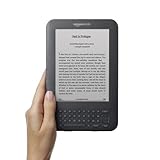

In a new commercial for the Amazon Kindle, a man and a woman lie on beach chairs, glazing beneath the sun. The tragically average man is trying to read his iPad; due to the glare, he can no longer follow his Patterson. The woman, Kindle in hand, has no problem with the sun; by the looks of her, she has no problems at all. The man’s shortcomings are plain, and the message is equally clear: the Kindle will make you sexier and resist the sun.

In a new commercial for the Amazon Kindle, a man and a woman lie on beach chairs, glazing beneath the sun. The tragically average man is trying to read his iPad; due to the glare, he can no longer follow his Patterson. The woman, Kindle in hand, has no problem with the sun; by the looks of her, she has no problems at all. The man’s shortcomings are plain, and the message is equally clear: the Kindle will make you sexier and resist the sun.

I find the ad faintly comical. In an effort to fend off Apple—which builds sex straight into its products—Amazon is grasping at whatever straw lies near. But for me, the fun ends there. After years of rising dread—the prophesied End of Books, the Bezos Newsweek cover—“it” is finally here. No longer are books being pitted against pixels; pointing out that paper isn’t reflective either seems very 2007. The war is now between tablets, as if the book never existed at all.

In recent years, grief for such losses—music stores, newsrooms, this tradition or that—has become so common and compressed that it’s become a cultural given. We now swallow our objections, lest they later seem absurd. A few years ago, I stood in Tower Records, praising its stock to a friend: You can hold a compact disc; buying an album is a genuine act. And just look at Bitches Brew: don’t you want to have it?

In recent years, grief for such losses—music stores, newsrooms, this tradition or that—has become so common and compressed that it’s become a cultural given. We now swallow our objections, lest they later seem absurd. A few years ago, I stood in Tower Records, praising its stock to a friend: You can hold a compact disc; buying an album is a genuine act. And just look at Bitches Brew: don’t you want to have it?

Of course, that Tower Records—along with most of its kind—is gone now; a jazz Pandora station is playing as I write. The transition was far less wrenching than I’d previously expected; in fact, there was really no pain at all. While I may miss aimless browsing, thoughts consumed by music, the process now seems needless, like baking bread from scratch.

I might say we’re at a moment when we face this choice as readers—the decision to climb into the boat or stay on familiar shores. But the decision is not truly ours. Time and again, these choices are made for us, by a collective sweep and push. One day, everyone holds an iPod, and the next day, so do you. Those who resist—the pipe smokers and vinyl hounds, stubborn to the end—come to seem affected, or possibly insane. The rest of us seem modern, and eventually commonplace.

The prospect of our wonders used to bring excitement. In the early nineties, after seeing Dick Tracy, I dreamed of his two-way radio. How cool would that be? I thought. Incredibly, I found out: as two-way radios came to market, then gripped every inch of our lives, they became not cool at all. Awe gave way to grabbiness: digitize everything, please. Books are the latest items to be forced into the hole.

The prospect of our wonders used to bring excitement. In the early nineties, after seeing Dick Tracy, I dreamed of his two-way radio. How cool would that be? I thought. Incredibly, I found out: as two-way radios came to market, then gripped every inch of our lives, they became not cool at all. Awe gave way to grabbiness: digitize everything, please. Books are the latest items to be forced into the hole.

So I should probably shrug at progress and enjoy a digital Roth. But—and at this stage, I know the pointlessness of saying it—books feel different to me. Everywhere I’ve lived, they’ve surrounded me; nearly every night since childhood, I’ve held one in my hands. My mother was a librarian; my father sat me on his lap and read Tom Sawyer aloud. I now do the same with my son, though he isn’t quite ready for Twain. Everyone, to some degree, has a variation of this history.

So here is the dilemma: you love your books, with their meaning and their warmth, but you’re not some weepy sap. You find romance in the object, yet none in being an outlier, unreasonably clinging to relics. Do you get on the boat—with its gorgeous women and glare-free screens—or ignore it and hold on? Had I asked myself this question around the time of my Tower trip, I would have flared out my response: I’ll never switch, you Logan’s Run drone. Books are too vital to trade for some overmarketed whim.

But in the time since, I’ve given myself over to plenty of similar whims—and against all odds, they haven’t ravaged my soul. Electric books hold no appeal to me; they feel like viral death. But so did music taken from a set of coiled wires. The sounds were what was important. So my answer now, however reluctant, is this: I’ll hold on to books for as long as I can. I’ll read them, lend them, fall asleep with them. I’ll hope they hold their own, that novelty will wane. And if it doesn’t—when it doesn’t—I’ll find myself among a crowd that I’d never hoped to join.

(Image: circuit board, from botheredbybees’s photostream)