After Sakincali Piyade I embarked on my Chicago trip and returned to The Fortress of Solitude, which I finished during the journey. Next was In Cold Blood by Truman Capote, which I had been meaning to read for a long time. The release of Capote with Phillip Seymour Hoffman rekindled my desire to read In Cold Blood, as I did not want to see the movie prior to reading the book. So, I dove into the gruesome story of the Clutter family murder in Holcomb, Kansas, in 1959. Capote divided In Cold Blood to three sections and created two parallel storylines, both of which make his narrative very fluid, factual and captivating. Given that in our time we have been witnesses to more outbursts of seemingly aimless violence than previous generations (Red Lake High School, Columbine), In Cold Blood does not come across as shocking as it might have when the Clutter murders took place and when the book was published in 1965. The unfolding events also show that the Clutters were not murdered by a random psychopath, rather by two ex-cons, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock, who were motivated to rob the estate. The murders described in In Cold Blood may not surprise the modern reader but Capote’s masterful chronicling of the events and extensive research that leads to the psyche of the Clutters, Perry Smith, Dick Hickock, investigator Alvin Dewey and the characters surrounding the murder arouses a sense of real familiarity with the events and leaves the reader wondering why the world works the way it does. I found myself wondering why the outstanding citizens, as exemplified in Herb Clutter’s honesty and dedication to society and Nancy Clutter’s impeccable record as a student and as a role model to all the young girls of Holcomb, always seem to be victim to society’s ills. I also thought about delusional and broken men such as Hickock and Smith: two men who had troubled childhoods, had been in and out of jail, tried to – and succeeded at times – to make an honest living, but always relapsed and turned to wicked means, the most disturbing of which resulted in the Clutter murder. I enjoyed In Cold Blood immensely, not because the story is particularly interesting or fresh, but because of the insightful details that Capote presents and the issues it brings up with regards to society and life.

After Sakincali Piyade I embarked on my Chicago trip and returned to The Fortress of Solitude, which I finished during the journey. Next was In Cold Blood by Truman Capote, which I had been meaning to read for a long time. The release of Capote with Phillip Seymour Hoffman rekindled my desire to read In Cold Blood, as I did not want to see the movie prior to reading the book. So, I dove into the gruesome story of the Clutter family murder in Holcomb, Kansas, in 1959. Capote divided In Cold Blood to three sections and created two parallel storylines, both of which make his narrative very fluid, factual and captivating. Given that in our time we have been witnesses to more outbursts of seemingly aimless violence than previous generations (Red Lake High School, Columbine), In Cold Blood does not come across as shocking as it might have when the Clutter murders took place and when the book was published in 1965. The unfolding events also show that the Clutters were not murdered by a random psychopath, rather by two ex-cons, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock, who were motivated to rob the estate. The murders described in In Cold Blood may not surprise the modern reader but Capote’s masterful chronicling of the events and extensive research that leads to the psyche of the Clutters, Perry Smith, Dick Hickock, investigator Alvin Dewey and the characters surrounding the murder arouses a sense of real familiarity with the events and leaves the reader wondering why the world works the way it does. I found myself wondering why the outstanding citizens, as exemplified in Herb Clutter’s honesty and dedication to society and Nancy Clutter’s impeccable record as a student and as a role model to all the young girls of Holcomb, always seem to be victim to society’s ills. I also thought about delusional and broken men such as Hickock and Smith: two men who had troubled childhoods, had been in and out of jail, tried to – and succeeded at times – to make an honest living, but always relapsed and turned to wicked means, the most disturbing of which resulted in the Clutter murder. I enjoyed In Cold Blood immensely, not because the story is particularly interesting or fresh, but because of the insightful details that Capote presents and the issues it brings up with regards to society and life.

After In Cold Blood I read nothing but The Economist and other news outlets for two months. I really enjoy reading The Economist and it is my favorite news publication, but two months of not reading any literature made me sad. When I last visited my friend John he asked me what I was reading and I told him nothing at the moment, implying that I was looking for a book that would drag me back to the wonderful world of literature. His suggestion was Motherless Brooklyn by Jonathan Lethem. Since I was so impressed by The Fortress of Solitude, another recommendation from John, I started the novel right away and, as had happened with Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, could not put the book down, even at the expense of sleep. Lionel Essrog is the main character of Motherless Brooklyn and suffers from Tourette’s syndrome (that’s when you cannot control what your saying and your mouth/brain spurts out profanities or meaningless words at random, mostly when you are under stress/strain). The title works magnificently to describe Lionel and his three friends from St. Vincent’s Orphanage in Brooklyn: Tony, Danny and Gilbert. The motley four work for Frank Minna, a shady small time mobster whose murder at the outset of the novel sets off the chain of events. The demise of Minna is dramatic for each individual as he was more than an employer to them: a father figure to Lionel and Gilbert, a role-model/rival for Tony and a comforting personage for Danny. Immediately after Minna’s murder Lionel and Tony get on the case to find the killers, but it soon appears that whereas Lionel is sincere in his desire to find the suspects, Tony has other motives. Lethem takes you through a fast two days through Lionel’s eyes, prompting Tourette’s in you, embedding tics in your mind and causing you to read compulsively to reach a resolution. The mystery is intricate yet Lethem drops hints all along for the careful reader to decipher the plot. But if you get carried away with Lionel’s Tourette’s (as I did) chances are that you will be as oblivious, yet simultaneously, surprisingly and equally alert, to everything that unfolds. The ending will, nevertheless, put a smile on your face.

After In Cold Blood I read nothing but The Economist and other news outlets for two months. I really enjoy reading The Economist and it is my favorite news publication, but two months of not reading any literature made me sad. When I last visited my friend John he asked me what I was reading and I told him nothing at the moment, implying that I was looking for a book that would drag me back to the wonderful world of literature. His suggestion was Motherless Brooklyn by Jonathan Lethem. Since I was so impressed by The Fortress of Solitude, another recommendation from John, I started the novel right away and, as had happened with Jonathan Franzen’s The Corrections, could not put the book down, even at the expense of sleep. Lionel Essrog is the main character of Motherless Brooklyn and suffers from Tourette’s syndrome (that’s when you cannot control what your saying and your mouth/brain spurts out profanities or meaningless words at random, mostly when you are under stress/strain). The title works magnificently to describe Lionel and his three friends from St. Vincent’s Orphanage in Brooklyn: Tony, Danny and Gilbert. The motley four work for Frank Minna, a shady small time mobster whose murder at the outset of the novel sets off the chain of events. The demise of Minna is dramatic for each individual as he was more than an employer to them: a father figure to Lionel and Gilbert, a role-model/rival for Tony and a comforting personage for Danny. Immediately after Minna’s murder Lionel and Tony get on the case to find the killers, but it soon appears that whereas Lionel is sincere in his desire to find the suspects, Tony has other motives. Lethem takes you through a fast two days through Lionel’s eyes, prompting Tourette’s in you, embedding tics in your mind and causing you to read compulsively to reach a resolution. The mystery is intricate yet Lethem drops hints all along for the careful reader to decipher the plot. But if you get carried away with Lionel’s Tourette’s (as I did) chances are that you will be as oblivious, yet simultaneously, surprisingly and equally alert, to everything that unfolds. The ending will, nevertheless, put a smile on your face.

If Motherless Brooklyn put a smile on my face in the end, Anneannem (My Grandmother) by Fethiye Cetin did the exact opposite. A good balance I might add. Lethem had me in 5th gear by the time I finished Motherless Brooklyn and I picked up Anneannem, which my friend Ela had brought me from Turkey and urged me to read, for a light read. The memoirs that Cetin relates are a mere 116 pages and I figured it would be a good transitional book between Lethem to Dostoyevsky. I started reading Anneannem on Sunday morning and Cetin’s style, as well as the romantic light under which she presented her story, captivated me. I took a break a quarter of the way through and went outside to enjoy the day. I called one of my grandmas on my way to the movie theater, just to hear her voice and rejoice in her presence. When I went to bed at night I picked up Anneannem and it kept me up until 3, crying, thinking and feeling emotions that were left alone for a long time. Cetin’s grandmother was an Armenian separated from her family during the Turkish deportation of Armenians in World War I. She was brought up by a Turkish family in Maden, Elazig in Eastern Turkey. She and the seven other girls that were separated from their families at the same time managed to preserve their heritage despite being converted to Islam and marrying Turks. Cetin grew up in her grandmother’s house, when, after her father’s unexpected and early death, her family moved in with the grandparents. It was, however, not until very late that Cetin learned about her grandmother’s past and, in the process, became one of her sole confidantes regarding the hardships she lived through. As Cetin relates her grandmother’s story, she also tells the reader of her own frustrations, embarrassment and disillusionment with the official Turkish line regarding the Armenian deportation. Horanus Gadarian’s story is heart wrenching, it makes one wonder how people can cause such pain on their neighbors, their fellow countrymen or, simply, to each other. Horanus’s wisdom and love for not only her family but towards all who sought her company is awe-inspiring. Cetin manages to trace Horanus’s family in the United States and tells the story of a very touching reunion after her grandmother’s death. Anneannem is a captivating little book that in the space of a 116 pages tickled my own pleasant memories and admiration of my grandparents, had me thinking about the cruelties that humans suffer in each others’ hands and the beautiful Armenian culture that Turkish officials did their best to destroy. Finally, Anneannem impressed me for its candid and lovely storyline. Unfortunately, Anneannem too is only available in Turkish.

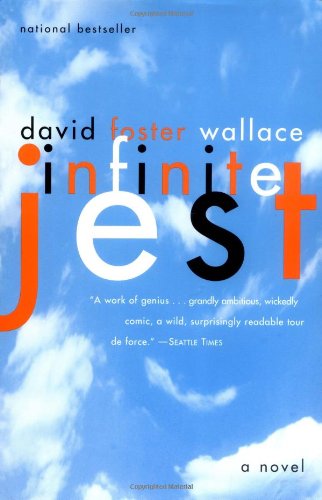

I have just begun my first Russian novel, Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Wish me luck, I probably won’t be writing again for a while, especially because I intend to read David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest after this one. Of course, all of this planning is subject to change on impulse. Good luck and good reads everyone, cheers!

(So, that’s all from Emre for a little while. Thanks, Emre! — Max)

Part 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Emre’s previous reading journal