessness of the current debate for or against video games as art….Is there some validation the games community seeks but isn’t getting right now?”

But then, every argument about art is about validation, about the assignment of prestige—yet those arguments are still worth having, because they can also be about something else. The argument over video games is about finding a place for choice in art, about respectability, and about empathy. And the best way into that argument may come from considering another cultural practice’s struggle for respect in its early days. I think that there’s already been a powerful interactive art, one that has some lessons for video games: psychoanalysis.

2.

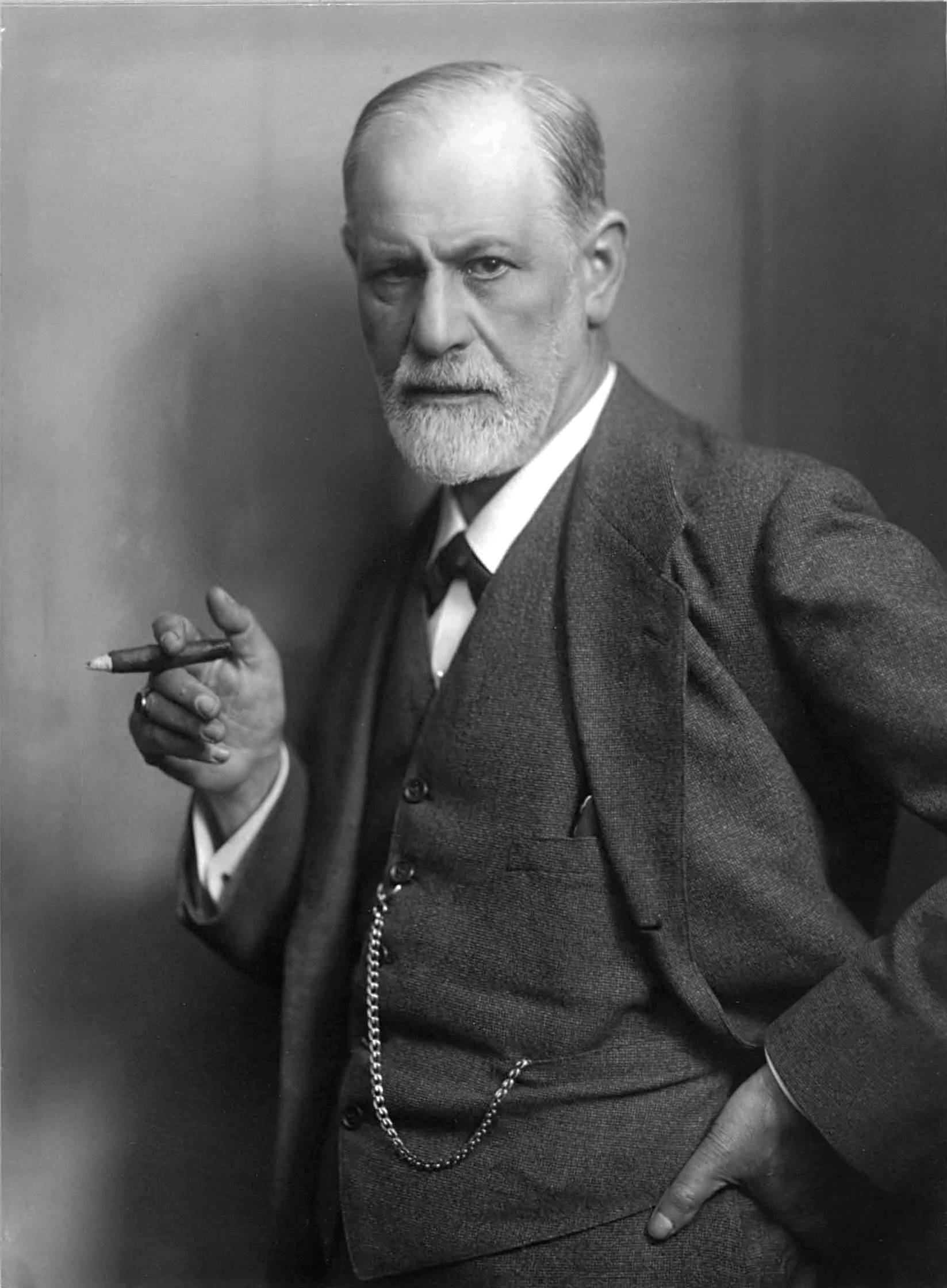

Too Jewish, too sex-obsessed, too much a cult of personality centered on Freud: before it was a more-or-less respected science, psychoanalysis was widely thought to be all of those things. George Makari’s Revolution in Mind begins the history of the movement that gathered around Sigmund Freud with a clique small enough to fit into a Vienna living room. Freud dreamed of creating a new scientific discipline, one legitimized by university departments, teaching hospitals, international conferences, and state funding; but he couldn’t even secure agreement among the rival scientists, doctors, artists, writers, liberal activists, and sexual libertines all drawn, all for reasons of their own, to his ideas of the unconscious. What exactly was this movement? Was it a school of medicine, a philosophical circle, a budding political party? With its objects of study so hard to pin down objectively, it was hard to say with certainty.

Too Jewish, too sex-obsessed, too much a cult of personality centered on Freud: before it was a more-or-less respected science, psychoanalysis was widely thought to be all of those things. George Makari’s Revolution in Mind begins the history of the movement that gathered around Sigmund Freud with a clique small enough to fit into a Vienna living room. Freud dreamed of creating a new scientific discipline, one legitimized by university departments, teaching hospitals, international conferences, and state funding; but he couldn’t even secure agreement among the rival scientists, doctors, artists, writers, liberal activists, and sexual libertines all drawn, all for reasons of their own, to his ideas of the unconscious. What exactly was this movement? Was it a school of medicine, a philosophical circle, a budding political party? With its objects of study so hard to pin down objectively, it was hard to say with certainty.

Maybe it was art. That, at times, was the opinion of James Strachey, one of the more important figures in legitimizing this strange discipline and winning it an international reputation. James was the brother of the Bloomsbury author Lytton Strachey and a scholar of Mozart, Haydn, and Wagner; he was also one of the first English-speaking psychoanalysts and Freud’s most important translator. It’s because of Strachey that we still use Latin terms like id, ego, and superego, rather than Freud’s more down-to-earth “the It,” “the I,” and “the Over-I” (as a literal translation of his German would have had it).

As an aspiring “talk therapist” in 1920, Strachey came from London to Vienna to undergo an extensive training analysis with Freud. He wrote to Lytton that he divided his time equally between the doctor’s office and the opera house—and, intriguingly, he described his sessions as a brand-new kind of aesthetic experience, a kind of private opera in which the therapist was the director and he was the star. Here is what he wrote after 34 hours on the couch:

[Freud] himself is most affable and as an artistic performer dazzling…Almost every hour is made into an organic aesthetic whole. Sometimes the dramatic effect is absolutely shattering. During the early part of the hour, all is vague—a dark hint here, a mystery there—; then it gradually seems to get thicker; you feel dreadful things going on inside you, and can’t make out what they could possibly be; then he begins to give you a slight lead; you suddenly get a clear glimpse of one thing; then you see another; at last a whole series of lights break in on you; he asks you one more question; you give a last reply—and as the whole truth dawns on you the Professor rises, crosses the room to the electric bell, and shows you out the door.

Why was the experience so aesthetically powerful, so unlike anything Strachey had seen before? In large part, it seems, the difference was that he was a participant in the drama, not merely a spectator—or maybe a participant and a spectator at the same time. There was a story being played out in one-hour increments; but the story was his story. His choices—how to react to each question, what to reveal and what to conceal, how to make sense of and advance the unfolding “plot”—gave the story its shape. And the scene of the real action was internal: “dreadful things going on inside you.”

At the same time, though, Strachey realized that this was not a simple exercise in introspection or an outpouring of emotions—it was a guided drama. Freud shaped it as much as his patient did, not by telling a story, but by skillfully arranging a limited number of choices, on the fly, that reliably delivered his patient to the sensation of dawning truth and artistic completion. What’s remarkable is that he did it with such consistency. Strachey wrote about a series of conversations, and yet they all seemed to shape themselves into a classical dramatic arc: premonitions, a mounting pursuit, a crashing climax, and a cliffhanger ending.

It’s true that James Strachey, aesthete as he was, brought his own unique preconceptions to Freud’s couch. But it’s also true that the dynamic he identified—the tension between free response and prearranged structure in each session—would, according to Makari’s history, be the cause of some of the growing movement’s greatest schisms.

For instance, Freud’s Hungarian disciple Sándor Ferenczi came to advocate “active therapy”: confronting patients directly, turning their answers back on them, setting deadlines for progress, enforcing sexual abstinence, and even, in one case, regulating the patient’s posture during sessions. On the other pole, the Frankfurt analyst Karl Landauer argued for a passive technique that teased out the patient’s resistances to treatment, insisting that the therapist must not “impose actively upon [the patient] one’s own wishes, one’s own associations, one’s own self.” Long after Freud’s movement had achieved the legitimacy he always sought, this tension between hands-on and hands-off treatment would end friendships, partnerships, and careers.

3.

Of course, video games are not a kind of psychoanalysis, and psychoanalysis would not make much of a video game (“press ‘A’ to confess sexual feelings for Mother”). Nor has psychoanalysis shaken off its detractors, then or now, by painting itself as an art; as compelling as Strachey’s vision was, there was always more prestige in claiming the objectivity of science. Besides, if it was so pleasurable for Strachey to reflect on his treatment, how serious could his problems have been?

Strachey may have idealized his treatment—but he also found the emotional potential in a practice that many of his contemporaries were writing off as a fad. And in doing so, he gave evocative evidence for the possibilities of interactive art. He also, unwittingly, described the reasons why video games seem so promising to so many. They can be an art that makes us both spectators and performers, one that can turn us from passive audience members to partners, flattening the relationship between artist and audience without erasing it altogether. In the private drama he co-created, Strachey was decidedly the junior partner; Freud was such an effective senior partner because he balanced choice with structure, keeping his patient personally invested even as the session stayed fastened to some important dramatic rules. Is it too far a stretch to see this as a type for the relationship between a skilled video game designer and a savvy player?

In video games, our story can be anyone’s but our own. But their greatest promise, and greatest advantage over traditional art, is in their power to create empathy—to make someone else’s story feel like our own because we are temporarily living it. We’ve been able to lose ourselves in video game characters ever since the first player sent his Italian plumber off of a ledge and exclaimed “I died!”—not “Mario died!” Today, though, that power of empathy is being put to much more complex uses. In Slate’s annual Gaming Club discussion last month, Chris Suellentrop reflected on “the scene—it feels unfair to call it a level” in the game Heavy Rain that forced him to cut off his own character’s finger: “It felt agonizing, like I was cutting off my own finger. It was one of the most remarkable things I’ve ever experienced, in video games or any other medium.”

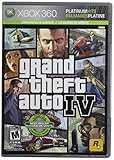

Similarly, in Extra Lives—both a defense and a criticism of video games’ cultural potential—Tom Bissell spends pages meditating on a drive through the night city in Grand Theft Auto IV, with two bodies hidden in the trunk of his car. It was a dangerous risk undertaken to advance his character’s underworld career—and it was also an unsettling choice in which he felt criminally complicit. Interactivity, Bissell writes, “turns narrative into an active experience, which film is simply unable to do in the same way.” Film could not have left him with the same sense of guilt.

Similarly, in Extra Lives—both a defense and a criticism of video games’ cultural potential—Tom Bissell spends pages meditating on a drive through the night city in Grand Theft Auto IV, with two bodies hidden in the trunk of his car. It was a dangerous risk undertaken to advance his character’s underworld career—and it was also an unsettling choice in which he felt criminally complicit. Interactivity, Bissell writes, “turns narrative into an active experience, which film is simply unable to do in the same way.” Film could not have left him with the same sense of guilt.

It might be that empathetic power that ultimately brings the argument over video games’ cultural value to an end. Even in the midst of his criticism, Ebert concludes that the works of art that have moved him most deeply “had one thing in common: Through them I was able to learn more about the experiences, thoughts and feelings of other people. My empathy was engaged.”

Perhaps there aren’t any games that engage his empathy, let alone engage it more powerfully than a film. Maybe there never will be: it’s telling that the moments identified by Bissell and Suellentrop as emblematic of video games’ potential tend to revolve around extreme violence. Even Bissell complains that game designers tend to give short shrift to narrative and characterization and line-by-line prose—and maybe we shouldn’t expect that to change. Given the amount of capital most sophisticated games demand—let alone the capital it would take to finance one complex enough to count as truly interactive—maybe we should expect them to settle permanently into the niche of the summer blockbuster.

But even among the big-budget films, there are those that challenge us and move us. Video games, in principle, don’t have to be any different—and the potentially interactive art they hold out promises to move us with the intensity of Strachey’s light breaking in. When and if that happens, we shouldn’t expect art to be washed away in a flood of endless choices, with characters going through the story “naked and standing on their hands.” The most interesting argument won’t be about video games’ status as art, but about how to build an art that most effectively balances choice and structure, openness and narrative. Every increment toward freedom could mean deeper involvement and deeper empathy, at the cost of shapelessness; every increment toward structure could mean more captivating stories and characters—even as we find it harder to imagine ourselves into their shoes. The debate between the virtues of freedom and control, articulated almost a century ago by Freud’s disciples, will play out again, inconclusively, in a realm they could have barely imagined.